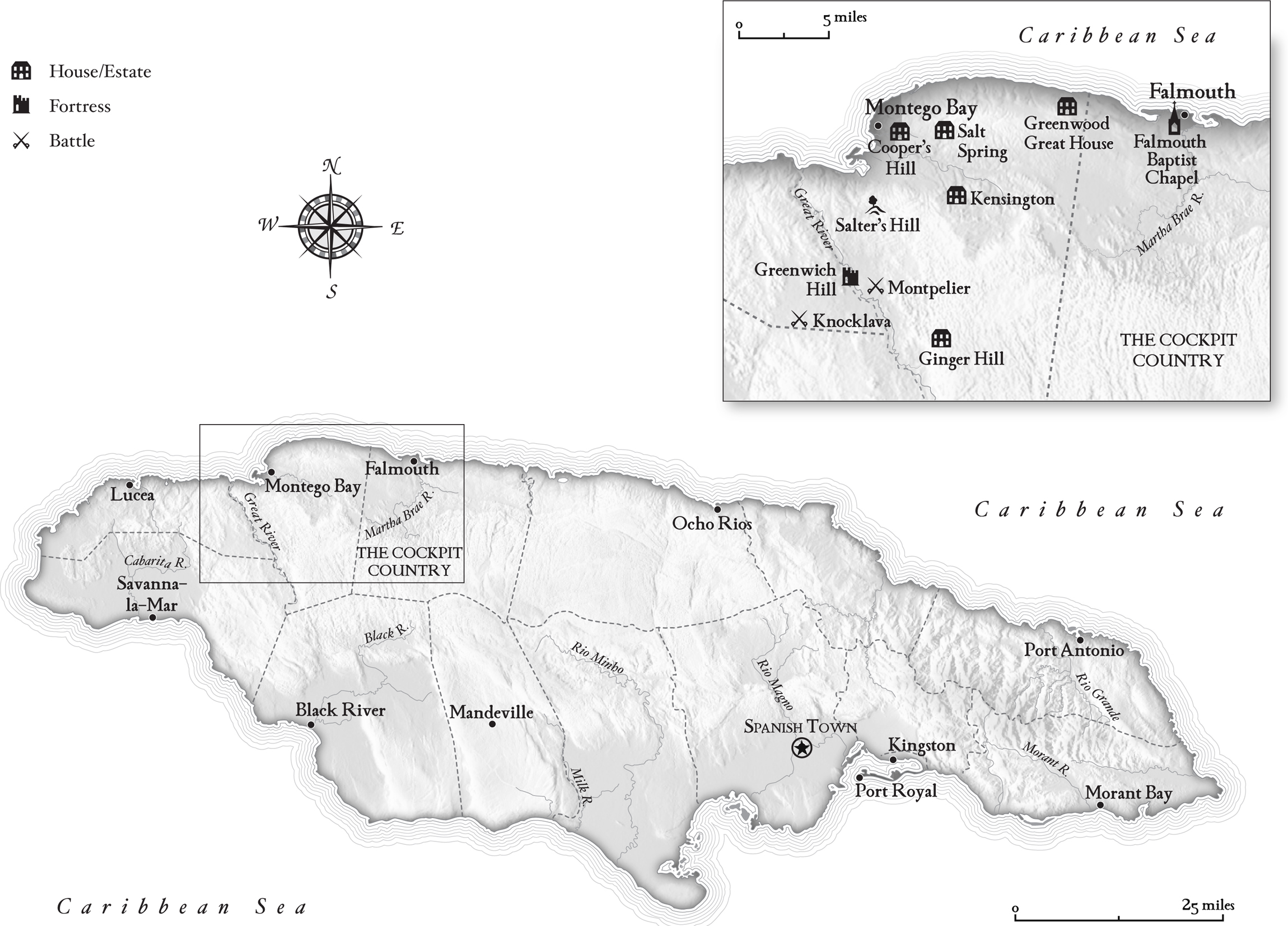

ON THE NIGHT OF DECEMBER 27, 1831, a watchman standing on top of the courthouse in the Jamaican city of Montego Bay spotted a fire on a hillside south of town. Then another fire appeared close by. And then another.

The meaning of this chain of fire was instantly clear to the watchman, Colonel George Lawson, who had beenlike the rest of his militia unitin a state of high alert because of credible evidence that the slave population of the northwest shore of Jamaica was about to rise up in revolt.

Lawson reported the fires to John Roby, the collector of customs at the port, who had almost certainly already seen them. As the Caribbean night sky gradually turned the color of copper, Roby wrote an urgent message to the governor of Jamaica underlining two words, a gesture almost never seen in official correspondence:

Sir, I consider it my duty to inform you that there is at this moment a serious fire raging in a southeasterly direction from this town, apparently 8 or 10 miles distant, and it is supposed at Hampton Estate but from the glare I fear it extends to other estates in its vicinity lying more to the southward. From the late insubordination of the negroes on many estates in the neighborhood, which has caused the militia to be under arms since Sunday last, it is feared that this fire is not from accidental causes and I beg the favor of your giving his Excellency the governor immediate information thereof.

He then added a postscript, knowing that one company of a badly trained militia would not be sufficient to prevent the white population from being massacred:

past 9

I have just been informed that Kensington pen and Mr. Tullocks settlement have been burnedwe have one company of the 22nd regiment in this town.

Lawson and Roby had no way of knowing if the family had been left alive or not. By ten oclock, the men had counted at least six fires that seemed to blend into a terrifying orange crown on the hills. By this point, Lawson feared the east part of the parish would be destroyed by morning. If anything, this was an underestimation. Fires were breaking out all over northwestern Jamaica.

One man on a plantation in Cornwall started a letter and kept revising it throughout the night:

The work of destruction has commenced. We now see two fires, evidently in the direction of St. James.

Ten oclockWe have just received intelligence that the fire at Palmyra estate was extinguished, after burning down one trash house.

Eleven oclock at nightThe work of destruction is going on. The whole sky, in the southwest is illuminatedFrom our office we at this moment perceive five distinct firesone apparently in this parish, the others in St. Jamess and at no great distance from us.

MidnightOne fire is raging with unabated fury. We apprehend it to be the whole of the works and buildings on the York estate, in this parish.

Nobody who saw them ever forgot the plantation fires. They would burn and reignite across northwestern Jamaica for the better part of two weeks and rain a curtain of ash down on the trees. Various awestruck witnesses described them as one solid mass of flame, a vast furnace, the skies lighted up in all directions, a chain of signaling lamps that seemed the fruits of a biblical judgment. The whole country, concluded a minister, seemed given up to destruction. More than two hundred blazes were reported in the opening days of the revolt, and in the daytime, they magnified the glare of the tropics and tinted the sun with menace as an organized army of enslaved people held their masters hostage and fought off attacks from the volunteer militia.

The gathering inferno frightened George Lawson to the point that he ordered his post abandoned. I am convinced the contest must be decided in the streets of Montego Bay, he hurriedly wrote the governor before he left for the countryside to link up with another regiment. Professional British soldiers sailed into the harbor three days later and quickly became ensnared in a guerilla war they were ill prepared to fight. Many of them expressed astonishment at the military talent of the enslaved people, who outnumbered whites on the island by ten to one. The rebels built a fortress atop Greenwich Hill and won at least one direct head-to-head confrontation on the battlefield. Indicating an unprecedented level of preparation, some of the dead fighters were found wearing uniforms: blue coats with red sashes.

The entire plantation society of Jamaica came under attack in the largest revolt it had ever faced. One of the richest sugar growers in Jamaica, Richard Barrett, watched the fires with mounting fear from a house in Montego Bay. A fierce defender of slavery, he was the cousin of the poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning and well connected in British society. Barrett scratched out a note to the colonial governor on the fourth night of the insurrection: The militia to a man are zealous and loyal, and no praise can be too high for their courage and conduct. A hint of his panic, however, can be seen in the drops of ink carelessly spilled onto his note.

It is supposed that a hundred plantations and settlements are already in ashes, Barrett wrote. If the rebellion spreads, our force is quite insufficient to put it downall depends on the moral effect of the employment of the Kings troops. Five rebels have been tried by court martial and shot. A woman also condemned was sparedI think she should be hanged.

Those first nights full of fire touched off five weeks of burning, looting, crop destruction, courts-martial, on-the-spot executions, severed heads mounted atop poles, and outright human hunting for sport that shook slaveholding Jamaica to its foundations and sent authorities on a manhunt for the renegade Baptist deacon Samuel Sharpe, who had told his followers the revolt would be a peaceful sit-down strike, only to watch it gyrate out of control and erupt into an inferno. The violence created alarming newspaper headlines across the ocean, forcing Richard Barrett to return to London to answer for the embarrassment in an attempt to save the three-century-old institution of British slavery.

But he could not; the costs were too high. The violence on the Christmas holiday played a central role in convincing the British public that slavery could no longer be countenanced and spurring them to demand change from a dysfunctional Parliament. The effects would also ripple in the United States, where politicians with Southern sympathies had just weathered the revolt of Nat Turner in Virginia and seen how Sharpes rebellion in Jamaica had led directly to British abolition.