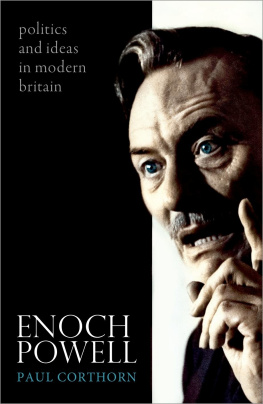

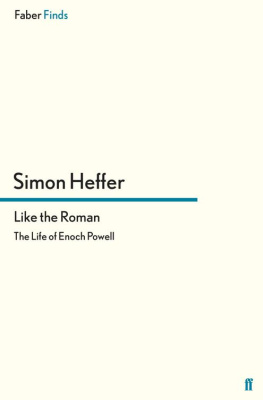

IN THE SHADOW OF ENOCH POWELL

Racism, Resistance and Social Change

FORTHCOMING BOOKS IN THIS SERIES

Race and riots in Thatchers Britain: Simon Peplow

African and Mexican American men and collective violence, 191565: Margarita Aragon

Citizenship and belonging: Ben Gidley

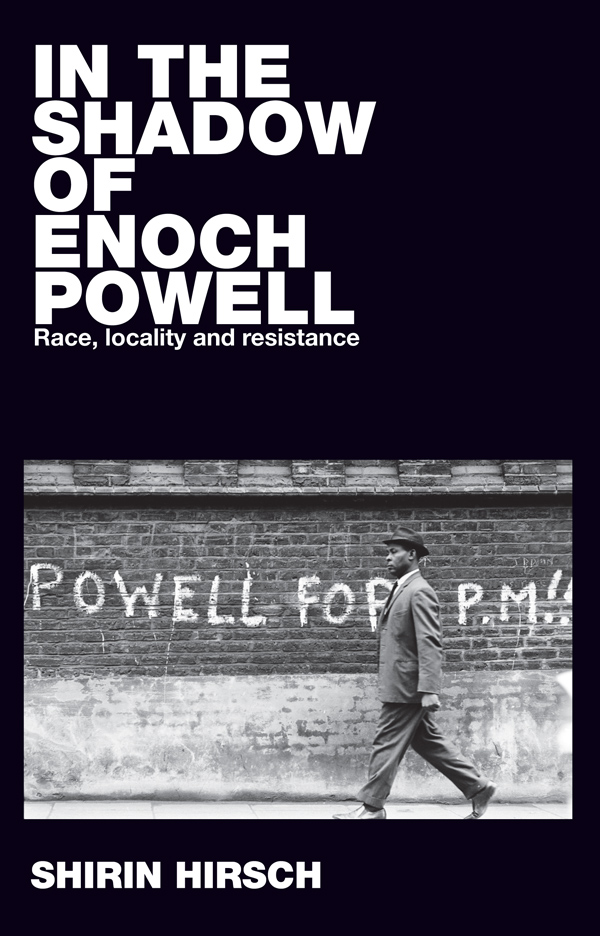

In the shadow of Enoch Powell

Race, locality and resistance

Shirin Hirsch

Manchester University Press

Copyright Shirin Hirsch 2018

The right of Shirin Hirsch to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Published by Manchester University Press

Altrincham Street, Manchester M1 7JA

www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 5261 2739 6 paperback

ISBN 978 1 5261 2737 2 hardback

First published 2018

The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for any external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Typeset by Out of House Publishing

Contents

Patrick Vernon

My parents first arrived to Wolverhampton from Jamaica in the late 1950s. As part of the Windrush Generation they were invited as British subjects to help rebuild the country in the reconstruction and aftermath of the Second World War. It is seventy years on from the arrival of the HMT Empire Windrush, which has come to symbolise not just a generation of Caribbean migrants but also the wider post-war migration from different parts of the former British Empire to the United Kingdom. The book reflects on this history of migration, citizenship and belonging in Wolverhampton and nationally. Shirin Hirsch has been able to research and capture through oral testimony and archive material the environment and mood of the 1950s and 1960s leading up to Powells speech and its impact in Wolverhampton.

Fifty years on, the timing of this book is critical as we reflect on the legacy of Enoch Powells Rivers of Blood speech. Sadly his speech has been used as a barometer for immigration and race relations policy for successive Labour and Conservative governments over the decades as well as inspiring the far right in the UK and across Europe. In his 1968 speech, Powell argued that Britain was mad to take on an extra 50,000 dependants coming to Britain and that there should be stringent limits on black and brown people. Repatriation became Powells political call, and he argued that if this advice was not heeded the country would enter into a racial civil war. Powells prophecy has not come true but his calls to action were certainly brought into mainstream politics. The genealogy of the hostile environment for immigrants can be traced back to Powells words, and has been adapted by Theresa May, first as Home Secretary and now Prime Minister. In this context the Windrush Generation and their children were seen as easy targets by the government for deportation.

In 2018 these government attacks on the Windrush Generation emerged and became a national scandal. It became public knowledge that the Home Office had deported, threatened deportation or prevented the Windrush Generation and their children from re-entering Britain after visits to the Caribbean. They were deemed not British despite the 1948 British Nationality Act. The public reaction, along with the media, campaigners and some politicians, forced the government to U-turn, leading to the resignation of Amber Rudd as Home Secretary. Meanwhile the government policy has led to thousands of victims either losing their jobs, unable to access health care, losing entitlement to pensions and benefits, emotional trauma, suicide and loss of civil liberties where people have been detained and treated as criminals.

There are cases like that of Paulette Wilson from Wolverhampton who came to the UK as a ten-year-old and was on the verge of being deported back to Jamaica in 2018. This attack returned us to Powells narrative, as human beings like Wilson were simply understood as a problem that should never have been allowed to enter the UK. However, the Windrush scandal also highlighted the limits of Powellism in Britain as people have challenged the attacks on Wilson and others, both locally and nationally.

Shirins discussion in this book of Powells reference to education and the use of the expression immigrant children resonates with me, growing up as I did in Wolverhampton during the 1960s and 1970s. I attended Grove Junior School, which Powell attended the opening of in December 1968. He treated my school, plus West Park Primary School, as a political football, treating us as second-class citizens. He articulated a vision in which immigrant children would bring down education standards, especially when we were in large numbers. Apparently we would have a negative impact on white pupils educational prospects. Most of my peers were either born in Wolverhampton or came over as minors from the Caribbean, India or East Africa (ironically there were more Polish and Italian in Wolverhampton but Powell did not see these children as a problem). Despite Powells claims to the contrary, we were British and not immigrants!

The consequence of Powells speech gave the education authority further incentive to treat more of us as educationally sub-normal. A lot of us were bussed around different schools outside Wolverhampton to reduce the number of black pupils and prevent white flight from local primary schools, and finally most of us were not encouraged to develop our educational abilities and thus subsequently went to failing secondary schools prior to the creation of comprehensives and left with no GCSEs. My experience of growing up in Wolverhampton, where the National Front had regular marches, was one of constant fear and the feeling of being under siege in a multicultural neighbourhood. This reminded you every day that being black and British was a struggle for acceptance and belonging.

Luckily some of us were able to fight against the odds and get a decent education and go to university, acquire decent engineering apprenticeships or clerical jobs. But I think Powell has a lot to answer for to the thousands of children of Caribbean and Asian backgrounds whose potential and future careers he blighted.

This book is an important contribution in the history of anti-racist struggle in the Midlands and nationally and it dispels the myth in many local history books of Wolverhampton and the Black Country that we were either invisible or did not fight for our rights. Finally, the book provides the perfect evidence base for the case that Powell does not deserve a blue plaque in his old constituency. There are numerous blue plaques to the great and the good of Wolverhampton but Powell is not one of them. What Wolverhampton now needs are more plaques of people from the Caribbean and Africa, but also the Polish, Italian, Sikh, Hindu and East Asian African communities who have played an important role in the public life of Wolverhampton.

Patrick Vernon is a campaigner and writer and is the founder of the 100 Great Black Britons campaign (www.100greatblackbritons.com/). He is also leading a campaign for a national Windrush day (http://windrushday.org.uk/).

John Solomos, Satnam Virdee, Aaron Winter

The study of race, racism and ethnicity has expanded greatly from the end of the twentieth century onwards. This expansion has coincided with a growing awareness of the continuing role that these issues play in contemporary societies all over the globe.