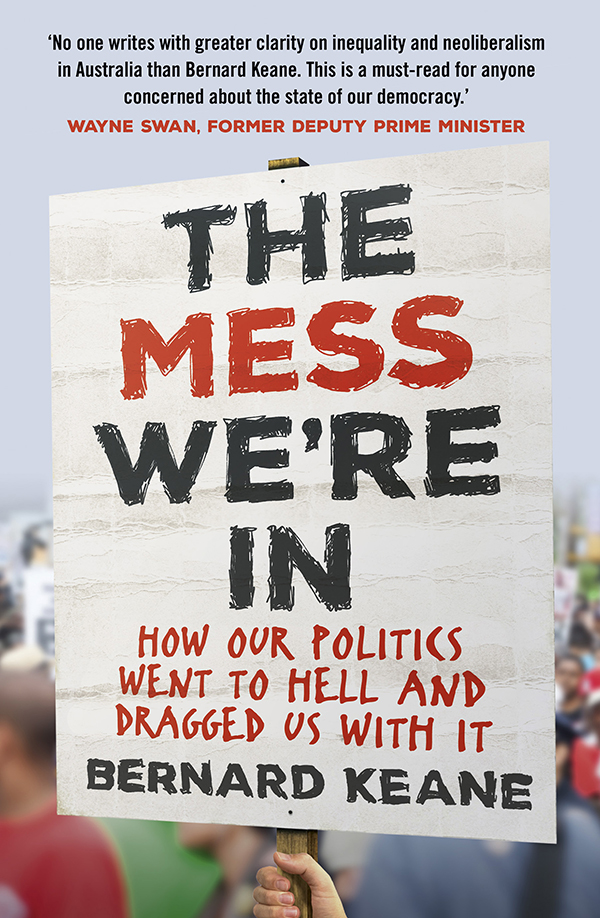

Other books by Bernard Keane

Surveillance

A Short History of Stupid (with Helen Razer)

War on the Internet (ebook)

First published in 2018

Copyright Bernard Keane 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76063 250 2

eISBN 978 1 76063 669 2

Set by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Cover design: Luke Causby/Blue Cork

Cover photographs: Adobe Stock/Luke Causby

For Lincoln

We were not aware that civilisation was a thin and precarious crust erected by the personality and the will of a very few and only maintained by rules and conventions skilfully put across and guilefully preserved.

John Maynard Keynes

CONTENTS

If youre under the age of 70 and live in the Western world, youve never really experienced firsthand what happens when civilisations lose their way. Youre too young to remember the conflagration of World War II. The Great Depression is something you read about in textbooks; the rise of fascism is the subject of black and white documentaries. Thats not to say major events havent occurred in the years since. The Cold War was an epochal conflict that almost saw much of the world incinerated. The social fabric of the United States and European countries seriously frayed in the 1960s. There were recessions every decade from the 1970s on, sending millions into unemployment. But even when things seemed about to go seriously wrong, we managed to stay on course.

Then there was 2016, 2017 and 2018.

Those years didnt see a world war or a depression, of course (well, at least, not by the time of writing). But they gave us a startling sense that things had gotten dangerously out of control, that as a civilisation wed lost our way, that the things we thought we knew were merely convenient illusions. In particular, it made us feel there was something seriously wrong in our societies, that a lot of our fellow citizens were very different people to what wed assumedthey were people who deeply alarmed us.

These years have been terrible for progressives. In Australia, we saw the return of an old disease that many had believed the body politic cured of, with Pauline Hanson elected to the Senate with three (and nearly four) colleagues. Donald Trump became US president, and turned out to be an even more awful leader than expected. The United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union, then voted in an incompetent minority Tory government to implement it. In Europe, far-right parties enjoyed electoral success unseen since the 1930s.

But it wasnt much better for many conservatives. In Australia, the return of Pauline Hanson set alarm bells ringing in the Liberal and National parties. A Coalition government re-embraced protectionism of the kind last seen here in the 1970s, while its incompetence left even supporters speechless. Both Brexit and Trump represented a kind of populism that many on the Right are deeply uncomfortable with. Trump is openly hostile to free trade and blew out the US budget deficit. In the United Kingdom, over 40 per cent of Tory voters backed Remain, especially in wealthy areas in the south-east of England, while Jeremy Corbyn, a figure dismissed as a kind of joking reference to the ideological silliness of the 1970s, suddenly became a credible alternative prime minister. In central and eastern Europe, the monster of anti-Semitism appeared once again.

A new kind of terrorism arose: the elaborately planned mass-casualty events of the early years of the War on Terror gave way to cruder attacks, inspired by Islamic State, that took hundreds of lives in Europe, the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia. Right-wing terrorism grew more common: a fascist murdered a British MP; a neo-Nazi murdered a protester in Charlottesville; Muslims were murdered by white terrorists in London and in Canada. Mass murders by angry males, motivated by misogyny, racism or homophobia became a recurring phenomenon. The United States endured mass shootings, often in schools, with numbing regularity; in 2017, Las Vegas was the site of one of the worst massacres since the wars against native Americans when a single gunman slaughtered 58 people and left hundreds wounded. Meanwhile, mass murder and war crimes occurred regularly in Syria, Yemen and Burma, to the general indifference of Western governments, except to the extent that those conflicts threatened to send new waves of refugees towards them.

Most pervasively, the overall tone of public debate plummeted. Hate speech, misogyny, complete indifference to facts, incoherence and stupidity were now acceptable discourse, on the basis that they were somehow authentic. Even in Australia women, Muslims and LGBTI people were vilified by politicians and commentators.

Whats transpired since 2016 has sometimes felt like a horrible interlude in the slow betterment of society; other times, like a mask has been pulled off to reveal our real diseased face. To determine which one is true, we must investigate what has driven these events in Australia and across the West in the last couple of years, and what underlying causes have interacted to produce the kind of dislocation and political upheaval weve witnessed. Our first step is to sort through the turmoil of 201618 and identify the issues beneath each event: to analyse it, categorise it, work out how it all fits together. Only once weve done that can we begin to examine the causes, and thatll be the task of Parts 2 through 4, where well explore three long-term forces of disruption that have engendered this turmoil. And at the end, Im going to suggest some possible ways to repair the thin and precarious crust of civilisation that Keyneswho has a walk-on role in many of these chapterswarned us needed protecting.

Methodological note

A recurring aspect of my day job as a political writer for Crikey is people approaching me to ask, Why are you so cranky?

I have little to be cranky about. Im a middle-class white male living in a wealthy Western country that even now panders to people like me as a matter of course. My life is free of discrimination, censorship or oppression of any kind. But yes, Im still prone to crankiness, though usually not on behalf of myself.

On whose behalf, then? Why exactly am I so cranky?

Well, I guess, as silly as it sounds, on behalf of facts. If theres one thing that infuriates me, its lies, hypocrisy, inconsistency. Everything summed up by the marvellous word bullshit. If someone lies in public debate, it irrationally enrages me. I cant help it. And Ive ended up in the one profession where Im exposed to little but lies: public debate is riddled with them, like the microbes that swarm over and within our bodies. At least most microbes serve a particular purpose, and may even be of use to the host. Lies, however, only serve the interests of those who utter them. Perhaps lies is the wrong word. What were talking about are not merely lies but deceptions: the half-truth, the twisted or incomplete fact, the wilful misinterpretation, the self-serving inconsistency, pushed with an agenda of misrepresentation.