Did you know...

... that the slave trade brought over

twelve million enslaved Africans across

the Atlantic to the New World?

... that between 1675 and 1700,

officially recognized slaves in the

North American British colonies jumped

from five thousand to twenty-seven thousand?

... that anticolonial and slave uprisings led

to Haitis establishment in the 1790s as

the second independent nation

in the Western Hemisphere?

... nearly two hundred thousand African American

men fought on the side of the Union

during the Civil War?

... the first successful desegregation sit-in

happened in a Chicago restaurant in 1943?

... the U.S. Census declared in 2003 that

the Latino population in America had,

for the first time, surpassed that

of African Americans?

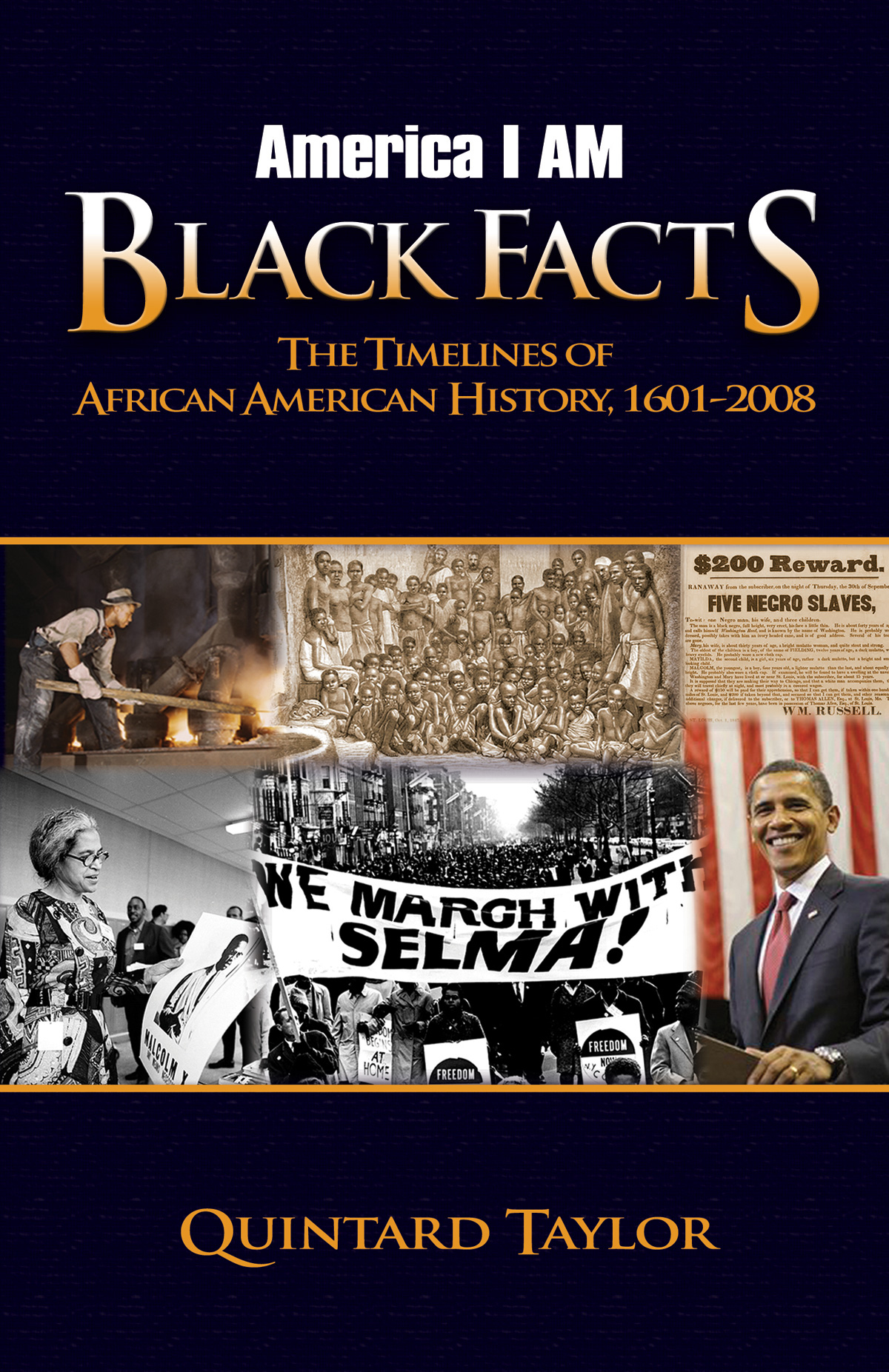

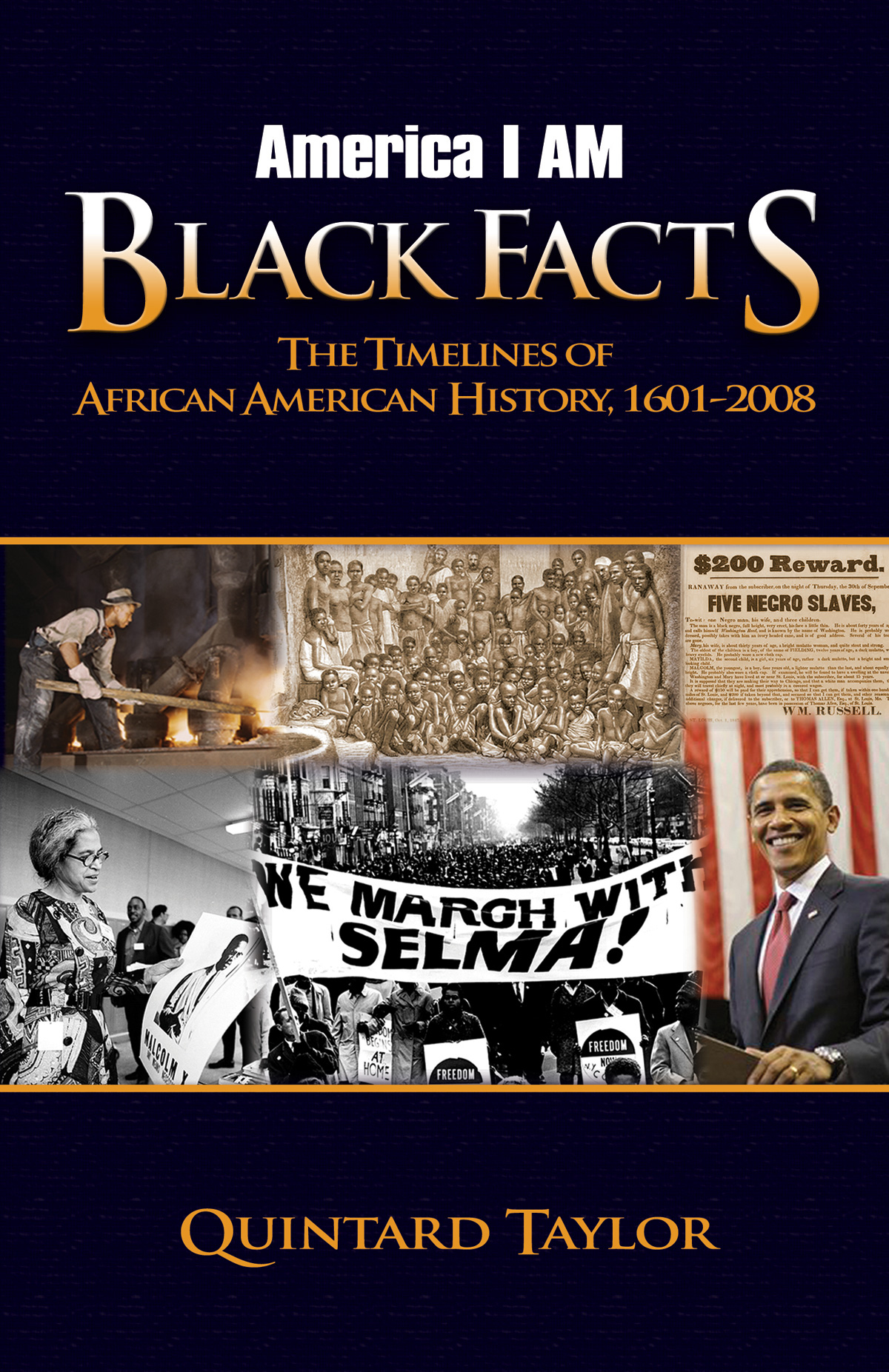

America I AM

BLACK FACTS

Also by Quintard Taylor

AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN CONFRONT THEWEST,

16002000

BUFFALO SOLDIER REGIMENT:

HISTORY OF THE TWENTY-FIFTH

UNITED STATES INFANTRY, 18691926 (WITH JOHN NANKIVELL)

IN SEARCH OF THE RACIAL FRONTIER:

AFRICAN AMERICANS IN THE WEST, 15281990

THE FORGING OF ABLACK COMMUNITY:

SEATTLES CENTRAL DISTRICT,

FROM 1870 THROUGH THE CIVIL RIGHTS ERA

Please visit: Hay House USA: www.hayhouse.com

Hay House Australia: www.hayhouse.com.au

Hay House UK: www.hayhouse.co.uk

Hay House India: www.hayhouse.co.in

Copyright 2009 by Quintard Taylor

Published in the United States by: SmileyBooks, 33 West 19th Street, 4th Floor, New York, NY 10011

Distributed in the United States by: Hay House, Inc.: www.hayhouse.com Published in Australia by: Hay House Australia Pty. Ltd.: www.hayhouse.com.au Published in the UnitedKingdom by: Hay House UK, Ltd.: www.hayhouse.co.uk Published in India by: Hay House Publishers India: www.hayhouse.com

Design: Charles McStravick

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any mechanical, photographic, or electronic process, or in the form of a phonographic recording; nor may it be stored in a retrieval system, transmitted, or otherwise be copied for public or private useother than for fair use as brief quotations embodied in articles and reviewswithout prior written permission of the publisher.

The opinions set forth herein are those of the author, and do not necessarily express the views of the publisher or Hay House, Inc. or any of its affiliates.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Taylor, Quintard.

America I am black facts : the timelines of African American history,

1601-2008 / Quintard Taylor.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-4019-2406-5 (trade pbk.)

1. African Americans--History--Chronology. I. Title.

E185.T288 2009

973.0496073--dc22

200804 6872

Trade paperback ISBN: 978-1-4019-2406-5

eBook ISBN: 978-1-4019-3039-4

TO MY PARENTS,

GRACE AND QUINTARD TAYLOR,

THE FIRST HISTORIANS

I EVER KNEW

CONTENTS

T ime is the great equalizer. No person, race, culture, or nation stands beyond its reach or can alter its inevitable progress. Timelines, the list of events in chronological order, that is, as they happened, allow us to understand the historical past as that equalizer, in its most basic, elemental form, as the evolution of events, episodes, and eras.

For those who study African American history, which has often been subject to blatant and subtle distortion, mischaracterization, and misunderstanding, a timeline can be both corrective and surprisingly informative. It can show what happened, if not why. America I AM Black Facts serves as a starting point for understanding that historical experience. It is, in brief summary, the pivotal moments in the story of the forty million people of African descent in the

United States over the past five centuries. It is also a starting point in the exploration of their relationship with more than one billion black folks around the world. Finally, like the four-year multi-city traveling exhibit, America I AM:The African American Imprint inspired by Tavis Smiley, this volume is a synopsis, a book of facts that chronicles the indelible imprint African Americans have made on the life, history, and culture of the United States and the world.

The six timelines presented as separate chapters in this volume provide a perspective that often does not appear in narrative or analytic histories of black America. The year 1892 provides a cogent example. The academic historian usually focuses on 1892 as the year when a record number of people, 161 African Americans and 69 whites, were lynched in the United States. Yet the timeline shows that in the same year, Sissieretta Jones became the first African American to perform at Carnegie Hall, and the National Medical Association was formed in Atlanta. Eighteen hundred ninety-two was also the year that three companies of the Twenty-fifth Infantry, the famous Buffalo Soldiers, were sent by President Benjamin Harrison into northern Idaho to reestablish order following an outbreak of violence by striking white miners and the year that the first intercollegiate football game between black American colleges took place in Charlotte, North Carolina, between Biddle University (now Johnson C. Smith University) and Livingston College. Biddle won the contest, 40, on a snow-covered field in Charlotte on December 27. Thus to African Americans living at that time, the seminal event of the year depended upon a host of factors, including ones gender, class status, education, political persuasion, and state or regional home. In other words, the timelines allow us the opportunity to see the world not from our contemporary vantage point looking backward at what we now assume was most important, but more accurately as it might have appeared to those at the time.

Of course for millions of black folks in 1892, the daily struggle to survive overshadowed any and all of these events. Complicating matters further, communication systems in 1892 may have left thousands more unaware of most of these developments. Nonetheless, each event in its own way mattered. Their consequences may or may not have escaped contemporaries, but certainly those consequences would impact the generations that followed.

The communication revolution of the twentieth century quickly ended that isolation even as it presented new challenges to African America. The seven-decade-long great migration of African Americans from the South to the North, or more accurately from the rural South to the urban North, West, and South, ushered in a new period of spatial concentration that facilitated various types of communication. Beginning with the 1920s and 1930s, African Americans created what historians have described as self-conscious black publics. These new publics emerged as more and more African Americans had access to vital information about themselves as well as the United States, Africa, and the rest of the world. Thus they became more willing to openly challenge general media images of themselves, their history, and their culture and to craft counternarratives that reflected their own sense of identity and peoplehood. Coupled with rising levels of education and prosperity, which both caused and were a consequence of civil rights struggles, as well as technological innovations, including mass-circulation newspapers, radio, television, and, most recently, the Internet, more and more African Americans began to shape the collective culture and history of black America and the world beyond. The dramatic increase in the number of twentieth-century entries in chapter 5 reflects this change.

Next page