Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

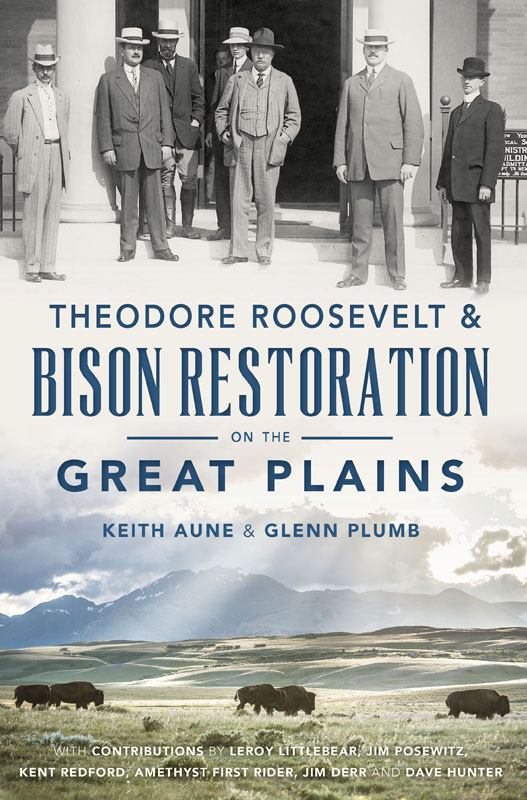

Copyright 2019 by Keith Aune and Glenn Plumb

All rights reserved

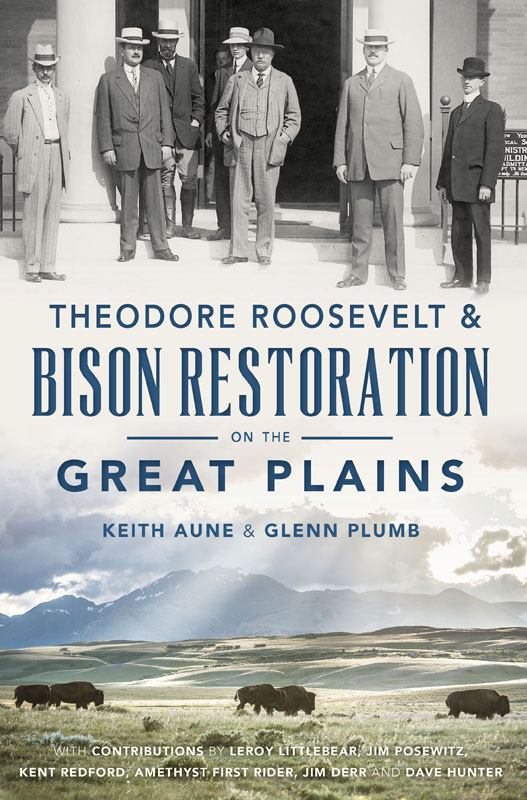

Cover images: Front, the Blackfeet Reservation with Glacier National Park in the background.

Courtesy of Tony Bynum. Back, bison at Grand Teton National Park. Courtesy of Jeff Burrell.

First published 2019

e-book edition 2019

ISBN 978.1.43966.684.5

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018960985

print edition ISBN 9781467135696

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the authors or The History Press. The authors and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

This book explores several important histories, not necessarily in chronological order, that otherwise risk being perceived as independent narratives. The reader is offered the opportunity to appreciate these multiple histories as they unfolded, sometimes pollinating the greater narrative and sometimes withering on the vine. Upon this reflection, there is an opportunity to look forward over the horizon, touching on great tragedy and potential redemption. The book is organized to convey these histories through thematic sections, including the disappearance of bison, their arrival back into the scene (recovery), the awakening of a conservation movement and the convergence of this history with modern times. Throughout, we intersperse short interludes about legacy bison and people who have helped shape these histories up through contemporary times.

The disappearance of bison from the land has been told and retold many times before. Herein, we reframe the story by highlighting human dimensions of the events, along with the real-time struggle to survive the catastrophe. The arrival of bison back to the land emphasizes the champions who brought bison back from the brink. In this section, we focus on Theodore Roosevelt and others who arrived onto the scene and launched the great story of American wildlife conservation, with bison at center stage. The great American awakening to the preservation of bison is a key part of the rise of an entire national conservation ethic that, at first, was not welcomed but eventually became accepted by a nation in transformation. In this section, we profile the development of new groups and organizations dedicated to conservation of wildlife and wild places, a new idea presented to the world. We especially highlight the American Bison Society, wholly dedicated to the business of saving this wild and iconic species. The eventual convergence of these conservation ideals into restoration activities and civic action by individuals and organizations was not predictable or anticipated by the people involved. They might have remained disparate endeavors but for the efforts of Roosevelt and other conservation champions who connected them into a cohesive movement at a specific time in history. This convergence of people, places and ideas served to prevent the extinction of species and protect critical wildlands, even to the extent that the names bison and buffalo are now wholly synonymous. This convergence of bison, the buffalo people, visionary individuals, non-governmental organizations and governance has led us toward a future fraught with both peril and promise.

WHATS IN A NAME?

Why is there an extensive interchange in the scientific and vernacular use of the names bison and buffalo? It may be that this interchange contributes to confusion about efforts to conserve the animal, as it wouldnt be unreasonable for a person to wonder why we should agree on complex conservation efforts when we cannot even agree on the animals proper name! When Linnaeus first classified the bison in 1758 for his tenth edition of Systema Naturae, he assigned the animal to the genus Bos, which includes domestic cattle. During the nineteenth century, taxonomists determined that there was adequate anatomical distinctiveness to warrant assigning the animal to its own genus, Bison, as compared to the true African cape buffalo (Syncerus caffer) or Asian water buffalo (Bubalus spp.). Indeed, the interchange between the words bison and buffalo freely occurs in documents written by federal, state and local government; tribes; and private for-profit and nonprofit sectors (e.g., United States Department of Interior Bison Conservation Initiative, Inter-Tribal Buffalo Council, National Bison Association and Buffalo Field Campaign), as well as even between and within science publications.

Historically, the animal we now recognize as the American bison was referred to by Euro-derivatives, such as bisonte, buffes, buffalo and buffles. Tribal names also varied considerably, with the Sioux tatanka and Blackfoot iinnii having received widespread reference and usage. Notwithstanding any scientific taxonomic designation, the common name is now interchanged freely between buffalo and bison without apparent or important conflict in meaning or understanding toward effective stewardship. Indeed, there seems little widespread interest or need to force adoption of either as a single common name, and as such, it appears that the continuing synonymous interchange from the nineteenth century to present has now become the entrenched preference that integrates prevailing societal agility with a cultural penchant for nostalgia, as Plumb, White and Aune noted in their 2014 comprehensive scientific review of the American Bison (Bison bison).

HOPE FROM BISON AND HUMAN HISTORIES

By Kent Redford

Bison are, and always have been, complicated animals, despite having limited behaviors and leading the fairly straightforward life of a large herbivore. Rather, the complications come from bisons long history with humans, a path traveled together that has left both parties with intertwined hybrid histories.

Originating in Europe or Asia, the ancestors of North American bison were of great importance to early humans and were featured prominently in cave art such as at the Chauvet Cave in France. Wisent, or European bison, were themselves hybrids between the steppe bison and the auroch, or European ox, the progenitor of European domesticated cattle. Reduced to even fewer numbers than American bison, wisent survived only in zoos, where some were crossbred with American bison, with these hybrid animals bringing the distant lineage back to its place of origin.

North American bison came to this continent across the Bering Strait and survived through climate change and the extinction of other, larger, species of bison. They became vital parts of the lives and economies of numerous Native American groups, a reliance that only increased when horses were (re) introduced to North America. Mounted bison hunting rapidly became such a key part of the culture of Great Plains tribes that many European American observers assumed it had always been so. The ensuing bison culture was a hybrid one of European domesticated animals, Native American lifeways and bison cultural knowledge.

The relentless westward spread of Euro-Americans brought with it decimation of the bison herds, first through the robe trade and then, in the most ignominious of fashions, through the trade in bison bones. All that was left of the tens of millions of bison that once flourished in North America was converted into pigment and fertilizer and even used to whiten sugar. The destruction of the Great Plains grasslands for agriculture was aided by the bones of the very animals that once defined it, a hybrid mixture of prairie past and prairie future.

Next page