Published in 2020 by New York Times Educational Publishing in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. 29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Contains material from The New York Times and is reprinted by permission. Copyright 2020 The New York Times. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2020 The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved. Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

First Edition

The New York Times

Alex Ward: Editorial Director, Book Development

Phyllis Collazo: Photo Rights/Permissions Editor

Heidi Giovine: Administrative Manager

Rosen Publishing

Megan Kellerman: Managing Editor

Michael Hessel-Mial: Editor

Greg Tucker: Creative Director

Brian Garvey: Art Director

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: New York Times Company.

Title: Populism / edited by the New York Times editorial staff.

Description: New York : New York Times Educational Publishing, 2020. | Series: Changing perspectives | Includes glossary and index.

Identifiers: ISBN 9781642822335 (library bound) | ISBN 9781642822328 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781642822342 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: PopulismJuvenile literature.

Classification: LCC JC423.P678 2020 | DDC 320.5662dc23

Manufactured in the United States of America

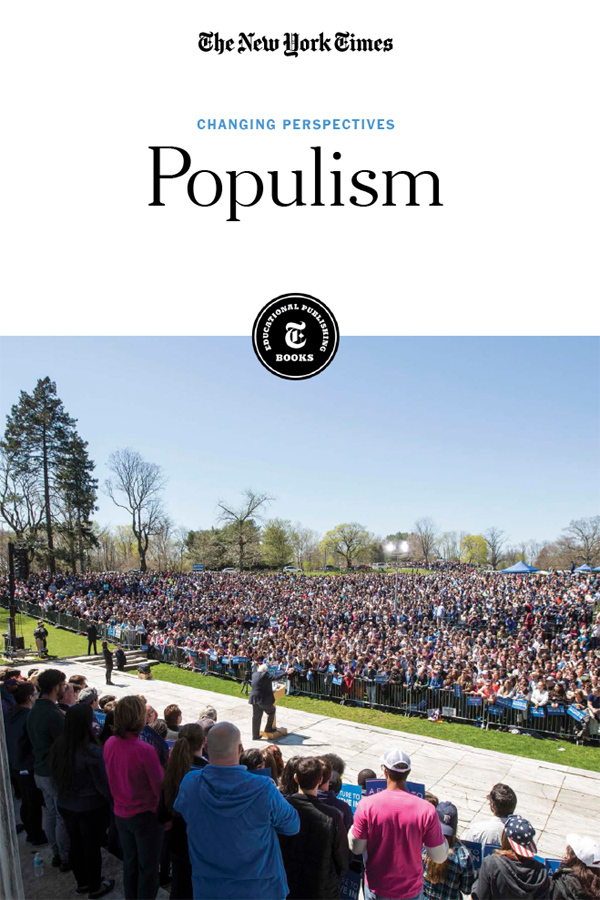

On the cover: U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders speaks during a rally in Providence, R.I., April 24, 2016; Scott Eisen/Stringer/Getty Images.

Introduction

THE WORKER, THE FARMER, the commonweal, the silent majority, the ninety-nine percent: the people. The idle holders of idle capital, the railroads, the banks, the pointy-headed intellectuals, the one percent: the elites.

These names come from one of the most significant political styles of modern democracy: populism. Unlike other isms, populism is not a particular platform but is instead a pattern political movements follow. Populist appeals have appeared all around the world from a range of positions, pitting the people against the elites however vaguely defined. Today, we encounter populism yet again, directly challenging established political processes.

The populist movement began in the United States after the Civil War, a period of rapid industrialization and social change. The Farmers Alliance and unionized laborers organized against social inequality and the concentration of economic power in railroads, banks and corporations. This movement made aggressive and plainspoken appeals for policies that would attend to the needs of the people. These included antitrust and worker protection laws, inflationary monetary policies and other goals later taken up by the progressive movement. Populism soon reached the major political parties but was often divided over race, immigration and religious difference. These challenges raised the core problem of populism: does the people truly mean everyone?

After World War I, the competing ideologies of communism and fascism appeared, channeling populism into political power. Communism called for workers to overthrow the capitalist system, while fascism called for militant authoritarian nationalism. When the Great Depression struck, many believed that one of these two alternative political systems would replace traditional democracy. In the United States, populists flirted with both of these ideologies. Some, like Huey Long and Earl Browder, advocated for socialist policies; others, like radio priest Charles Coughlin, began to veer toward a fascist model. The United States sided against fascism during World War II, and populisms reputation became associated with totalitarian ideology.

After the war, American public intellectuals examined populism with a critical eye, and it became common to muse on populisms history and causes. These writings were occasioned by independent politicians like George Wallace and Ross Perot, whose populist styles made headlines despite their electoral failures. At the same time, two very different populist movements appeared in the world: anti-immigration politics in Europe and political Islam in the Middle East.

At the turn of the 21st century, the economy was globalized by new technologies. This process echoed the 19th century in its enormous growth and increased income inequality. In response, populism again took center stage. A revived left-wing populism included protests against the World Trade Organization and a pink tide of Latin American populists like Hugo Chvez and Evo Morales. These movements culminated in the Occupy Movement, which popularized the concept of the wealth gap between the ninety-nine percent and the one percent. At the same time, the Tea Party movement gave a populist basis to Republican criticisms of Barack Obama and government spending. In parallel, European populists criticized the European Unions enforced austerity policies, which cut social services.

By the end of Obamas presidency, populist movements had shifted rightward and begun winning elections around the world. In Europe, smaller parties gained influence by appealing to voters fears of refugees from Syria and the greater Middle East. In the United States, the 2016 presidential election was a dramatic play of conflicting populist visions. Bernie Sanders, a self-avowed socialist, based a popular but ultimately unsuccessful primary campaign on criticizing the billionaire class. Donald Trump surprised the world by winning the presidency with a populist attack on immigration and on establishment rival Hillary Clinton. As a result of these elections, populism became a dominant force in global politics.

Bernie Sanders supporters at a presidential campaign rally in 2016. Sanders, like Donald Trump and other recent populist politicians, drew large crowds to hear his speeches.

As the world is shaped by the visions of these many incarnations of populism, there is simultaneously a danger and an opportunity. At the heart of it, populism represents an enormous burst of energy into the democratic process. The results of that often unfocused energy lie not just in the people but in whoever channels that energy for political power. For those seeking to use that energy for their own ends, the result is often paranoia and misdirection, where legitimate grievances are channeled into fears, leveraged for the pursuit of power. For those seeking to share that power with the people they represent, the result is a renewal of democracy itself.

CHAPTER 1

Farmers and Laborers Build a Movement

The populist movement was based on agricultural and industrial labor movements alongside other spontaneous demonstrations that appeared after the Civil War. These movements were critical of railroad monopolies, trade tariffs and the gold standard, all of which were seen as favoring the wealthy over the poor. The populist movement found initial success in the Democratic Party but lost momentum due to internal divisions on race and foreign policy. Eventually, the Republican Party would win elections on a platform first proposed by the populist movement.

The National Grange: Declaration of Its Objects and Purposes.

BY THE NEW YORK TIMES | FEB. 12, 1874

ST. LOUIS, FEB. 11.