Professor Ian Lowe AO is emeritus professor of science, technology and society at Griffith University in Brisbane, as well as being an adjunct professor at Sunshine Coast University and Flinders University. His previous books include A Big Fix , Living in the Hothouse , A Voice of Reason: Reflections on Australia and Bigger or Better? Australias Population Debate . Professor Lowe has been a referee for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme and the Millennium Assessment. He attended the Geneva, Kyoto and Copenhagen conferences of the parties to the Framework Convention on Climate Change. He was a member of the Australian delegation to the 1999 UNESCO World Conference on Science and has served on many advisory bodies to all levels of government. He was president of the Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF) from 2004 to 2014, and in 2009 the International Academy of Sciences, Health and Ecology awarded him the Konrad Lorenz Gold Medal. He is a fellow of the Australian Academy of Technology and Engineering.

Professor Ian Lowe AO is emeritus professor of science, technology and society at Griffith University in Brisbane, as well as being an adjunct professor at Sunshine Coast University and Flinders University. His previous books include A Big Fix , Living in the Hothouse , A Voice of Reason: Reflections on Australia and Bigger or Better? Australias Population Debate . Professor Lowe has been a referee for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme and the Millennium Assessment. He attended the Geneva, Kyoto and Copenhagen conferences of the parties to the Framework Convention on Climate Change. He was a member of the Australian delegation to the 1999 UNESCO World Conference on Science and has served on many advisory bodies to all levels of government. He was president of the Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF) from 2004 to 2014, and in 2009 the International Academy of Sciences, Health and Ecology awarded him the Konrad Lorenz Gold Medal. He is a fellow of the Australian Academy of Technology and Engineering.

For Maven Cordelia and all of her generation

CONTENTS

Introduction

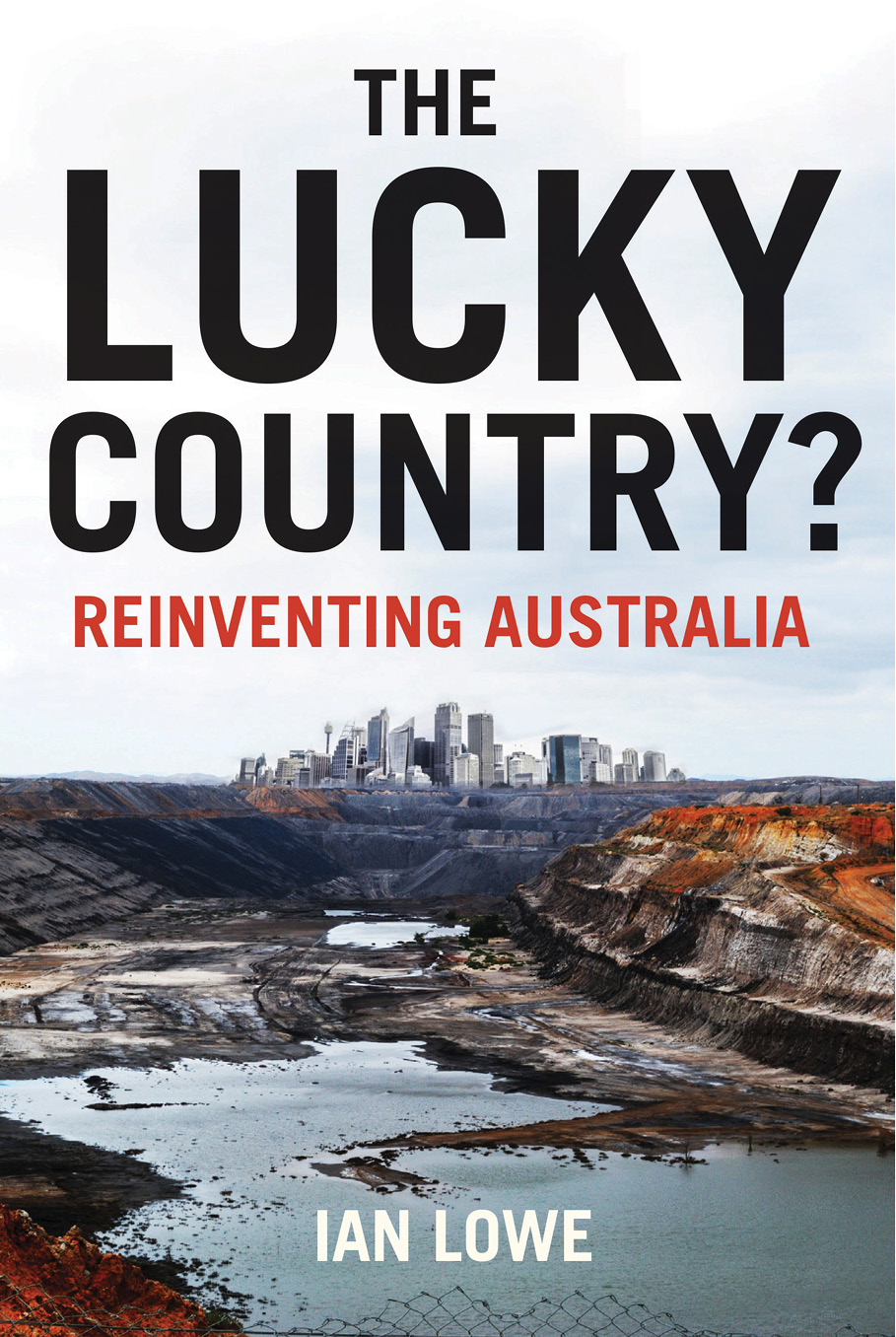

In his iconic 1964 book, Donald Horne described Australia as a lucky country run mainly by second-rate people who share its luck. He went on to say that we live on other peoples ideas and that most of our leaders (in all fields) so lack curiosity about the events that surround them that they are often taken by surprise. His book caused a sensation at the time and became a runaway bestseller. The striking cover, an Albert Tucker painting of a sun-bronzed Aussie, appealed to the traditional Australian image of a country defined by its rural lands and their produce. The phrase the lucky country quickly became part of the language, though its message was often misrepresented by people who had not even read the book, or had skimmed quickly through it and missed the irony of the title.

Donald Horne was a remarkable Australian. He grew up in a country town, but he moved with his parents to Sydney while he was at school. He began to study at the University of Sydney with the intention of becoming a teacher, but his formal education was interrupted when he was conscripted into the army during World War II. After the war he drifted through a brief dalliance with the diplomatic service into a career as a journalist, rising through the ranks to edit magazines. When it was rumoured that he was about to be sacked from the editorship of The Bulletin , then a popular publication, the University of New South Wales offered him a post in its Faculty of Arts. He became a prominent academic in the politics department, achieving the distinction of being promoted to professor without even having a bachelors degree! A few months before he died in 2005, the University of Sydney finally conferred an honorary Doctor of Letters on the man who was probably their most famous drop-out. Glyn Davis, now vice-chancellor of Melbourne University, who as an honours student was supervised by Horne, described him as a familiar public intellectual in Australia, a man who helped the nation understand itself. Davis observed that The Lucky Country was both description and program calling for government to encourage the innovation missing from public and business life. It resonated with the community because it was such a perceptive analysis of what is good about Australia, as well as what we could do better. Davis attributed the breadth of Hornes understanding of Australia to the many roles he had filled: student, soldier, diplomatic cadet, young journalist, editor, advertising executive, academic. He was truly a unique individual.

Reflecting on the books reception 35 years after it was first published, Horne wrote about the way his argument had been misunderstood or deliberately misrepresented. He said, misuse of the phrase the lucky country, as if it were praise for Australia rather than a warning, has been a tribute to the empty-mindedness of a mob of assorted public wafflers. When the book first came out, people had no doubt the phrase was ironic. Twisting it around to mean the opposite of what was intended has silenced the three loud warnings in the book about the future of Australia. The first of these three loud warnings was that it is essential to accept the challenges of where Australia sits on the map. These challenges include how we develop relationships with our Asian neighbours, with whom we have tended to engage on purely economic terms; how we reconcile our colonial history of dispossessing Australias original inhabitants; and how we develop our foreign policy and defence strategies in the complex world of the AsiaPacific, recognising the competing interests of the two great powers, China and the USA, as well as a significant group of middleweights like ourselves. Hornes second warning was the need for a bold redefinition of what the whole place adds up to now, which requires us to recognise that Australia has changed fundamentally in recent decades and have a serious public discussion about societal values, population growth and what kind of country wed like to become. Obviously that process would be facilitated if we were to elect visionary leaders who were willing and able to guide, or at least participate in, the public discussion. His third warning saw a need for a revolution in economic priorities, especially by investing in education and science, which have been sacrificed in this country to privilege markets and the pursuit of endless growth, while we further tether ourselves to a globalised economy that puts our well-being in the hands of forces we cant control.

Writing in 1998, Horne observed that these same three warnings should be repeated, with the amplifying knob turned up. If he were alive today, he would certainly think that the three warnings are still valid, more than 50 years after he originally issued them. In this book, I revisit these warnings to show you why they are still relevant today; if anything, they are more urgent because they have been neglected for 50 years by politicians content to drift with the random tides of international affairs. I am also compelled to add a warning of my own: the environmental challenges we face simply can no longer be ignored. Hornes three warnings on geography, society and the economy must all be filtered through the lens of our precarious environmental situation. The devastatingly extreme weather patterns that come with climate change, the loss of biodiversity, the breakdown of the Earths ecosystems and our unsustainable use of finite resources all affect our future prospects.

In 2015, the need for change was signalled by a UN report on progress toward sustainability. It showed that Australia ranks 18th out of the 34 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries: below the UK, New Zealand and well below Canada. The rating was based on 34 indicators covering economic, social and environmental progress. Australia ranked among the worst of all the affluent countries on such indicators as our level of resource use, the municipal waste we generate, the greenhouse gases we use for each unit of economic output and our obesity rate. We were also well below the average on social indicators such as the level of education we reach, the gender pay difference and percentage of women in parliament, economic indicators such as the poverty rate and the degree of inequality, as well as environmental indicators such as how much land we protect and our share of renewable energy. Perhaps most worrying, we are also well below average in our capacity to monitor progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals. As the old adage goes, you cant manage what you dont measure.

Professor Ian Lowe AO is emeritus professor of science, technology and society at Griffith University in Brisbane, as well as being an adjunct professor at Sunshine Coast University and Flinders University. His previous books include A Big Fix , Living in the Hothouse , A Voice of Reason: Reflections on Australia and Bigger or Better? Australias Population Debate . Professor Lowe has been a referee for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme and the Millennium Assessment. He attended the Geneva, Kyoto and Copenhagen conferences of the parties to the Framework Convention on Climate Change. He was a member of the Australian delegation to the 1999 UNESCO World Conference on Science and has served on many advisory bodies to all levels of government. He was president of the Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF) from 2004 to 2014, and in 2009 the International Academy of Sciences, Health and Ecology awarded him the Konrad Lorenz Gold Medal. He is a fellow of the Australian Academy of Technology and Engineering.

Professor Ian Lowe AO is emeritus professor of science, technology and society at Griffith University in Brisbane, as well as being an adjunct professor at Sunshine Coast University and Flinders University. His previous books include A Big Fix , Living in the Hothouse , A Voice of Reason: Reflections on Australia and Bigger or Better? Australias Population Debate . Professor Lowe has been a referee for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the International Geosphere-Biosphere Programme and the Millennium Assessment. He attended the Geneva, Kyoto and Copenhagen conferences of the parties to the Framework Convention on Climate Change. He was a member of the Australian delegation to the 1999 UNESCO World Conference on Science and has served on many advisory bodies to all levels of government. He was president of the Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF) from 2004 to 2014, and in 2009 the International Academy of Sciences, Health and Ecology awarded him the Konrad Lorenz Gold Medal. He is a fellow of the Australian Academy of Technology and Engineering.