ABRAHAM H. MASLOW

DEBORAH C. STEPHENS and GARY HEIL

This book is dedicated to my daughters, Ann and Ellen.

Contents

xix

xxi

... 257

Foreword to the New Edition

37 YEARS LATER

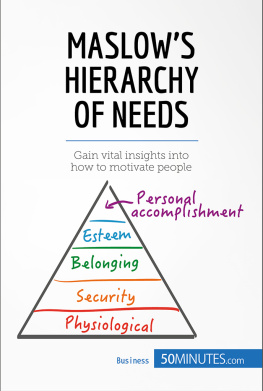

It's amazing, isn't it, that a book out-of-print for almost 37 years, a book that just barely sold its first printing and then virtually vanished from view-into oblivion really, without even a whimper-has suddenly burst upon the scene, piquing just about everybody's interest. Intriguing thousands of Maslow fans and thousands of others who mistily remember his name from their undergraduate classes or when phrases like self-actualization or peak experiences or hierarchy of needs come to mind or scroll across their computer screens.

Why the book disappeared still bedevils me. Maybe it was the title. I had implored Abe to use a more reader-friendly title but who was I to challenge the maze of phrases and seductive writing. The original publishers, though, went ballistic but Abe stubbornly held out for, yes, Eupsychian Management.

But more likely, it was the times. A rather complacent industrial America, famously supreme since World War II, was not particularly interested in business books, especially by a psychologist who had no business experience to speak of. In addition to that daunting title, Abe writes in a discursive manner-thought pieces, nuggets thrown about, rough drafts, like artists' sketches or finger exercises for the violin.

The entries in this book were transcribed word-for-word from his journals. When Abe first showed his journals to me, I said very forcefully, "you must publish them." He resisted for months, said they were just "works in progress," only drafts, "not academic," "I'm new to this field," and so on. One excuse after another. Finally, reason prevailed. I talked him into publishing his journals and then found a publisher whose editor, I'm sure, didn't truly appreciate the book's meaning, asking me in confidence if English was Abe's second language.

There are sections of the book that are hilariously innocent and other parts which are terrifyingly prescient and penetrating. But there are no neat little formulaic paradigms-if you can bear reading that word one more time. Nor are there 19 Rules for Effective Anything. What you will experience throughout this marvelous book is a genius-at-play with all of his elegant ruminations, a thoughtful writer who throughout his life cultivated a beginner's mind. As he says in the Preface, "A novice can often see things that the expert overlooks."

He takes on and challenges the major management figures of the 1960s who were then writing about the industrial workplace, notably Drucker, McGregor, Rogers, and Likert. Always in a friendly, nonadversarial way, but in a way that you know must have turned those iconic heads. Drucker claims that Abe wrote this book to bring him and McGregor down to earth. I doubt that that was the primary motive, but Abe certainly does question the assumptions of those giants. But as you continue reading, I hope you'll notice some other things as well, many of which I either missed or didn't fully understand 35 years ago.

For example, Abe was one of the earliest figures to realize that, "the industrial situation may serve as the new laboratory for the study of the psycho-dynamics, of high human development, of the ideal ecology for the human being." His prescience was also quite extraordinary. In the last chapter, to take only one example, he foresees, with terrifying accuracy the eventual downfall of the Soviet Union and America's future success because "of the growth-fostering tendencies in industry ... If the Americans can turn out a better type of human being than the Russians [remember, dear reader, he wrote this at the peak of the Cold War] then this will ultimately do the trick. Americans will simply be more loved, more respected, more trusted, etc., etc."

There are two other things about this book I'd like to mention. One is how politically incorrect he sounds today and how downright courageous Abe has always been. Read his chapter on the Aggridants, where he discusses the dilemma of democracy: what do we do with superior individuals? What do we do with extreme disparities in talent? He tackles issues that everybody ducked in the 1960s and are still ducking today. Abe has always asked the BIG questions. This book tries to deal with two major questions or moral edicts throughout but are worth repeating over and over again: "How good a society does human nature permit?" "How good a human nature does society permit?"

Maybe that helps to explain my opening questions: Why has the promise of republication generated such perfervid interest and why did the book so unceremoniously migrate over to the remaindered shelf so soon after publication? The first question is a little easier to answer. The problems organizations face today are far more vexing than the problems they had to address in the 1960s: globalization, intense competitiveness, galloping technology, change/change/change. As to the second question, now that I reread the book, it's very clear. The book raises tremendously threatening questions and Abe always thought that the primary goal of science was "to shove truth down the reluctant throat." Maybe our throats or even our minds are now ready for Maslow's profound medicine.

Abe Maslow requires no explanation or interpretation. He is an open book, knowledgeable by his words and his treasured person. The first sentence in one of Abe's most important books, Toward a Psychology of Being, published in 1962:

There is now emerging over the horizon, a new conception of human sickness and of human health, a psychology that I find so thrilling and full of wonderful possibilities that I yield to the temptation to present it publicly even before it is checked or confirmed, and before it can be called reliable scientific knowledge.

It is all there in that one sentence-a sentence that has sentenced psychology to a new life; that has turned it inside out or more precisely outside in: to gain truth through personal experience, be a "courageous knower."

Science to Abe was a way of life and love-his poetry and debureaucratizing it (or as he would prefer-resacralizing it) was his goal. Abe was a conquistador-a lone one for many years-always advancing with courage and charm like the most seductive crusader.

He wrote in his last book, The Psychology of Science:

The assault troops of science are certainly more necessary to science than its military police. This is so even though they are apt to get much dirtier and to suffer higher casualties, but somebody has to be the first one through the mine fields.

Science was his poetry, his religion, his wonder. He wrote, also in his Psychology of Science:

Science can be the religion of the nonreligious, the poetry of the nonpoet, the art of the man who cannot paint, the humor of the serious man, and the love making of the inhibited and shy man. Not only does science begin in wonder, it also ends in wonder.

I quote lavishly from Abe's own work, because his work was his life, and to know one is to greet the other. I first got to know Abeor encounter him (like many of us) through one of his books. It was my senior year at Antioch College, and while taking a tutorial with the then president, Douglas McGregor, he recommended a book on abnormal psychology written by Maslow and Mittelmann.

It was a breath of fresh air. It was a book that really drew me into psychology as a calling. I'll never forget in this book, in the frontispiece, there were two panel pictures: one that showed a group of happy-looking gurgling babies in the maternity room of a children's hospital-newborn babies-and just beneath that was another panel showing a group of people-haggard, drawn, and sallow-crowded into the New York subway hanging on, with the most baleful looks, to the straps above their heads, and through the windows you could see these sallow faces. And the caption beneath these two panels was, "What happened?" And that's the question that Abe spent most of his life trying to answer.