ALSO BY IAN KERSHAW

Hitler, 18891936: Hubris

Hitler, 19361945: Nemesis

Fateful Choices: Ten Decisions that Changed the World, 19401941

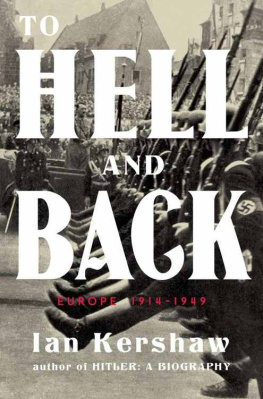

To Hell and Back: Europe 19141949

The Global Age: Europe 19502017

PENGUIN PRESS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright 2022 by Ian Kershaw

Penguin Random House supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for every reader.

First published in Great Britain by Allen Lane, an imprint of Penguin Random House UK, 2022.

Illustration credits appear on .

library of congress cataloging-in-publication data

Names: Kershaw, Ian, author.

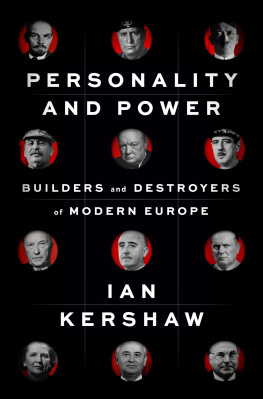

Title: Personality and power: builders and destroyers of modern Europe / Ian Kershaw.

Description: New York: Penguin Press, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022038162 (print) | LCCN 2022038163 (ebook) | ISBN 9781594203459 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780593492567 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Heads of stateEuropeHistory20th centuryCase studies. | EuropePolitics and government20th centuryCase studies. | Political leadershipEuropeHistory20th centuryCase studies.

Classification: LCC D412.7 .K47 2022 (print) | LCC D412.7 (ebook) | DDC 940.53/1dc23/eng/20220816

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022038162

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022038163

Cover design: Christopher Brian King

Cover photographs: (Top to bottom, left to right) Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, David Cole / Alamy Stock Photo; Benito Mussolini, Alamy Stock Photo; Adolf Hitler, Alamy Stock Photo; Joseph Stalin, Courtesy of the Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-32833; Winston Churchill, Yusuf Karsh / Alamy Stock Photo; Charles de Gaulle, Alamy Stock Photo; Konrad Adenauer, Alamy Stock Photo; Francisco Franco, Alamy Stock Photo; Josip Broz Tito, Alamy Stock Photo; Margaret Thatcher, David Cole / Alamy Stock Photo; Mikhail Gorbachev, Ronald Reagan Presidential Library & Museum / Courtesy National Archives; Helmut Kohl, Alamy Stock Photo

Adapted for ebook by Cora Wigen

pid_prh_6.0_141716077_c0_r0

In Memory of Stephen

Contents

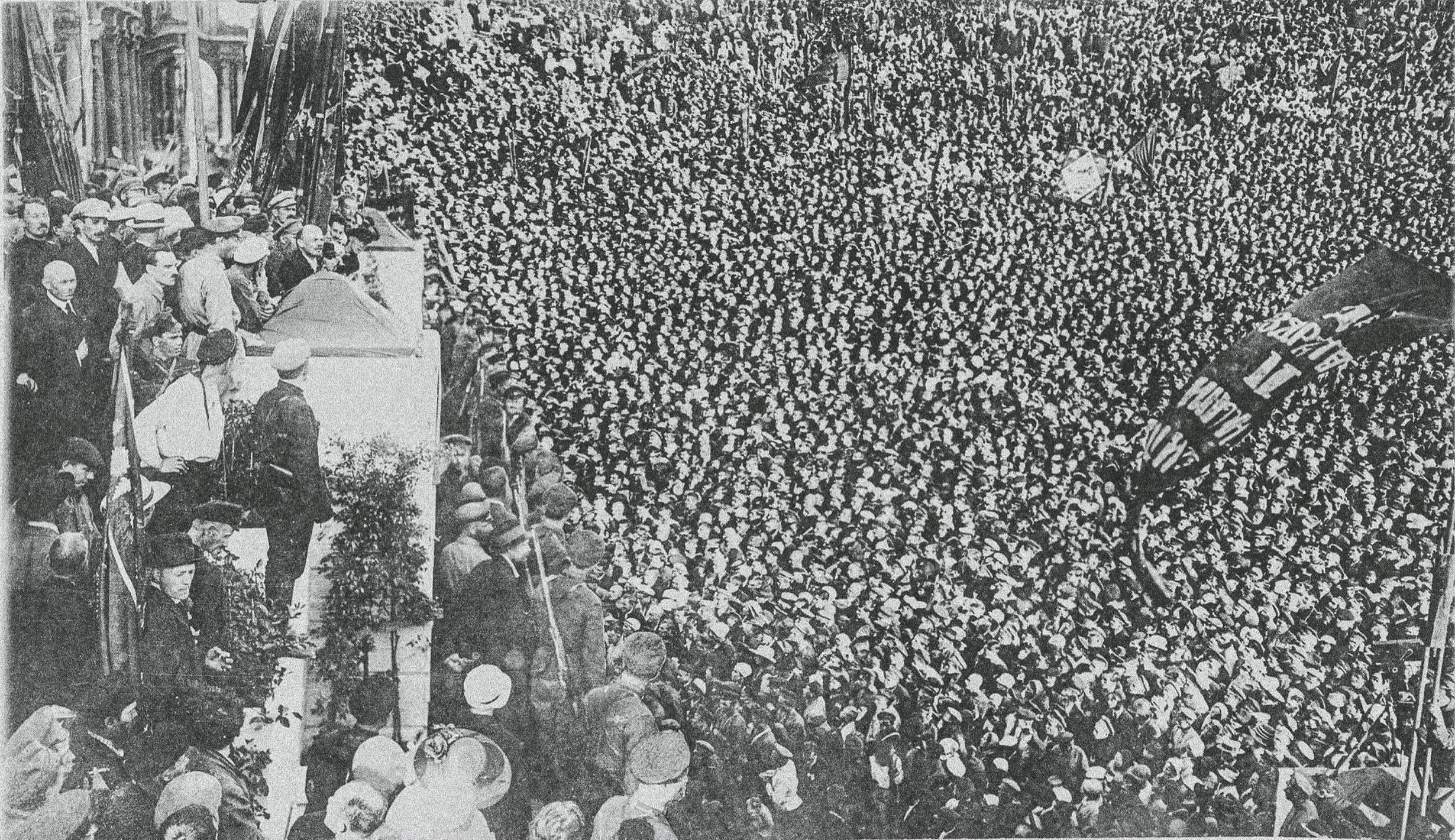

Lenin addresses a huge crowd in Petrograd at the opening of the Second Comintern World Congress in July 1920.

Preface

Some political leaders, democrats as well as dictators, each of them a striking personality, obviously leave a big mark on history. But what brings strong personalities to power? And what promotes, or limits, their use of that power? What social and political conditions determine the type of power they embody and whether authoritarian or democratic leaders can flourish? How important is personality itself, both in gaining power and then in exercising it? Television, social media and journalism all elevate the role of personality into something approaching an elemental, unconstrained political force that imposes change through individual will. But are leaders, however powerful they might seem, actually restricted by forces far outside their control?

These are fundamental questions of historical analysis. But recent experience of the leadership of Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping, Recep Tayyip Erdoan and other strong leaders has perhaps given them new relevance.

Exceptional times, it could be said, produce exceptional leaders who do exceptional things often terrible things. Systemic crisis is the common factor. The case-studies of twentieth-century European leaders in this book, some dictators, others democrats, are all but one of such exceptional leaders, products of exceptional preconditions for their specific exercise of power. The one leader explored here who does not fit this pattern, Helmut Kohl, had exceptionality thrust upon him when the collapse of the Soviet bloc unexpectedly offered the opportunity to unify Germany. Until then, Kohl had been an entirely unexceptional democratic leader. His case perhaps makes the point that, under settled conditions when there is no systemic crisis, political leaders merely nudge the lever of historical change a little, driven as they are by considerations of electoral appeal and wider forces of economic, social or cultural change that they are at best only able partially to control and which they are happy to go along with. The case-studies I have chosen focus squarely on the exceptional and do not examine the unspectacular, though sometimes valuable and beneficial, actions of those European political leaders during the twentieth century who introduced partial and incremental change. Looking to more normal, less exceptional, leaders would have produced a different book. But I had to make a selection. And it is hard to deny that those I have included did in important often extremely negative ways significantly change European history.

What follows is a series of interpretative essays on the attainment and exercise of power by a number of striking political personalities. These are emphatically not mini-biographies. Each of the leaders selected has, given their importance and huge impact, naturally been the subject of many biographical studies, which have built upon a vast amount of historical research. I have leaned on these biographies and other important works related to the individuals in question. I make no claim to have undertaken primary research myself on any of these individuals, apart from Hitler, for whom I could draw on detailed work that I undertook some years ago.

Each chapter follows a similar pattern. I look first at the personality traits and the preconditions that favoured a particular type of personality, providing the potential for the leader to acquire power. I then selectively explore aspects of the exercise of that power and the structures that made it possible. Each chapter concludes with an assessment of the leaders legacy. The Introduction outlines the framework of enquiry and poses a number of general propositions about the conditions and exercise of power which are then addressed comparatively in the Conclusion. I have kept notes and references to a minimum.

This is a book about history if recent and often still painful history. Europe has moved on from the times depicted here and, with every regard for some daunting present-day problems, overwhelmingly for the better, especially if we contemplate the horrors of the first half of the twentieth century. Recent events have highlighted social and political themes racism, imperialism, slavery, gender and identity issues which have taken on new or at any rate different forms of expression than was the case in the previous century. And politics is no longer a mans world, as it once was, something much to be welcomed. Only one of the case-studies in this book is of a woman a reflection that politics in the twentieth century was very much a male preserve. No person of colour is included a reminder that European politics in the twentieth century was not just a mans world, but a white mans world. The changes in our own times are themselves an indication that forces far beyond even the most powerful political leader induce long-term social transformation.