This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1997 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2015, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

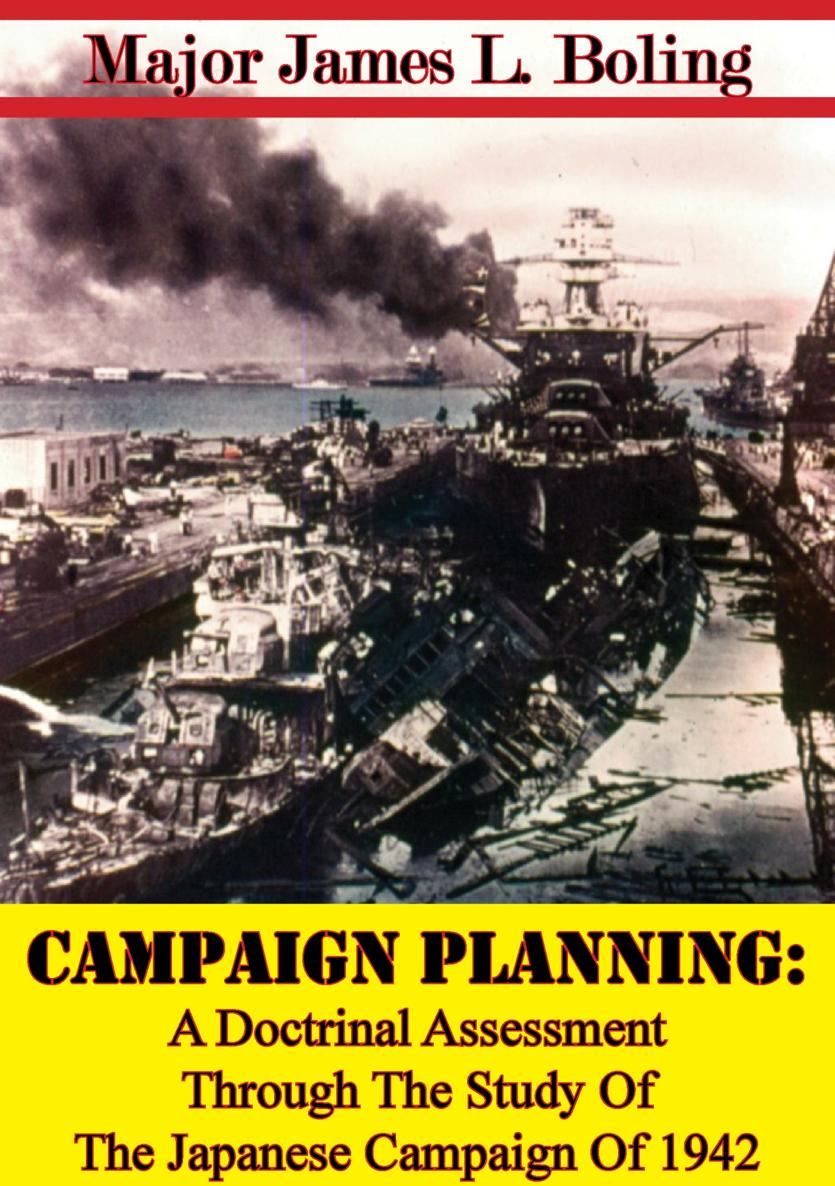

CAMPAIGN PLANNING: A DOCTRINAL ASSESSMENT THROUGH THE STUDY OF THE JAPANESE CAMPAIGN OF 1942

A MONOGRAPH

BY

Major James L. Boling Armor

ABSTRACT

This monograph assesses the adequacy of current United States joint campaign planning doctrine within the context of conventional operations between similar forces within a theater of war. The study focuses on five key doctrinal planning concepts center of gravity, decisive points, operational reach, balance, and branches and sequels.

Joint planning doctrine directly influences the national security of the United States. The foundation of effective and rigorous military planning is the body of professional doctrine that shapes and animates the planning process. The use of poor or insufficient planning doctrine may result in flawed campaign plans which unnecessarily risk the resources and prestige of the United States as well as the lives of Americas servicemen and women. Successful campaigns, developed from intellectually sound and militarily thorough planning doctrine, are the building blocks of national victory in war.

A case study of Japanese campaign planning efforts at the beginning of 1942 and the retroactive application of selected joint doctrine planning concepts to these efforts is the method and medium of inquiry. Japanese operational planning in 1942 contained a number of complex and difficult challenges. These challenges present a rigorous test for current doctrine. Historically, this process resulted in the disastrous attempt to invade Midway Island. Joint doctrine is assessed as adequate if its application to 1942 Japanese planning would have resulted in the development of a campaign plan potentially more successful than the historical Midway operation.

This paper concludes that the rigorous application of current joint doctrine by the Japanese to the planning for the 1942 campaign would have resulted in the production of a more thorough, resilient, and potentially more successful plan. Joint campaign planning doctrine, a way to think about warfare, would have overcome the challenges involved in planning this campaign.

Carried forward to our own era, this conclusion clearly indicates the adequacy of the doctrine for joint conventional campaign planning. Joint doctrine provides a sufficient conceptual framework for the design of war-winning conventional campaigns. When artfully and rigorously applied, the plans developed from this doctrine will continue to maximize and focus the United States military might in the pursuit and defense of American national security into the 21st century.

FORWARD: CENTRAL PACIFIC, JUNE 5th, 1942 {1}

I remind you that you have beaten most of the enemys fleet already; and, once defeated, men do not meet the same dangers with their old spirit. Phormio {2}

The finest theories and most minute plans often crumble. Complex systems fall by the wayside. Parade ground formations disappear. Our splendidly trained leaders vanish. The good men which we had at the beginning are gone. The raw truth is before us. GEN William ODaniel, USA {3}

Aboard the battleship Yamato IJN Combined Fleet Flagship 400 Miles Northwest of Midway Island

A terse coded message from the CinC Combined Fleet, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, was issued at 0225. Deployed across the width and length of the northern and central Pacific, individual ship captains and task force commanders of the Imperial Japanese Navy read their orders in disbelief and anguish...

(1) The Midway Operation is canceled.

(2) The Main Body will assemble the Midway Invasion Force and the First Carrier Striking Force (less Hiryu and her escorts), and the combined fleet will carry out refueling during the morning of 6 June at position 33 Deg N, 170 Deg E.

(3) The Screening Force, Hiryu and her escorts, and Nisshin will proceed to the above position.

(4) The Transport Group will proceed westward out of range of Midway-based planes.

This was a shocking pronouncement of the collapse of Japans greatest naval offensive of the Pacific War. The IJN had sortied the mightiest fleet of warships in its history for this operation. 200 ships sailed from home waters and from the southern fleet anchorages in the Marianas, including eleven battleships, twenty-two cruisers, eight aircraft carriers, and 700 combat aircraft and seasoned expert pilots. This armada was organized into six great task forces and was commanded personally by the Combined Fleet CinC Admiral Yamamoto embarked on the worlds most powerful warship, the Yamato . The fleet had steamed 2,500 miles to reach Midway, an isolated speck of sandy coral-fringed atoll 1,150 miles from Pearl Harbor at the extreme northwestern extension of the Hawaiian Chain. {4}

Here in this virtually empty quarter of the central Pacific, Japan had sought the longed for grand fleet battle which would decide the war. None had doubted the outcome of this meeting with the arch rival US Navy. After the enemys mauling at Pearl Harbor and the Coral Sea, how could the US Navys shattered remnants hope to stand against the power of the Imperial Japanese Navy? Victory seemed simply a matter of time and opportunity. {5}

Now what had begun so expectantly less than 48 hours ago lay in ruins {6} . Airfields on Midway and their aircraft were damaged but operational and the US Navy now had a powerful force, including two to four fleet carriers, concentrated somewhere northeast of Midway. Meanwhile, Japanese losses were staggering. Four first-line carriers and a heavy cruiser were sunk or sinking, a second heavy cruiser and two destroyers damaged, 234 combat aircraft and irreplaceable pilots lost, and 2,200 crewmen killed. While the striking power and morale of the Combined Fleet were being sent to the bottom, and with them the Japanese initiative in the Pacific, Yamamoto and his staff had remained isolated and impotent aboard the Yamato hundreds of miles from the action.

Now fully aware of the magnitude of the disaster, the frustrated staff officers were anxious to avenge their humiliation. Several fantastic, almost suicidal, schemes were proposed for continuing the action and rescuing at least some degree of honor from the ashes. These were curtly vetoed by Yamamotos ruthlessly pragmatic Chief of Staff, Admiral Ugaki. {7}