www.upress.state.ms.us

The University Press of Mississippi is a member of the Association of University Presses.

Copyright 2018 by University Press of Mississippi

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing 2018

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ramsaran, Dave, author. | Lewis, Linden, 1953 author.

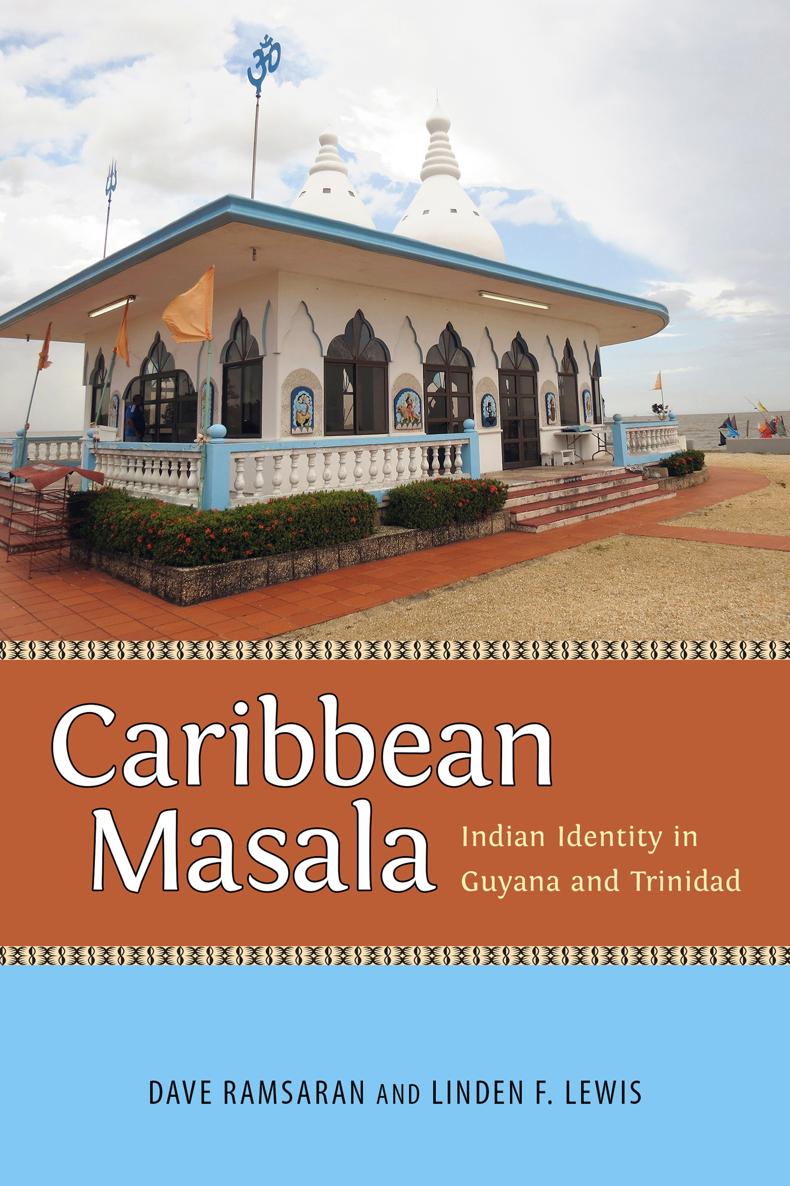

Title: Caribbean masala : Indian identity in Guyana and Trinidad / Dave Ramsaran and Linden F. Lewis.

Description: Jackson : University Press of Mississippi, [2018] | Series: Caribbean studies series | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Identifiers: LCCN 2017058597 (print) | LCCN 2018000677 (ebook) | ISBN 9781496818058 (epub single) | ISBN 9781496818065 (epub institutional) | ISBN 9781496818072 (pdf single) | ISBN 9781496818089 (pdf institutional) | ISBN 9781496818041 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Group identityCaribbean Area. | East IndiansTrinidad and TobagoTrinidadHistory. | East IndiansGuyanaHistory.

Classification: LCC F2191.E27 (ebook) | LCC F2191.E27 R37 2018 (print) | DDC 972.9/004914dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017058597

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

Introduction

Masala is a Hindi word that refers to mixed spices. At one level, the word is used in the title of this book as a metaphor not only for the Indo-Caribbean communities of Trinidad and Guyanathan twelve thousand years. Today, there are nine existing indigenous groups in Guyana accounting for 7 percent of the population.

Caribbean Masala, then, focuses on the ambivalent processes of mixing, assimilating, and adapting on one level, while trying desperately to hold onto that which marks a group of people as distinct, different, and somewhat separate. The lived experience of the Indian community in Guyana and Trinidad in some ways represents a cultural contradiction of belonging and nonbelongingof being a part of all that is the Caribbean yet not wanting to belong so completely as to be overwhelmed by the dominance of the African presence in the Caribbean, which confronts them on all levels.

In this work, we settle on the terms Indian, Indian descent, and Indo-Trinidadian or Indo-Guyanese. We have shied away from the term East Indian, which was used largely because of Columbuss mistaken belief that he had reached the East when in fact he had arrived in the Caribbean, and so the term was based on a misconception. In addition, the term East Indian tends to be used as a way to distinguish people of Indian descent from those who are directly from the subcontinent. Indians from India are not only seen as more authentic genealogically than their Caribbean descendants, but are also viewed as culturally different from the Indo-Caribbean people of Guyana and Trinidad. We are, however, fully cognizant that the use of the term Indian does not resolve all definitional problems, as the writer V. S. Naipaul (2003, 39) reminds us: To be an Indian from Trinidad is to be unlikely. It is, in addition to everything else, to be the embodiment of an old verbal ambiguity. For this word Indian has been abused as no other word in the language; almost every time it is used it has to be qualified. Of course, there are somewhat less grave social consequences, which are captured in an exchange between Naipaul and a fellow traveler waiting for a flight from London to Paris:

You are coming from?

I had met enough Indians from India to know that this was less a serious inquiry than a greeting, in a distant land, from one Indian to another.

Trinidad, I said. In the West Indies. And you?

He ignored my question. But you look Indian.

I am.

Red Indian? He suppressed a nervous little giggle.

East Indian. From the West Indies.

He looked offended and wandered off to the bookstall. From this distance he eyed me assessingly. In the end curiosity overcame misgiving. He sat next to me on the bus to the airport. He sat next to me in the plane. (2003, 35)

It should be noted at this point that the numbers of people of Indian descent in Guyana and Trinidad are significantin fact, Indians outnumber all other groups in both countries, with 39.9 percent and 35.4 percent, respectivelythe only other country where Indians exist in such significant numbers being Suriname (37 percent). In other parts of the Caribbean, Indians are not as demographically strong. In places such as Martinique (10 percent), Saint Lucia (2.2 percent), Saint Kitts and Nevis (1.9 percent), and Grenada (0.4 percent), people of Indian descent are often so absorbed into the more dominant African culture, and through marriage to non-Indians, that the issue of an Indo-Caribbean sense of heritage figures only peripherally in national discourses on identity. This observation prompted V. S. Naipaul to observe:

Growing up in multiracial Trinidad as a member of the Indian community, people brought over in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to work the land, I always knew how important it was not to fall into nonentity. In 1961, when I was traveling in the Caribbean for my first travel book, I remember my shock, my feeling of taint and spiritual annihilation, when I saw some of the Indians of Martinique, and began to understand that they had been swamped by Martinique, that I had no means of sharing the world view of these people whose history at some stage had been like mine, but who now, racially and in other ways, had become something other. (1989, 33)

Amartya Sen describes this cultural erosion as identity disregarda form of ignoring, or neglecting altogether, the influence of any sense of identity with others, on what we value and how we behave (2006, 20). While certain Indian rituals and customs persist in parts of the Caribbean, they do not always constitute a central or dominant part of the identity of those who perform them. Naipauls comments are a reflection of the time and perhaps his own narrow reading of people of Indian descent in Martinique. There is a greater interest in matters of identity and heritage in the contemporary French Caribbean than there was when Naipaul was writing about the region.