Copyright Andrea Mariuzzo 2018

The right of Andrea Mariuzzo to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Published by Manchester University Press

Altrincham Street, Manchester M1 7JA

www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 5261 2187 5 hardback

First published 2018

The italian version Divergenze parallele: Comunismo e anticomunismo alle origini del linguaggio politico dellItalia repubblicana (19451953) (ISBN 9788849825169) has been published by Rubbettino Editore. The book has been published with the contribution of Scuola Normale Superiore, Pisa.

The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for any external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Typeset by Out of House Publishing

Basically there was only one problem, and they were completely agreed about it: to restore the authority of the State They were ready to make every concession for this, although in different degrees. Colombi talked in a lukewarm fashion of reforms. Tempesti, when it was his turn, wholeheartedly professed a reverence for the religious beliefs of his colleague. The crisis [of government] might prove useful, a good step along the road to normality. It didnt matter, although it was obvious, that to each this meant something different. The expression was the same and all that really mattered was that it should seem identical.

In The Watch, Carlo Levi imagined this conversation between two prominent members of the broad anti-Fascist coalition governing Italy at the end of 1945: the ministers Tempesti (a fictional version of the Communist Emilio Sereni) and Colombi (representing Attilio Piccioni, an influential member of Christian Democracys conservative wing). Responding to the resignation of Ferruccio Parris government, which Levi saw as an end to the hopes for a profound renewal of Italian society that had inspired the Resistance, two groups at opposite ends of the Italian political spectrum were using the same vocabulary and expressing themselves in the same way. While their ideas were certainly very different, and their goals increasingly so, the words they used in common showed that these political opponents shared an understanding of what was meant by government.

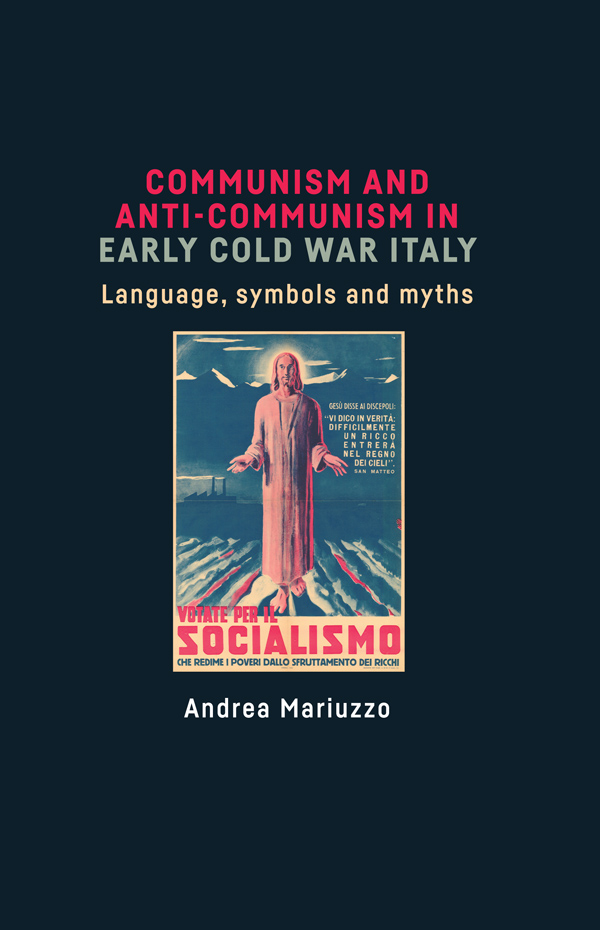

Levi was an attentive observer of Italian politics, and when writing these pages in 1950 he must have been aware that within the space of a few years these similarities in linguistic usage had been profoundly affected by changes in the political climate; language had in fact been transformed from a medium of understanding between adversaries into an arena of bitter conflict. One of the most distinctive aspects of Italian political communication during the most difficult years of the Cold War can be seen in the parties employment of very similar terms and key concepts, with the aim of acquiring a monopoly of their correct usage while suggesting that their adversaries were usurpers whose discourse was mistaken and misleading. Both the Italian Communist Party (PCI) and its detractors identified with the adjective democratic, and proclaimed the need to defend the fundamental guarantees of the Constitution from their opponents. Both sides claimed ownership of the symbols on which the identification of Italians with their fatherland had been established, and each accused the other of acting for foreign powers. Both the Communists and anti-Communists promoted their programmes as the only way of defending the universally desired peace, which their opponents sought to destroy by leading the world into a new war. The political programmes of both the PCI and the centrist forces in government were presented as the unique means of guaranteeing economic development and achieving wellbeing throughout society, as against the plans of their opponents which would only lead to abject poverty. In the sphere of political language, at least, the affirmation and defence of the traditional Christian spirit was a point of reference not only for those aligned with the Church, but also for representatives of the Marxist Left.

It could be argued, in line with Pocock, that the various political forces were simply using the conceptual vocabularies that were available. In the wake of centuries of Catholicism embedded in social life, decades of Risorgimento mythology, the horrors of a war that nobody wished to see repeated, and finally the victory of the language of freedom and democracy that followed the downfall of Fascism, any political force seeking legitimacy in Italian society had no choice but to use this same language. It was introduced into opposing channels of communication that had of course been developed within completely different ideological frameworks.

This thinking can be further developed with reference to Angelo Ventrones formulation, in which neither the Communists nor the anti-Communists recognised the right of their enemy within to citizenship, understood as full membership of a community. Each political party ended up insisting blindly on its role and presenting itself as the unique vehicle for the genuine interests of the national community, and for proper civic virtues: that collection of attitudes which provided the basis for peoples way of life and their involvement in the fortunes of their community.

New avenues for understanding the nature of Italys political system in the post-war period can thus be opened up by analysing the language that was developed around key terms by the political forces facing each other in the battle between Communism and anti-Communism, and by investigating the processes whereby republican citizenship was developed and strengthened. This book offers solutions to some of the interpretative problems in this field, focusing its attention on a period of major conflict in Italian democratic life: this started with the exclusion of the PCI and the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) from the government in May 1947, and came to an end with the elections of 7 June 1953. At this latter point both sides were forced to change their approach in the wake of the succession to Stalin, on the international front, and the internal backlash against the