Rebellious Cooks and Recipe Writing

in Communist Bulgaria

To Lode Desmet, who brings me coffee in bed every morning and lets me be myself

To Elena Shkodrova, who sometimes started cooking at 4 AM

To Yana, Elena-Mie and Artuur, who kept this book concise

Food in Modern History: Traditions and Innovations

Series Editors

Peter Scholliers

Amy Bentley

This new monograph series pays serious attention to food as a focal point in historical events from the late 18th century to present day.

Employing the lens of technology broadly construed, the series highlights the nutritional, social, political, cultural, and economic transformations of food around the globe. It features new scholarship that considers ever-intensifying and accelerating tensions between tradition and innovation that characterize the modern era. The editors are particularly committed to publishing manuscripts featuring geographical areas currently underrepresented in English-language academic publications, including the Global South, particularly Africa and Asia, as well as monographs featuring indigenous and under-represented groups, and non-western societies.

Forthcoming

Food and Aviation in the Twentieth Century: The Pan American Ideal, Bryce Evans (2021)

Albena Shkodrova is a historian and a writer. After a career in political journalism, she worked as a travel writer and was for eight years the editor in chief of Bulgarias food and wine magazine Bacchus. She is the author of the popular book Communist Gourmet (2014), a bestseller in Bulgaria, and of popular and academic articles on social history of food and everyday life, published in Gastronomica, Food, Culture and Society, Food and History, and Appetite. She has been a member of the research groups Social and Cultural History of Food (FOST) and Modernity and Society 18002000 (MoSa) in Belgium and is currently a researcher at the Centre for Social Movements in Bochum, Germany.

Contents

I am deeply beholden for advice and support to Peter Scholliers of the Free University of Brussels and Yves Segers of the KU Leuven. Without their trust in this project, this book would not have been possible.

All across Bulgaria, people generously shared with me their time, life stories, recipes, and often food, for which I am greatly indebted: warm gratitude to Arie Babechka, Bozhurka Velkova, Cathy Ivanova and Neva Mitcheva, Danieka Lyubenova and Lyubka Georgieva, Danya Lam, Dobrinka and Presian Boevi, Ekaterina and Atanaska Terzievi, Elena Salmadzhiyska, Elisaveta Shkodrova, Fatme Ali, Kristin Razsolkova, Lilia and Daniela Denchevi, Mara Tseneva, Maya and Violeta Kaloferovi, Maya and Vasilena Mirchevi, Nedyalka Malcheva and Pepa Peneva, Olga Nikolova, Pepa Mutafchieva, Petya and Yordanka Tsachevi, Silvia and Ivanka Atipovi, Sofia Panayotova-Beneva, Sofia and Veselina Georgievi, Svetoslav Pintev and Vanya Pinteva, Tamara Ganeva, Tsveta Tanovska, Velichka Hristova and Kalina Kechova! I will always perceive the hours, spent with them, as a privilege.

This book has benefitted greatly from the inspiring conversations with, and insightful remarks and encouragement from Martin Kahlrausch, Rayna Gavrilova, Ruth Oldenziel and Paul Erdkamp. I owe much to Iva Rudnikova and Economedia for setting me on the path of investigating the social history of food and supporting for many years my work for Bacchus our encounter so many years ago was one of the happiest happenstances in my life.

Thanks to Nikola Mihov and Nikolay Grigorov of Raketa, Fabrika Duga and Cosmos in Sofia for their enthusiastic support of my work on Bulgarian communist food, and for the means and time they invested in supplying visual material for my several projects.

This book would not have materialised without the warm and kind support which my husband Lode Desmet has always given me. I particularly appreciate that despite his many and brilliant film projects, his tight schedules and stressful periods of intense work, he has always found a way to give me space and time to work and be who I am: so this book is dedicated to him. I also dedicate it to the memory of my mother Elena Shkodrova, who is responsible for my earliest memories of communist cooking and cuisine. To my children Artuur, Elena-Mie and Yana this book owes its conciseness!

Albena Shkodrova

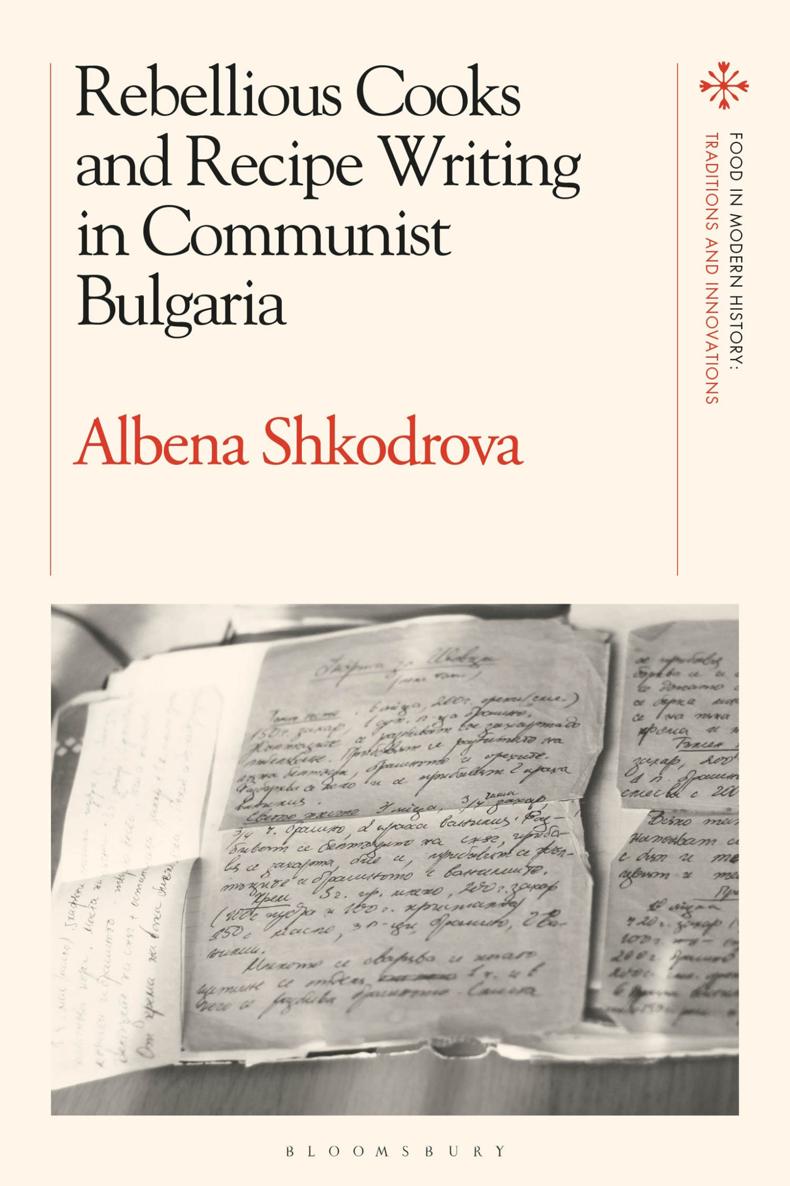

In 2012 a friend put a book in my hands a kind of book I had never seen before. It was a volume the size of a standard A4 sheet, with hard covers, bound in blue cloth and with faded golden letters that read Cooking Recipes. I knew straight away that it was a samizdat book: it had the typical appearance that the book-binders in one of the small streets off Klement Gottwald boulevard in Sofia in the 1980s gave to everything from a masters thesis to a collection of valued magazines. But I had never seen a cookbook made this way.

Opening it brought further surprises. Just like a printed book, it had a title page, on which Gotvarski retsepti (Cooking Recipes) was typewritten, followed by a dedication in handwriting: And dont forget the old saying that Love passes through the stomach. Then followed a table of contents: fourteen sections, dedicated to generic categories (starters, soups and mains) or more specific groups of dishes (jellies, cookies, biscuits, buns, pastry and others, juices, cakes, rolls and parfaits), with several sheets of Useful advice at the end. There were 115 pages, most of which were typewritten and the rest were clippings from the press.

Consumed with curiosity, I arranged a meeting with my friends mother, Cathy Ivanova. A Sofianite in her 70s, she spoke sophisticated Bulgarian and had the air of modesty and slight insecurity in social interaction typical of her generation which is also the generation of my mother. Cathy Ivanova told me that she had made three copies of the book for her family. Some of her colleagues also made facsimiles, and as this happened on several occasions, in the end she lost track of how many times her book was reproduced.

To me she gave two folders: one, containing the recipes as they were typed, written, collected through the years, and the other with the laid out pages, which were used as a prototype for all the further copies. They were numbered A4 sheets with typewritten recipes or glued-on clippings.

My acquaintance with this astonishing work came during a broad research project on food under communism (Shkodrova 2014), which later brought me to another avid collector of recipes, Tamara Ganeva. Slightly younger than Cathy, Tamara had left Bulgaria in the 1990s and had settled in Paris with her husband, the painter Valentin Ganev. In September 2012 I met her in a caf in Brussels: she had come to visit one of her daughters, who studied there. Similarly to other Bulgarian immigrant women from her generation, Tamara had fashioned a specific style that combined the homeliness of a Bulgarian housewife, as I knew it from my childhood, with a certain worldliness and elegance. She clearly felt at home in the arty chic of the Brussels caf something that would hardly have been the case for her schoolmates still living in Bulgaria.

Some time into our conversation Tamara opened her bag and took out a sheet of self-adhesive sticker paper, on which she had written a recipe. She explained that she had a personal collection, of which she kept three copies one for herself and one for each of her daughters, who already lived independently. As she kept adding content to her scrapbook, she also offered it to her children the sticker paper was aimed to occupy a new page in the scrapbook of her daughter living in Brussels.