2021 Georgetown University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

The publisher is not responsible for third-party websites or their content. URL links were active at time of publication.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Grassi, Giovanni, 17751849, author. | Severino, Roberto, translator.

Title: Georgetowns Second Founder : Fr. Giovanni Grassis News on the Present Condition of the Republic of the United States of North America / Roberto Severino, Translator.

Other titles: Notizie sullo stato presente della repubblica degli Stati Uniti dellAmerica Settentrionale, scritte al principio del 1822. English | Fr. Giovanni Grassis News on the present condition of the Republic of the United States of North America

Description: Washington, DC : Georgetown University Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020008157 | ISBN 9781647120436 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781647120443 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Grassi, Giovanni, 17751849TravelUnited States. | United StatesDescription and travel. | United StatesReligion.

Classification: LCC E165 .G7613 2021 | DDC 973.5/4dc22

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020008157

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

22 219 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 First printing

Printed in the United States of America.

Cover design by Erin Kirk

Text design by Classic City Composition

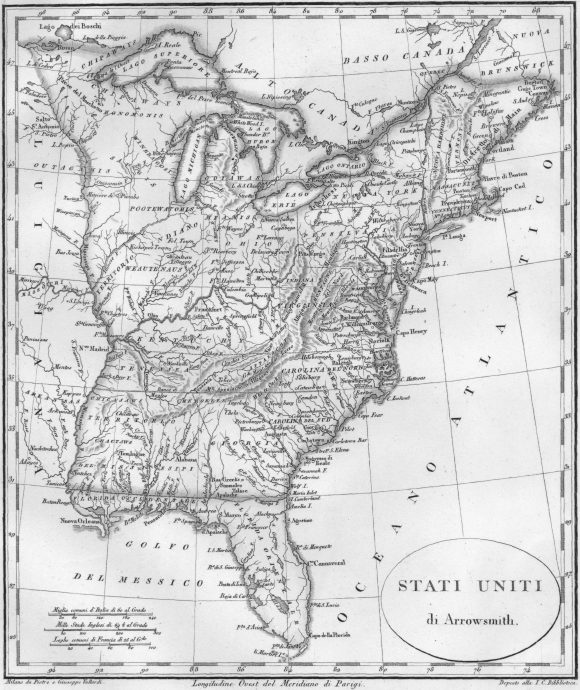

The folio features an undated Italian version of a map of the United States by the eminent geographer and cartographer Aaron Arrowsmith. Sold in Milan by the Giuseppe and Pietro Vallardis firm, ca 181215.

Tempo verr, che fien dErcole i segni

Favola vile a naviganti industri,

E i mar riposti, or senza nome, e i regni

Ignoti ancor tra voi seranno illustri.

GERUSAL. LIB., canto xv st. 30

The time shall come that sailors shall disdain

To talk or argue of Alcides streat,

And lands and seas that nameless yet remain,

Shall well be known, their boundaries, site and seat

FROM Torquato Tassos (15441595) Gerusalemme Liberata (Jerusalem Delivered), Canto XV, first four verses of stanza 30, rendered in English in 1600 by Edward Fairfax (15601635). Alcides Streat refers to the Pillars of Hercules, the two promontories flanking the Strait of Gibraltar.

FOREWORD

I N THE SHAPING of the Catholic Church in the early American republic, immigrant clergy and religious played a disproportionately huge role. Perhaps never have so few had such influence in developing the institutional matrix and culture of the American Catholic community, from Boston to New Orleans, and from Baltimore to Saint Louis. Most were French migrs, such as Ambrose Marchal, Jean Lefebvre de Cheverus, Benedict Joseph Flaget, John Dubois, Philippine Duchesne, and Louis William Dubourg. But other Europeans left their lasting imprint as well, notably John England of Ireland and Joseph Rosati of Italy. Another Italian, Giovanni Grassi, unlike the others, spent barely seven years in the United States. In that brief period, nonetheless, Grassi left his permanent mark on the first Catholic college in the United States by saving it as an educational institution and by establishing important relations between the college and the federal government. Despite his short sojourn here, he was a keen observer of the culture and economy of the young republic in the third decade of its history, as he well demonstrated in Notizie varie sullo stato presente della repubblica degli Stati Uniti dellAmerica settentrionale scritte al principio del 1818 (1819). Grassi, in fact, was the only one of this distinguished immigrant cohort to publish his impressions of this country, which makes Notizie all the more special.

A native of Bergamo in northern Italy, Grassi had entered the Society of Jesus in 1799, when the order was still under papal suppression, except for the Byelorussian territories of eastern Poland and Lithuania, which were under the control of Catherine of Russia. The Russian ruler, valuing the Jesuit schools within her jurisdiction, had refused to allow the promulgation of the brief of suppression. Grassis Jesuit superiors, recognizing his extraordinary intellectual and administrative talents, had expedited his training and, after his ordination in 1805, appointed him rector of a college in Russian Poland. Scarcely had he begun his tenure when he was named to a three-man mission to China. For five years he made various attempts to find a port from which to make his passage to Asiaall in vain. In the meantime, at the Jesuit college in Stonyhurst, England, he pursued studies in mathematics and astronomy. Finally, in 1810, the Jesuit superior general changed Grassis mission from China to the United States, where some ex-Jesuits had recently rejoined the Society that survived in Russia.

Less than a year after he arrived at Georgetown College, Grassi was given a dual appointment: rector of the college and superior of the Maryland Mission. He found the college to be in a miserable state, with crushing debts and few students (blackguards, Grassi deemed them). Georgetown, he wrote an English Jesuit in 1811, was unlike any Jesuit college he had ever known, and he hoped never to know another such one. Whereas Georgetown had, until recently, attracted students from all parts of the country as well as from Central America, now the college was losing them to colleges in Baltimore and New York, operated by Sulpicians and Jesuits, respectively.

Of immediate concern to Grassi was his legal authority as rector and superior. Legally, the college belonged to the Corporation of the Roman Catholic Clergymen of Maryland, an autonomous, self-perpetuating body, created in 1792 to protect the lands previously owned by members of the Society of Jesus before its suppression. The trustees of the corporation appointed the directors of the college, who elected its rector. Grassi effectively had to use all his considerable diplomatic and administrative skills to govern the college within this Byzantine organization, largely by coaxing the directors and trustees to go along with his plans for the college and mission. First was his audacious proposal to virtually halve the cost of boarding at Georgetown, from $220 to $125, to increase enrollment. Similar adjustments were made for commuting students. But financial adjustments alone could not save Georgetown. The faculty was barely a faculty at all, with but one priest (besides Grassi) and three scholastics (seminarians). If Georgetown was to be a college in more than designation, it needed more professors to offer a full curriculum ranging from the classics to philosophy. A consolidation of the Jesuit educational institutions in Washington and New York was the only solution to their manpower shortage. So in 1813, Grassi, with Archbishop John Carrolls backing, recalled the Jesuits teaching in New York, which drew vehement protests that they were abandoning a school in what was becoming the most important city in the country, making it fifty times more valuable than Georgetown. Grassi, focusing on the present crisis rather than any future promise, persisted.

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.