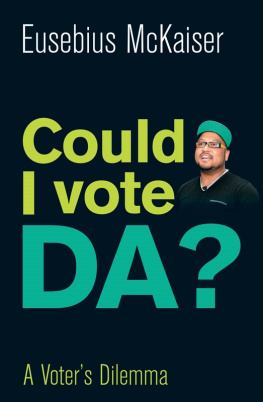

COULD I VOTE DA?

A Voters Dilemma

Eusebius McKaiser

Text Eusebius McKaiser, 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission from the copyright holder.

ISBN: 978-1-920434-55-7

e-ISBN: 978-1-920434-56-4

Published by Bookstorm (Pty) Ltd

PO Box 4532

Northcliff 2115

Johannesburg

South Africa

www.bookstorm.co.za

Edited by Sharon Dell

Proofread by Sean Fraser

Cover design by mr design

Book design and typesetting by Triple M Design

Ebook by Liquid Type Publishing Services

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Confessions of a confused voter

O n the 18th of May 2011, I woke up to a beautiful autumn morning in my flat in bohemian Melville, Johannesburg. It was quiet outside; no trace of Mandelas born-free generation who revel here at night-time. There was another reason, however, for this particular days early-morning tranquility. It was a public holiday, and thats always reason for self-declared overworked South Africans to sleep in before turning their attention to the braai. Or, at least, that was my fear. Fear because the public holiday was actually the occasion of the local government election. Commentators had pretended to be sangomas with predictive powers, and many asserted that voter turnout would be low. As I left my apartment to go and vote in Sandton (where I had lived before), the silence that enveloped me outside seemed to vindicate the sceptics. But, it was still early.

As it happened, it was a hugely successful election from a voter turnout perspective some 57.6% of registered voters cast their ballots, in enviable contrast to many democracies around the world that often have local election voter turnouts below 40%. So much for the assumption that dissatisfaction with service delivery would lead to black African voters in particular staying away from the polls in non-violent protest.

I was up early because I had to vote early. I was due to cover the elections for a television station as one of its rotating studio anchors, so would not have time to stand in a voting queue later. As the cab made its way from Melville through Parktown North, Rosebank, and from there to Sandton via Illovo, a single thought preoccupied my 32-year-old head. Who should I vote for, I wondered? I had still not made up my mind. I had two votes up for grabs, one for the proportional representation candidate from a party in whose ideas I had faith, and one for a directly elected ward candidate (on the basis of the first-past-the-post yardstick). I had no clue who to vote for. No clue.

For years I found the basic policy positions of the African National Congress (ANC) compelling. The party supports the idea of a welfare state, which I am grateful for as a first-generation black graduate who inherited the burden of having to send remittances home to poor family members. I have seen poverty. I have experienced it. And I have, more importantly, witnessed the social context in which poor peoples agency remains undeveloped. A tough-love approach to poverty just does not sit well with me emotionally. My underperforming siblings did not choose, in any straightforward sense of the word, to drop out of school, and to have teen pregnancies. So I am grateful that a social security system is in place to ensure their kids dont starve during a month that Uncle Eusebius is unable to top them up. The ANC gets this.

And, in addition, the ANC understood very quickly after democracys birth that the world is governed by a neo-liberal economic framework. The principles of neo-liberal economics are many and complex. The basic philosophical change the ANC had to make and did (in no small part due to the hard work of that famous Aids denialist but reasonably gifted economics graduate, one Thabo Mbeki) was to let go of socialist-inspired ideas of heavy state involvement in the economy and to accept that markets are fairly efficient mechanisms for allocating resources, determining where supply and demand should settle, what wage levels are economically sustainable, etc. In practical terms, this meant abandoning policies like the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP), and settling for investment-friendly, growth-conducive policies that would hopefully still generate jobs.

Of course, many left-leaning economists will remind us of the jobless growth years during Mbekis time in office. The point simply is that one would be unkind and frankly wrong to characterise the ANC as failing to choose a macroeconomic framework consistent with a world in which market-based economic activity had won the ideological battle against communist, command-based systems.

And, when it comes to social policies to do with lifestyle and identity issues, I was happy with the ANC too. Of course there are homophobes and sexist pigs in the ANC. That has to be the case in any big party that attracts members and supporters from across society. And yet the ANC leadership (or most of it) was happy to toe the liberal line when it mattered . The ANC, for example, gave their MPs no choice in 2006 but to vote in favour of the Civil Unions Bill which extended marriage rights to gay couples. They did not allow MPs to vote according to conscience, as the Democratic Alliance did in a fit of illiberalism.

The ANC placed a higher premium on substantive equality for gay and lesbian South Africans than on the personal beliefs about homosexuality that might be lurking in the hearts of MPs. The ANC, similarly, never used its parliamentary majority to undo very liberal positions on the death penalty, corporal punishment and other social issues that flowed from Constitutional Court judgments.

This is not to say I am overly grateful that the ANC is doing what it ought to do anyway, which is respect the standards that we as a society chose to be bound by legally and constitutionally. But as someone deeply committed to the ideal of a liberal society, I was comfortable with the ANCs nominal, if not always heartfelt, support of liberal social policies. The ANC ultimately accepts, even if sometimes grudgingly, that individual autonomy should not be sacrificed in the name of populism.

And so, as I was on my way to vote that morning, I found it tempting to reward the ANC for policies and ideologies that resonate deeply with my personal experiences, with my familys desperate situation back in Grahamstown, and with my commitment to liberalism.

And yet I wasnt sure I could actually get myself to vote for the ANC. Given how endemic corruption has become in the state under successive ANC governments, the gap between the policy ideals and delivery was (and still is) big and growing. Commentators predictions of poor voter turnout werent misplaced, even if they turned out to be false: the daily experiences of millions of South Africans remain that of being marginalised and effectively disenfranchised. Worse, there was (and is) an unsettling arrogance and political entitlement that too many ANC politicians and ANC-appointed government officials display.

I found myself wondering, Eusebius, do you really want to reward the arrogance of so many underperforming, ethically wayward ANC politicians? Do you? I could not honestly answer in the affirmative. Not with a clear conscience, anyway. After all, as much as I enjoy policy and ideological debates, these are irrelevant if peoples lives dont really change. Not to mention that by that time I had met and engaged plenty of tripartite alliance politicians whose gigantic egos and sense of entitlement had left a bad taste in my mouth.

Next page