MAO AND MARKETS

MAO AND MARKETS

THE COMMUNIST ROOTS OF CHINESE ENTERPRISE

CHRISTOPHER MARQUIS

AND

KUNYUAN QIAO

Copyright 2022 by Christopher Marquis and Kunyuan Qiao

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Sabon by Westchester Publishing Services.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022942198

ISBN 978-0-300-26338-1 (hardcover: alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

For Alex and Ava and their generation as they navigate the complex relations between the worlds most powerful countries.

CHRIS

For my family as they are concerned with and hoping for better U.S.-China relations.

KUNYUAN

Contents

MAO AND MARKETS

Introduction

CHINAS SPECTACULAR ECONOMIC GROWTH over the past four decades bears stark witness to the power of markets. Between 1978when China began its economic reformsand 2019, Chinas annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate averaged 9.45 percent, while its GDP per capita grew an astonishing sixtyfold.

Thanks to these and other achievements, starting in 2017, the US National Security Strategy began referring to China as a primary strategic competitor.

Underlying this policy confusion, Chinas rise calls one of capitalisms most cherished beliefs about itself into question. Free markets are widely presumed to be more efficient than state-controlled economies and thus make the latter obsolete; moreover, they are thought to promote freedom in other spheres of life. Following traditional economic development theory, many people, including top China strategists in the White House, predicted that Chinese president Xi Jinping would push for economic reforms such as privatization of state-owned enterprises when his administration began in 2012.

In recent years Xi has urged all private companies to serve the state, extolling the patriotic entrepreneur Zhang Jian, who did so in the Qing dynasty; sent Chinese Communist Party (CCP) representatives to private firms; suspended the initial public offering of Ant Financial (the largest payment platform in China, owned by the Alibaba Group); made it increasingly hard for Chinese companies to list on US stock markets; and asked state entities to take stakes and board seats in important technology companies such as ByteDance (owner of TikTok), Sina Weibo (the most popular microblogging website), DiDi (the largest ride-hailing company), and others.

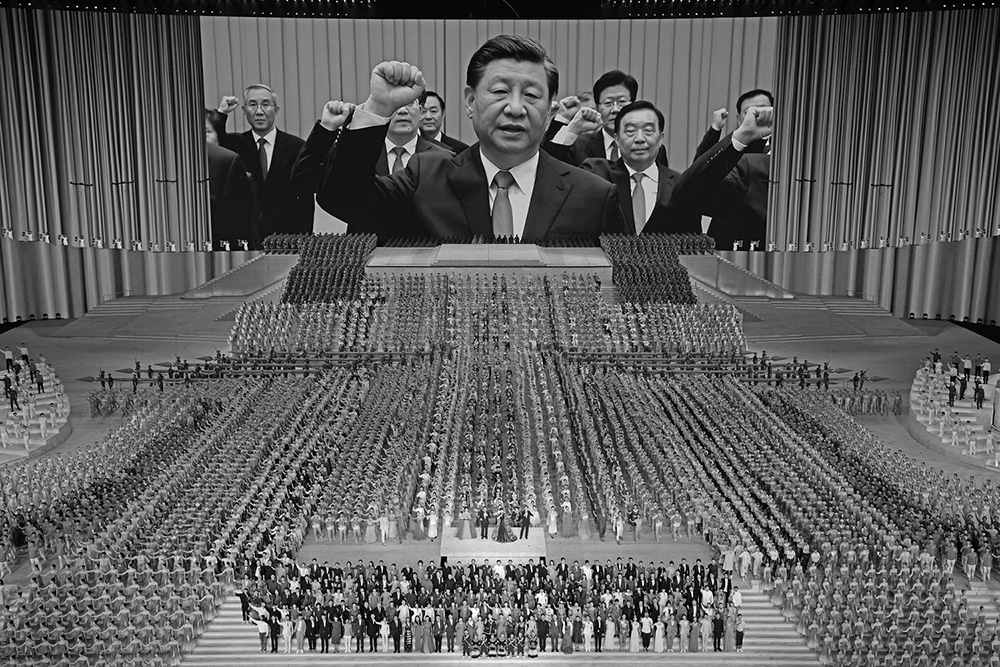

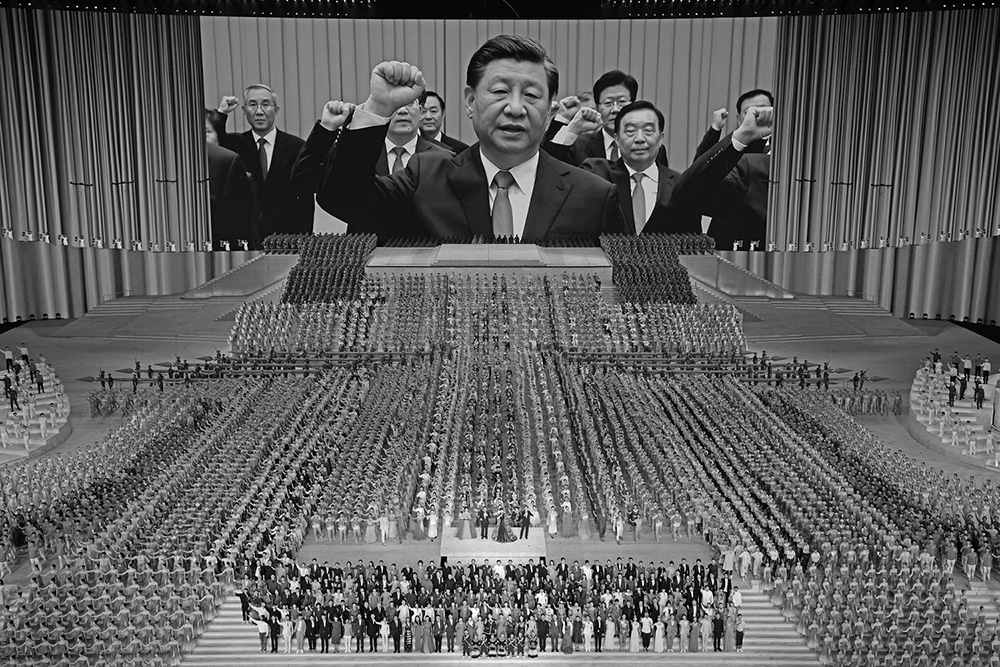

During the centenary celebration of the CCP on July 1, 2021, Xi doubled down on Chinas commitment to communism, commenting that any attempt to separate... the CCP from the Chinese people will never succeed! He also emphasized the importance of one-party rule and In figure I.1, Xi leads senior political leaders in revisiting the CCP oath as part of the centenary celebrations.

Figure I.1 President Xi Jinping Leads Politburo Members in Renewing Their CCP Vows during the CCP Centenary Celebration

China Crackdown, Associated Press, June 28, 2021. AP Photo/Ng Han Guan.

Overall, Xi seems to have pulled China from decades of Western-style capitalist reform and embarked on a new path with heavy state intervention (for example, in 2021, the CCP-government issued more than a hundred regulations, including ones that targeted large private businesses), more equal distribution of wealth (for example, a policy called common prosperity that some see as robbing the rich), and stricter CCP control, all of which revisit the socialist version of the economy of his founding counterpart, Mao.

Behind all these puzzling facts are questions about what kind of regime China is: a Marxist-Leninist state, a digital authoritarian country, a crony capitalist nation, or something else? It has gradually become

Related to these hardened ideological stances, there has been too much wishful thinking about the CCPs future and overall an unrealistic imagination of life on the ground in China. Many people believe communism will collapse in China, as happened in the Soviet Union and other Eastern European countries three decades ago. These observers may have overestimated the liberalizing power of the marketplace and how much the United States and the West in general can affect Chinas domestic and foreign policies. As the foregoing examples suggest, Xi is committed to developing a model for China that is independent of the West.

Since the United States and China are the worlds largest economies and most important national actors, we believe that realistic engagement is essential for both countries and for the world at large, especially given the recent concerns about decoupling (for example, in the technology and financial realms) and even discussion that we may be entering By realistic, we mean that the hard calculus of national interest should drive engagement. But to accomplish this, analysts and policymakers have to start with a more accurate and objective evaluation of China, rather than just relying on politics and empty hopes. To do so effectively, we are in dire need of more accurate knowledge of Chinas deeply seated ideology.

Many China commentators have focused on Chinas ideological flexibility in incorporating capitalist elements into its state-run economy since its opening in 1978 and are surprised when there are reversions as have occurred under Xi. Our alternative view is that it is not a question of what has changed, but how it has and, even more importantly, what has remained the same. As we show in more detail, Mao, the powerful founder of the Peoples Republic of China, has left an enduring imprint on Chinese individuals, society, and institutions that even today strongly shapes Chinas economic and political activities. While there may be changes, or periods of flexibility, what is important to recognize is that they all take place within the constraints, or guardrails, originally established by Mao. They are the bedrock of Chinese governancereflected in an oft-repeated phrase, The CCP leads everything.

Overall, we suggest that the United States and the West need to understand the Maoist playbook to be able to deal with China more effectively. As even Xi has said repeatedly, To understand China today, one must learn about the foundation of the CCP.

This in many ways may seem counterintuitive, as communism and capitalism are typically seen as diametrically opposed. However, as we show in this book, foundational economic policies and strategies in China can be traced back to Maoist principles. We aim to clarify the long-standing confusion about China and its contemporary economic model by tracing the deep communist roots of its enterprises and of the Chinese economy and state more generally. Our investigation of this understudied but critical topic has the potential to fundamentally change our understanding of private business in China, as well as how such a distinctive form of capitalism evolves, and even our understanding of recent shifts in governmental policy. This angle allows us to develop new insights for business practice, policy, and academic research, and provide a unique set of recommendations both for those who want to do business or invest in China and for policymakers. In the past, the United States paid a huge price for its inadequate knowledge and an automatic fear of communism, as exemplified by its involvement in the Korean and the Vietnam Wars. By approaching Chinas ideological system in a holistic way and from both the top down and bottom up, we provide a much clearer view of how it affects its economy and those who interact with it.

Next page