The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

He was, at the time, merely one of the American militarys up-and-coming officers, a young general who had distinguished himself more for his talents in Washington than through commands in the field. Still, when General Colin L. Powell rose to deliver a speech at the Army War College in Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, on May 16, 1989, he carried with him an unusual authority, conveyed by his having recently taken part in civilian events of surpassing importance.

Officially, Powell was the commander of U.S. Forces Command, which is responsible for all the U.S. troops stationed inside the United States. The post was less prominent than those of American commanders responsible for, say, the Middle East or Asia. But this job was merely a temporary placeholder for a rising star. During the previous two years Powell had served as the national security advisor to President Ronald Reagan, after having risen through a series of ever-more-important administrative jobs at the Pentagon and in the White House. He had played a leading role in organizing three summit meetings between Reagan and the Soviet leader Mikhail S. Gorbachev. Now, it was assumed, he was in line to fill a more exalted military post, such as army chief of staff. He was one of the few U.S. military leaders, if not the only one, who swapped friendly personal notes with ex-presidents, sitting presidents, and their wives.

In that spring of 1989, the world was in flux, in a way that seemed to benefit the United States. During Reagans final six weeks in office, Gorbachev had given a far-reaching speech to the United Nations in which he announced that the Soviet Union would cut the size of its armed forces by half a million troops and that, in the process, it would withdraw six armored divisions from Eastern Europe. Gorbachev had said that the countries there could determine their own destinies; thus, the Soviet Union was forswearing the right to intervene at will in the affairs of its neighbors. With that speech, Gorbachev had gone beyond the mere rhetoric of change in Soviet foreign policy and had given substance to his words. It was now possible to imagine that after more than four decades, the Cold War might draw to a close.

Powells message at Carlisle that day was that it was time for America to begin thinking about what would come next. He rejected the idea that Gorbachevs new policies were reversible. Though the old Soviet bear may be dying, Powell told the audience, Hes still a very formidable bear, and that we must never forget. But as a public and political matter our bear is wearing a Smokey hat and carries a shovel to put out fires.

Powell then posed the question that American leaders were just beginning to confront: So what does this all mean for us? Remember the old saw What will all the preachers do when the devil is dead?

That same month, the new secretary of defense, Dick Cheney, prepared a speech with a decidedly different outlook. Cheney, who had been White House chief of staff under President Gerald R. Ford and then served ten years in the House of Representatives, had taken charge of the Pentagon only two months earlier. It was a late, hurried appointment, made after the Senate had rejected President George H. W. Bushs first nominee, John Tower. During his first weeks on the job, Cheney had concentrated on learning his way around. En route to his first White House meeting, he got lost in the Pentagon basement. But by May 1989, when the new defense secretary was to deliver a speech at a Washington think tank, he was ready to give a detailed exposition of his views.

Cheneys views were essentially the opposite of Powells. There was no need for far-reaching change, he argued in his speech. The Cold War was not over. However genuine the reforms taking place in the Soviet Union, this is not the time to engage in a wholesale reworking of American defense policy, he asserted. He then took a step further, asserting that America would have to play a powerful role in the world even if the Cold War ended. Starting with World War II, he said, the United States had come to take the responsibility for seeing to it that liberty and free government had a congenial home in the world. In other words, Our commitment to the exercise of global military power became not just a temporary expedient, but a permanent condition.

As it turned out, the two speeches had little impact. In fact, Cheneys was never delivered. The White House rejected it as too hawkish. National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft and his staff felt that it might interfere with the ongoing diplomacy with Moscow being pursued by Secretary of State James Baker. So, the speech lay in a file, unused.

Nor did Powells speech in Carlisle get a much better reception. It was criticized from the opposite direction, for being too dovish. Scowcrofts deputy, Robert M. Gates, who for years had served as the CIAs leading Soviet analyst, telephoned Powell to say that the general shouldnt have been speaking in such broad terms about the Soviet Union. Senior military figures objected, too. They said, What are you doing? The Soviet Union isnt dead. Its coming back, recalled Lawrence Wilkerson, Powells speechwriter at the time.

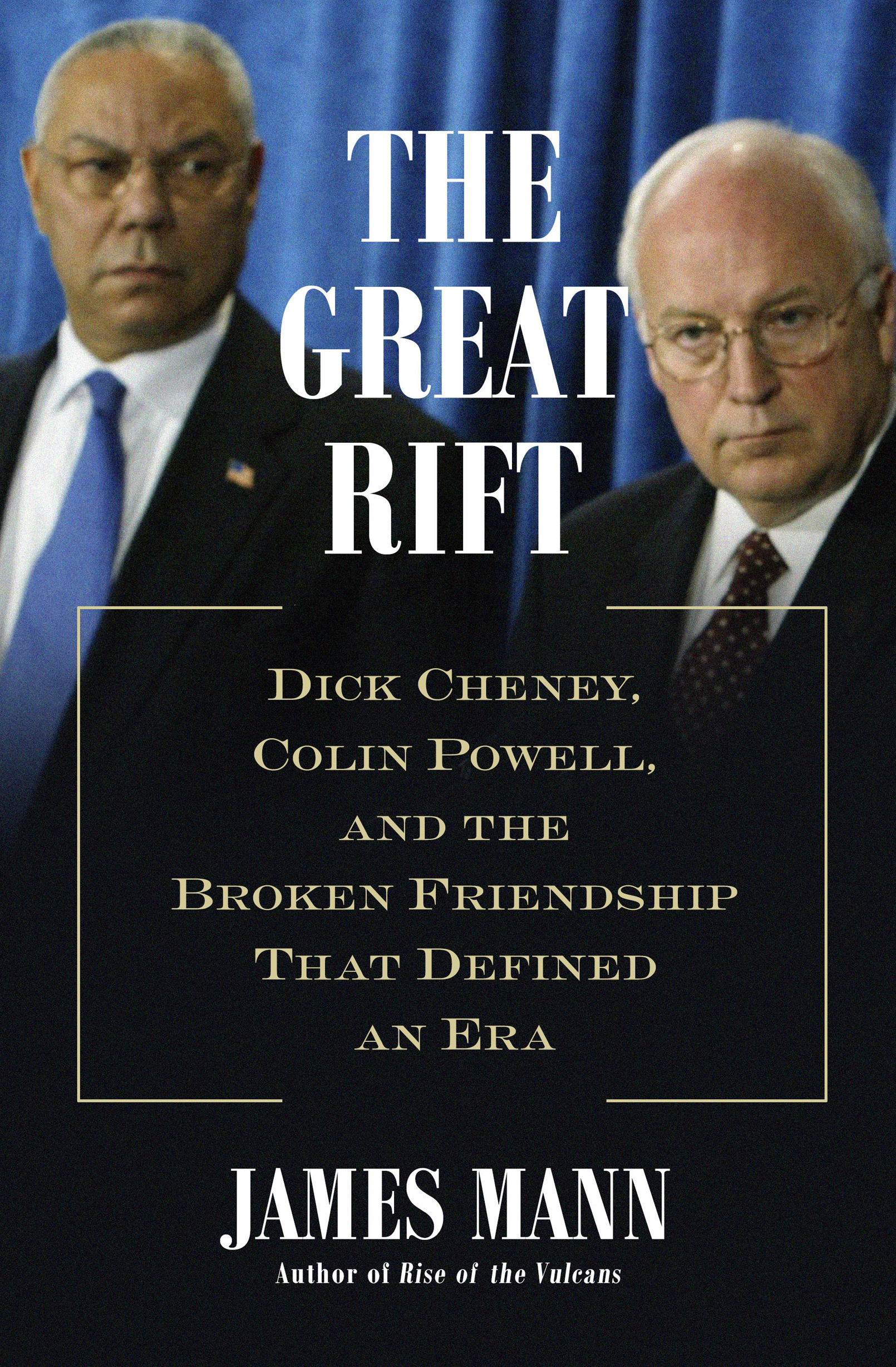

The Cheney and Powell speeches are a stark illustration of the divergent viewpoints of these two men, who would eventually emerge as leading antagonists at the highest levels of the U.S. government. Over the following two decades, at the end of the Cold War and in its immediate aftermath, the United States reached the pinnacle of its power in the world. At first, it was accorded almost universal deference as the sole remaining superpower, a nation that could and did wield its economic and military power at will so as to shape the world in the ways it thought best. Then it overestimated its power, launching costly military ventures that proved spectacularly unsuccessful. After two decades, America began to pull back, no longer confident of its success or its power, no longer enjoying the instinctive deference of other nations. Eventually, in the presidency of Donald Trump, it actively cast off its role as leader of the international community.

Colin Powell and Dick Cheney were among the leading public figures of the postCold War era. They were close partners in the triumphs of the George H. W. Bush administration, riding together in victory parades after the end of the Persian Gulf War. They returned to office again in the George W. Bush administration, this time as adversaries favoring opposing visions of Americas role in the world, as the United States embarked on its disastrous invasion of Iraq.

In their time, no other figures served so long at the top levels of American foreign policy as did Cheney and Powell. In the two decades between 1988 and 2008, Colin Powell served for nine years under four American presidents (Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush) as national security advisor, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and secretary of state. Over the same period, Dick Cheney served for twelve years, as secretary of defense under George H. W. Bush and as vice president under George W. Bush. Even the two-term presidents of the postCold War era (Clinton, the younger Bush, and Barack Obama) held high office for only eight years apiece. Cheney and Powell had greater longevity at the top than any of them.