Published in 2020 by New York Times Educational Publishing

in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Contains material from The New York Times and is reprinted by permission. Copyright 2020 The New York Times. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2020 The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved. Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

First Edition

The New York Times

Caroline Que: Editorial Director, Book Development

Phyllis Collazo: Photo Rights/Permissions Editor

Heidi Giovine: Administrative Manager

Rosen Publishing

Megan Kellerman: Managing Editor

Hanna Washburn: Editor

Greg Tucker: Creative Director

Brian Garvey: Art Director

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: New York Times Company.

Title: Plastic: can the damage be repaired? / edited by the New York Times editorial staff.

Description: New York: The New York Times Educational Publishing, 2020. | Series: In the headlines | Includes glossary and index. Identifiers: ISBN 9781642823660 (library bound) | ISBN 9781642823653 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781642823677 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: PlasticsEnvironmental aspects. | Plastic scrap Environmental aspects. | Refuse and refuse disposalEnvironmental aspects. | Recycling (Waste, etc.) Environmental aspects. Classification: LCC TD798.P537 2020 | DDC 628.44dc23

Manufactured in the United States of America

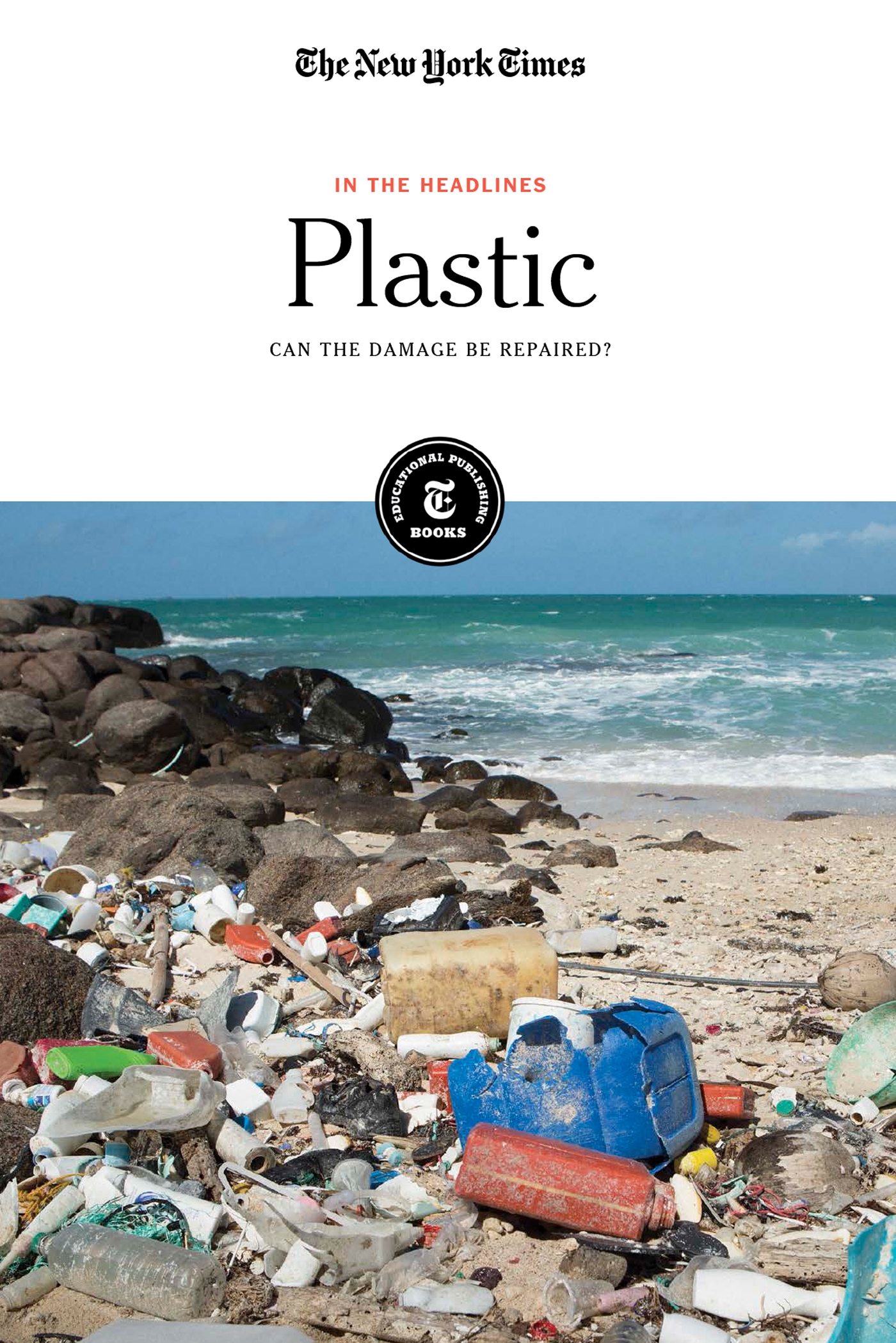

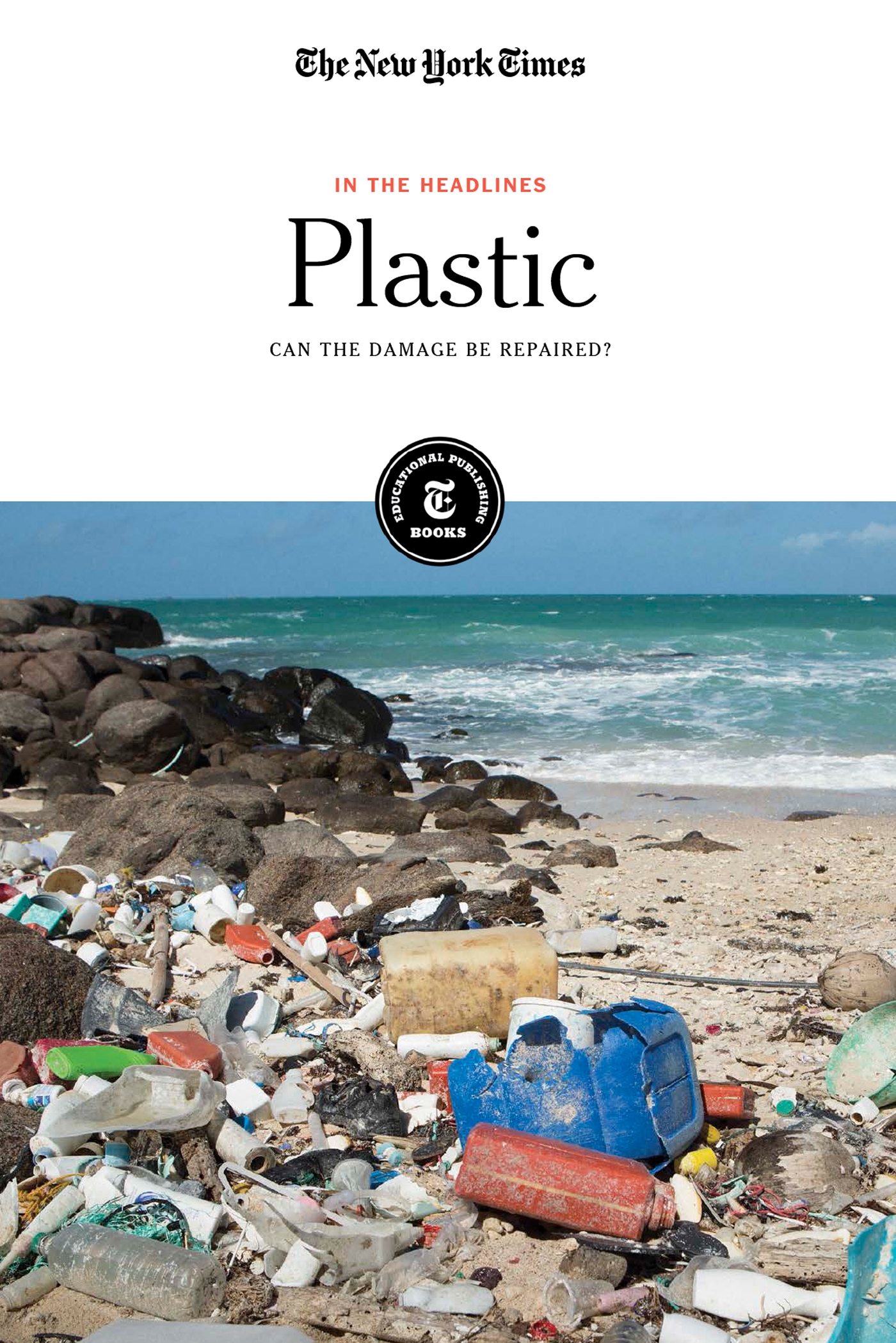

On the cover: An assortment of debris, largely plastic and believed to be mostly from Indonesia, that has washed up on the shores of Bremmer Island, off the coast of northern Australia, July 3, 2018; David Maurice Smith/The New York Times.

Contents

Introduction

SINCE THE 1940S, plastic has been an enormous part of our world, providing structure to the home and allowing advancements in science and technology. In the 21st century, the catastrophic effect of disposable plastics has become startlingly clear, wreaking havoc on our environment. The articles collected here recount the history of the plastics industry and suggest what the future may hold, including attempts to make plastic more biodegradable, the introduction of alternative materials and innovations in recycling.

In the early 20th century, advancements in chemical technology catalyzed innovations in the plastics industry, with mass production beginning in the middle of the century. Plastics manufacturing quickly became a significant component of the chemical industry, and some of the worlds largest chemical companies, such as Dow Chemical, were involved since the earliest days. It was not long before plastic was everywhere.

Due to their affordability, versatility and relatively easy production, plastics are used in a variety of manufactured products of all different kinds, from household goods to computers and airplanes. Plastics provide architectural structure to buildings and have many uses in the field of medicine. The flexibility and malleability of plastic during manufacture means it can be configured in a variety of ways: It can be cast or extruded into many different shapes and forms, such as films, fibers, bottles and boxes. This incredibly versatile material quickly became the preference over traditional materials such as wood, stone, leather and glass.

Plastic frequently takes the form of disposable goods, such as shopping bags and food containers. Once these products have performed their function, however, the rate of decomposition is remarkably slow. Plastics are synthetic polymers derived from petrochemicals, so it is very difficult for organic matter to penetrate and catalyze the process of breaking down plastic into smaller components. Since the earliest days of plastic production, environmentalists have questioned the sustainability of plastic, and voiced the potential risks of reliance on this synthetic material. Widespread excitement over this incredibly adaptable product initially quelled those who voiced concern over our growing dependence on plastic.

CHANG W. LEE/THE NEW YORK TIMES

An inmate picks up litter, including plastic bottles, at a dump site in Hickman County, Tenn., May 14, 2019.

The rapid ascent of the plastic industry in the 20th century, and relatively sudden ubiquity of plastic products, led to widespread environmental concerns regarding their slow decomposition rate. As the 20th century came to a close, decades worth of disposable plastics began to clog landfills and fill the oceans. The 21st century has seen a full-on environmental crisis. Whales and sea turtles wash up on beaches, killed by the floating plastic debris they have swallowed. Even microplastics pieces of plastic that are less than 0.2 inches long pose threats to marine life and are difficult to collect from ocean waters. One study in 2017 found microplastics to be present in tap water samples from around the world. Another study in 2018 found evidence of microplastics in the digestive systems of people from eight different countries. Microplastics are also part of something known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch an area in the Pacific Ocean that has been collecting waste and becoming, as journalist Livia Albeck-Ripka writes, a swirling oceanic graveyard where everyday objects get deposited by the currents.

This tragedy has been met by efforts to reduce plastic consumption, particularly of single-use plastics, and new solutions for reusing and recycling plastic material. The following stories examine the rise of plastics and the cultural and political forces driving the industry as well as provide tips for cutting down on plastic usage. They also highlight the environmental movement that arose in response and pose the question: Is a plastic-free future possible?

CHAPTER 1

Fantastic Plastic

After World War II, advancements in chemical technology allowed for innovations in plastics manufacturing. Plastic became cheap and easy to produce, and it proved to be a useful and versatile material. Though excitement over this innovation initially dominated, the 1970s saw increased concern over the slow decomposition rate of plastic, and the alarming amount of pollution it created. As the environmental movement gained traction, however, it could not halt the rapid production of this now ubiquitous material.

Huge Role Played by Plastics in War

BY THE NEW YORK TIMES | JAN. 3, 1943

IN ITS ALL-OUT EFFORT to respond to the countrys military needs last year, the plastics industry boosted the production of resins from about 450,000,000 pounds in 1941 to 600,000,000 pounds in 1942 and doubled in dollar value the output of molded and fabricated articles, according to a statement prepared exclusively for The New York Times by John M. Wetherby of the Society of the Plastics Industry. The dollar value of such products ran somewhere between $350,000,000 and $400,000,000.

Certainly the past year has seen more diverse plastics applications and developments than ever before and the industry faces the future with a confidence born of meeting the rigid tests of war, Mr. Wetherby said.

Prior to the outbreak of war in Europe, he pointed out, the plastics industry had concerned itself mainly with the production of such everyday things as electrical appliances, radios, parts for automobiles, decorative buttons and hundreds of similar items designed for eye appeal and general civilian well-being.

ANSWERED CALL SPEEDILY

Yet when the call came, Mr. Wetherby declared, the industry responded with a speed and efficiency that has been one to marvel at. Its technicians knew in a general way the characteristics of the various plastics available and they immediately set out to adapt them to the requirements of all-out war. The armed services and other government branches cooperated closely, outlining their needs and computing available supplies, with results that are daily becoming more apparent.

Next page