Published in 2017 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC 243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016

Copyright 2017 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC First Edition

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the prior permission of the copyright owner. Request for permission should be addressed to Permissions, Cavendish Square Publishing, 243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016. Tel (877) 980-4450;

fax (877) 980-4454.

Website: cavendishsq.com

This publication represents the opinions and views of the author based on his or her personal experience, knowledge, and research. The information in this book serves as a general guide only. The author and publisher have used their best efforts in preparing this book and disclaim liability rising directly or indirectly from the use and application of this book.

CPSIA Compliance Information: Batch #CS16CSQ All websites were available and accurate when this book was sent to press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Spence, Kelly, author.

Title: Martin Luther King Jr. and peaceful protest / Kelly Spence.

Description: New York : Cavendish Square Publishing, 2016. | Series: Primary sources of the civil rights movement | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version record and CIP data provided by publisher; resource not viewed.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016000362 (print) | LCCN 2015049738 (ebook) |

ISBN 9781502618658 (ebook) | ISBN 9781502618641 (library bound)

Subjects: LCSH: King, Martin Luther, Jr., 1929-1968--Juvenile literature. |

African Americans--Biography--Juvenile literature. | Civil rights workers--United States--Biography--Juvenile literature. | African Americans--Civil rights--History--20th century--Juvenile literature. |

Civil rights movements--United States--History--20th century--Juvenile literature. | Nonviolence--United States--History--20th century--Juvenile literature.

Classification: LCC E185.97.K5 (print) | LCC E185.97.K5 S67 2016 (ebook) |

DDC 323.092--dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016000362

Editorial Director: David McNamara Editor: Fletcher Doyle Copy Editor: Nathan Heidelberger Art Director: Jeffrey Talbot Designer: Amy Greenan Production Assistant: Karol Szymczuk Photo Research: J8 Media

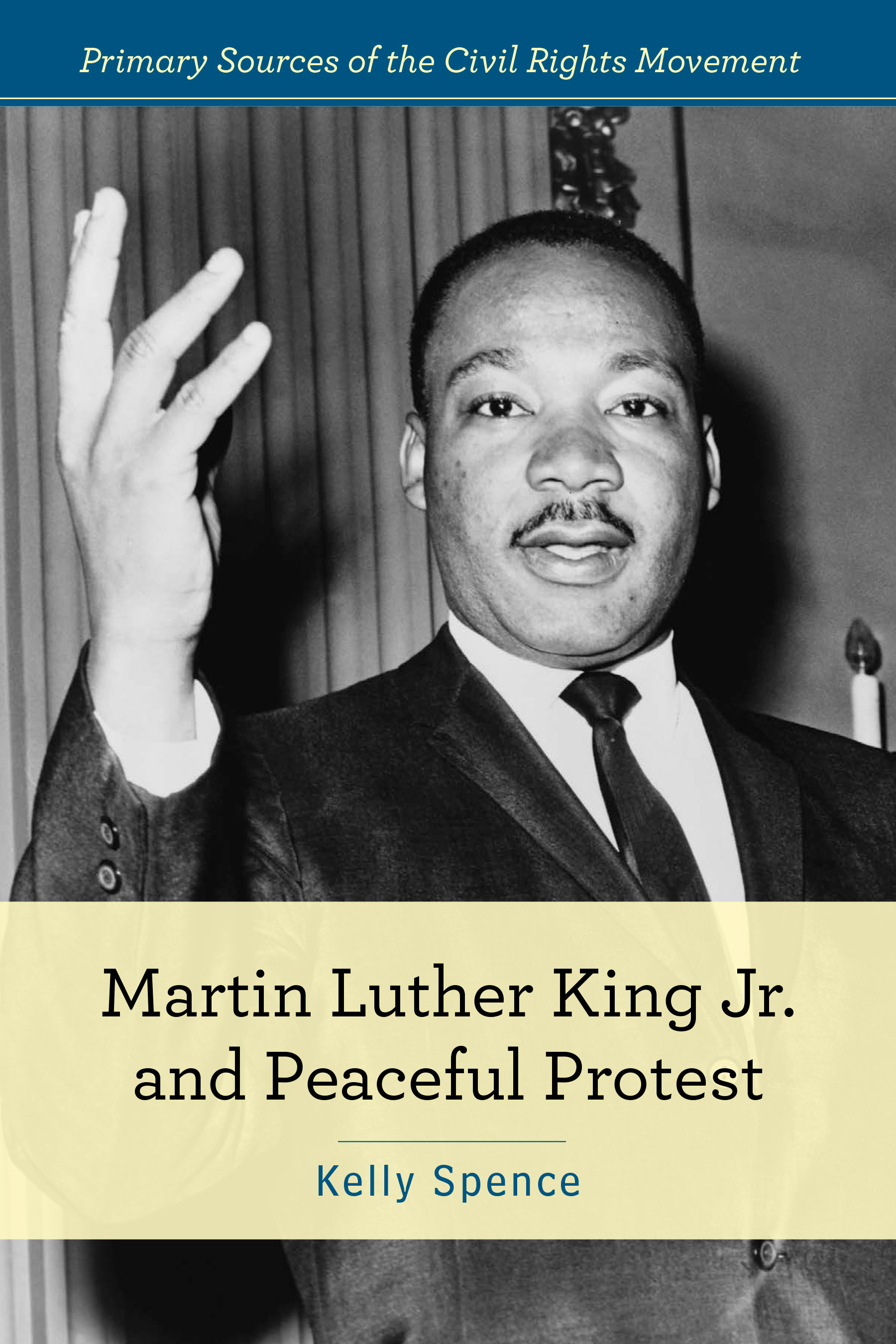

The photographs in this book are used by permission and through the courtesy of: Dick DeMarsico, World Telegram staff photographer/Library of Congress/File:Martin Luther King Jr NYWTS.jpg/Wikimedia Commons, cover; Engraving by W. Roberts/ File:EmancipationProclamation.jpg/Wikimedia Commons, 5; Jack Delano/PhotoQuest/Getty Images, 6; Yoshio Tomii/SuperStock/ Getty Images, 9; AP Photo/AJC, 10; Larry Burrows/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images, 12; Unknown/File:Salt March.jpg/ Wikimedia Commons, 13; Michael Evans/New York Times Co./Getty Images, 15; John Frost Newspapers/Alamy Stock Photo, 16; Universal History Archive/Getty Images, 19; Grey Villet/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images, 20; AP Photo, 21; Background Map: 1961 Freedom Rides (New York): Associated Press News Feature/Library of Congress Geography & Map Division, 25; Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images, 29; AFP/Getty Images, 30; AP Photo, 32; AP Photo/Larry Stoddard, 35; AFP/Getty Images, 36; Three Lions/Getty Images, 37; Hulton Archive/Getty Images, 39; Marion S. Trikosko, U.S. News & World Report Magazine/File:MLK and Malcolm X USNWR cropped.jpg/Wikimedia Commons, 40; AP Photo/Jack Thornell, 43; Joseph Louw/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images, 44; Declan Haun/Chicago History Museum/Getty Images, 46; AP Photo/Barry Thumma, 48; Universal History Archive/Getty Images, 49; Thomas S. England/Bloomberg via Getty Images, 51.

Printed in the United States of America

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

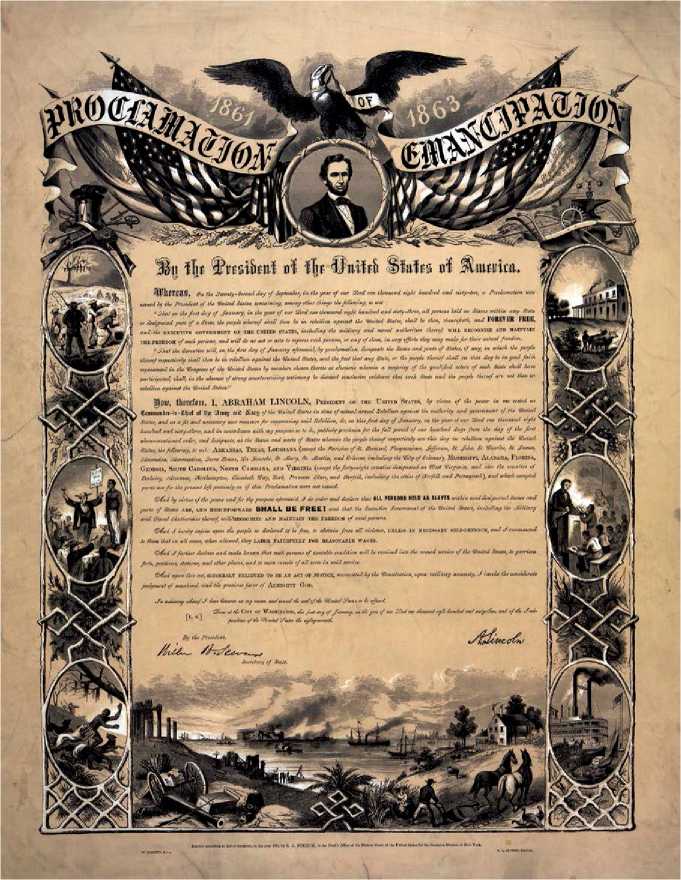

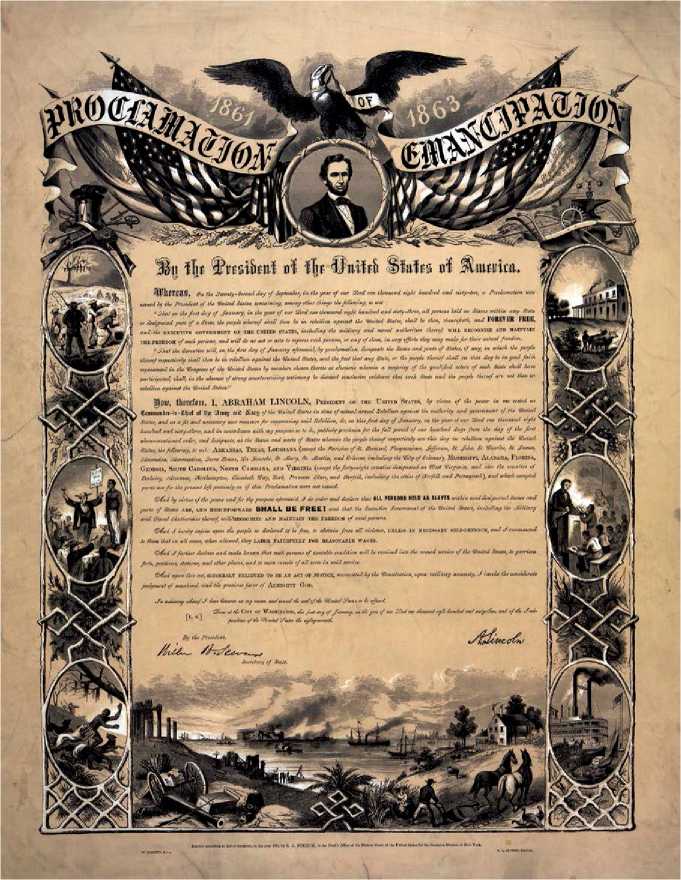

O n January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln freed millions of slaves living in the Confederate states by issuing the Emancipation Proclamation. This landmark action marked one of many steps that led to the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

Amendments to the Constitution of the United States following the end of the Civil War in 1865 expanded the scope of the proclamation. They extended basic rights to black people, whether they were freed slaves or had never been a slave. The Thirteenth Amendment prohibited slavery and involuntary servitude except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted. The Fourteenth Amendment asserted that no citizen would be denied equal protection under the laws, while the Fifteenth Amendment stated that the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. In the North, these rights were largely acceptedexcept for the right of women of all colors to vote, which would later be addressed by the Nineteenth Amendmentand blacks were free to exercise their rights without the overhanging threat of fear and violence.

This reproduction of the Emancipation Proclamation can be found at the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati.

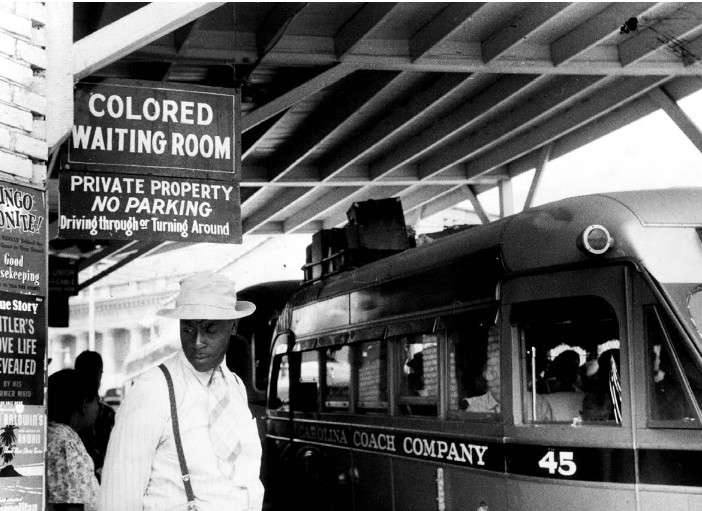

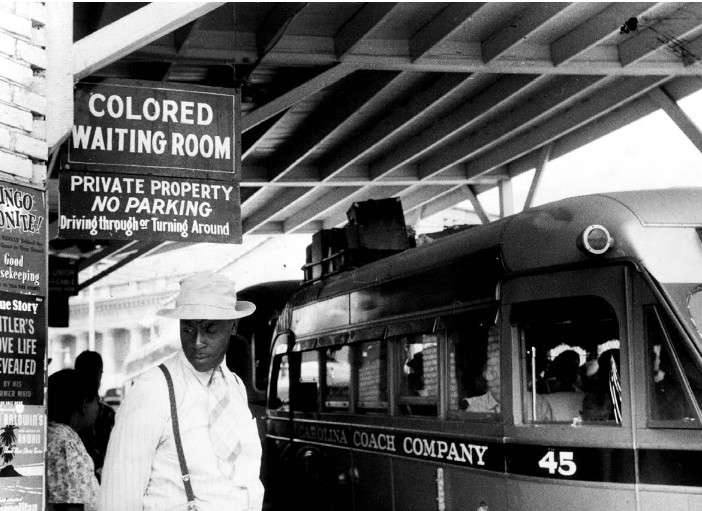

However, in the South during the 1950s, these liberties still were not extended. Civil War ideologies and racial discrimination lingered. Although blacks had been given freedom and rights decades earlier, for most people, segregation was a way of life, with Jim Crow laws in full effect. States and cities based these discriminatory laws on the idea of separate but equal. Equal, however, was not part of the daily experience for African Americans in the Southern states. In most public places, blacks and whites were kept strictly apart. On buses, blacks were required by law to sit in the back and to give up their seats to whites if the bus was full. Most public places, such as movie theaters, restaurants, and waiting rooms in bus stations, had separate entrances and rules for serving blacks and whites. Black children attended inferior schools that did not present the same education or opportunities afforded to white children. In the courts, acts of violence against blacks by whites went largely unpunished, with rulings by all-white juries overseen by white judges. This system of oppression was maintained through intimidation and by blocking blacks ability to vote and hold positions of power.

A sign designates where blacks are to wait for the bus in Durham, North Carolina, in 1940.

While people had been actively working toward overcoming segregation and creating equality for all races for decades, it was not until the mid-1950s that the civil rights movement began to fully take flight. At the head of this movement was Martin Luther King Jr., one of the most powerful leaders and influential orators of the era. His message of peaceful protest and nonviolence to bring about social change served as a cornerstone of the civil rights movement.