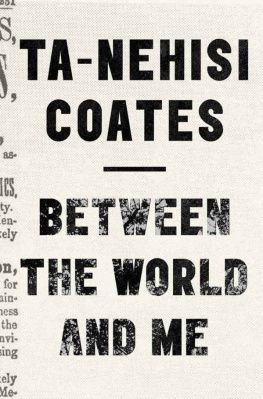

Summary and Analysis of

Between the World and Me

Based on the Book by Ta-Nehisi Coates

Contents

Context

In this book-length essay, Ta-Nehisi Coates addresses the history of racism in the United States, and its manifestation in current events and modern life, through the lens of his own experiences. The original work is presented as a letter to his son, Samori, to whom he wishes to impart certain lessons about being a person of color in America.

According to Benjamin Wallace-Wells reportage in New York magazine, Coates had been reading The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin when he met with President Obama and others for a discussion of universal health care. Aware of criticism that Coates had of the president, specifically about his current policies that acknowledge class but not raceand perhaps sensing Coates frustrationPresident Obama said to him, Dont despair.

Reflecting on Baldwins views (in contrast to the optimism of the early Civil Rights activists) during a discussion with his editor, Christopher Jackson, Ta-Nehisi Coates was challenged to pick up the mantle that James Baldwin left behind.

By the time Between the World and Me was published in 2015, Coates was already widely recognized for his powerful journalism, having been a reporter, feature writer, and blogger, often covering issues of race in America. He published a memoir in 2008 called The Beautiful Struggle , in which he spoke of what it was like growing up in Baltimore, and reflected on his relationship with his influential father, Paul Coates.

Drawing on the authors experiences, tremendous scholarship, and analysis of history, Between the World and Me should be considered in the context of current events, including multiple occurrences of police brutality against people of color, ever-present physical threats to black bodies, and the Black Lives Matter movement borne out of the acquittal of George Zimmerman, who shot and killed 17-year-old Trayvon Martin.

Overview

Ta-Nehisi Coates thesis is that race and racism are social constructs invented to keep racial minorities oppressed in service to Americans who believe they are white (a paraphrase from a James Baldwin quote). These constructs were woven into our society from its founding, through slavery, and continue to have dire consequences for people of color. America was built on the pillaging of life, liberty, labor, and land. He asserts that the complacent majority relies on a belief system he calls the Dreamthe Dream being a fantasy of white American Exceptionalism predicated on entitlement and the disenfranchisement of people of color.

Coates narrates his coming-of-age story, a constant grappling with the question, How do I live free in this black body? He recalls his youth in West Baltimore where the streets and the schools provided mutually reinforcing lessons about rules and order. On the streets, young boys postured at manhood, starting fights and selling drugs. In the schools, teachers were more concerned with obedience than education. Coates describes feeling somewhat rudderless, shifting between these two channels, never quite belonging to either.

When he discovers Malcolm X, and shortly thereafter arrives at Washington D.C.s Howard University, he is ecstatic to find kindred spirits.

The excitement is short-lived. Expecting to find easy answers to his questions about black identity, and something more glorious than the self-flagellation of Black History Month, he is disappointed. His favorite authors contradict each other and his own thoughts contradict themselves. While seeking a way to revere his black heritage, he idealizes his ancestors and identity, which is in fact, missing the point: that race is a false construct is equally useless whether being deployed for dehumanization or for glorification. It is all part of the Dream.

Coates opts to leave Howard and begins working as a freelance journalist. Shortly thereafter, his son, Samori, is born; he becomes the living embodiment of Coates years of theorizing. You are a black boy, he tells his child, and you must be responsible for your body in a way that other boys cannot know. Coates tells Samori that he is named after Samori Tour, an African resistance fighter who led armies against French colonizers in the late 19th century. The name is representative of the struggle black bodies still endure. Coates reminds his son that the Dream (and the country that supports it) was built on the backs of slaves.

After the birth of Samori, the most defining event in Coates life was the shooting of his friend Prince Jones by a black police officer. The policeman, who was known as corrupt, had shot Jones outside of his fiances house, reporting that Jones had threatened to run him over with his car. It was later revealed that the officer had pulled a gun on Jones and failed to identify himself as a cop.

The officer was not charged or punished in any way. Coates eloquently mourns his friend and all that was taken from the world as a result of his pointless death: the wasted potential shattered on the concrete; a young daughter deprived of her father. He relates this incident to his fears for his son: this could happen to anyone at any time. You are all we have, he writes, and you come to us endangered.

From here, Coates makes the claim that racist police and their violent actions are the consequences of the problem, not the problem itself. Society has organized itself to protect the Dream of white citizens, and the police are merely instruments to that end. Their actions are tacitly condonedexplicitly so when they are, for example, caught on camera ending a persons life and exonerated of all wrongdoing. The officer, Coates says, carries with him the power of the American state and the weight of an American legacy.

Soon after Princes death, Coates and his wife move to New York City. He observes with wariness the complete comfort of white Manhattanites in their surroundings. This is exemplified by an experience at a theater on the Upper West Side. Exiting the movie and coming down an escalator, a white woman pushes young Samori out of her way. When Coates snaps at her for touching his child, a white male bystander speaks up to defend her. There is a brief altercation and the man threatens to call the police. I could have you arrested, the man had said. Coates understands this warning to mean, I could take your body.

Here the author points out an incongruity in contemporary racial politicsthat widespread, systemic racism exists despite the fact that the vast majority of Americans claim they are not racist. He draws a parallel between a famous comedian declaring Im not a racist shortly after being filmed shouting the N-word, and the mass lynchings performed before the Civil Rights era: The perpetrators were bold enough to commit these acts, but not bold enough to admit to them.

This leads into thoughts on the Civil War. Coates is an avid visitor of battlefield sites and he describes his reception there wryly, as if I were a nosy accountant conducting an audit. He tells Samori, In America, it is traditional to destroy the black body, and recounts the savage violence of slavery explicitlythe rapes, beatings, maiming, and murdersstating that this is the legacy we all carry, either as descendants of the perpetrators or descendants of the victims. For the former, there is the Dream, for the latter, the struggle.

Coates recalls taking Samori to visit the mother of Jordan Davis, a Florida teenager shot and killed by a white man after refusing to turn down the music in his car. She is a righteous, stoic woman, harnessing her grief into activism. She tells Samori, You exist. You matter. You have value. The legacy destroys, but it can also build. The black community coalesces around a shared experience and common heritage, language and mannerisms, food and music, literature and philosophy, though it be forged in the shadow of the murdered, the raped, the disembodied.

Next page