Robert Guest - The Shackled Continent: Power, Corruption, and African Lives

Here you can read online Robert Guest - The Shackled Continent: Power, Corruption, and African Lives full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2010, publisher: Smithsonian, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Shackled Continent: Power, Corruption, and African Lives

- Author:

- Publisher:Smithsonian

- Genre:

- Year:2010

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Shackled Continent: Power, Corruption, and African Lives: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Shackled Continent: Power, Corruption, and African Lives" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Robert Guest: author's other books

Who wrote The Shackled Continent: Power, Corruption, and African Lives? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

The Shackled Continent: Power, Corruption, and African Lives — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Shackled Continent: Power, Corruption, and African Lives" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

2004 By Robert Guest

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in, or introduced into a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Published in 2004 in the United States of America

By Smithsonian Books

in association with Macmillan,

an imprint of Pan Macmillan Ltd

Pan Macmillan, 20 New Wharf Road, London N1 9RR

Basingstoke and Oxford

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Guest, Robert.

The shackled continent: power, corruption, and African lives /

Robert Guest. p. cm.

eISBN: 978-1-58834-311-6

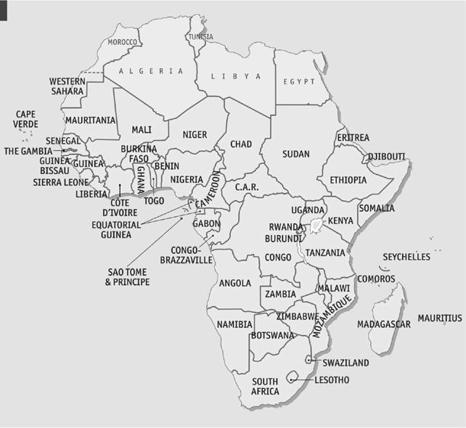

1. Political corruptionAfrica. 2. AfricaPolitics and government1960 3. AfricaSocial conditions1960

4. PovertyAfrica. I. Title.

JQ1875.A55C6378 2004

960.32dc 2004052131

v3.1

To Emma, for holding the babies while I slipped off to write

Acknowledgments

Barbara Smith, my editor at the Economist , has been a delight and an inspiration to work for. Stuart Evers, my editor at Macmillan, has shown a lighter touch in handling the manuscript than that Ivorian rebel I mentioned. Thanks to my agent, Andrew Lownie, for selling the book, and to James Astill, Tony Hawkins, Steve King, Philip Marsden, Anthea Jeffrey, and Broo Doherty for their helpful comments.

Among the many who have shared with me their insights and experiences, I am particularly grateful to Shantha Bloemen, Paul Collier, Ahmed Diraige, Nima El-Bagir, Comfort Ero, Franois Grignon, Heidi Holland, Dick Howe, Victor Mallet, Mesfin Wolde Mariam, Deligent Marowa, Strive Masiyiwa, Andy Meldrum, Fred Mmembe, John Robertson, Themba Sono, Thomas Sowell, Brian Williams, Nashon Zimba, and Faides Zulu. Of course, none of these excellent people should be blamed for any of my mistakes.

Finally, a word of thanks to the Cameroonian policeman I met at the thirty-first road block between Douala and Bertoua for unwittingly providing me with the best quote in the book.

London, August 2003

Contents

PREFACE

It was not much of a road block: a heap of branches and a broken fridge with a cows skull on top, painted the orange, white, and green of the flag of Cte dIvoire. But the rebels manning it had guns and rocket-propelled grenades, so we stopped.

There were about fifty of them, and they were determined to look tough. Some strutted around shirtless, with sashes of bullets wrapped around their chests. Others wore T-shirts with deaths heads on them. Most sported reflective sunglasses, and all except the most senior officer waved their weapons around carelessly. Several were drunk. It was 10:30 on a hot Ivorian morning, but the top was off the plastic jerry can of koutoukou , a throat-scalding local palm spirit, and young rebels were gulping it from battered tin cups.

They told us to get out of the car. I was traveling with Kate Davenport, another British journalist, and Hamadou Yoda, our Ivorian driver and guide. None of us wanted trouble, so we got out, stood in the road, and tried politely to explain our business while they searched our bags.

In my bag, one of them found the corrected first draft of this book, which I was hoping to read on spare evenings during this trip to report on Cte dIvoires civil war. It was a thick block of paper, held together with a rubber band. The rebel picked it up, waved it in my face, and demanded to know what it was. Its a book, I said. Whats it about? he asked.

Its about the abuse of power in Africa. It describes how men with guns, like you, have impoverished an entire continent, I wanted to reply, but of course I said nothing of the sort, though it would have been true.

In five years of reporting on Africa, Ive grown accustomed to seeing power abused. Some of the less media-savvy politicians are quite open about it.

I once had a conversation with the governor of a remote part of Namibia, where a minor uprising had just been put down with energetic brutality. Several hundred people had been tortured and then released without charge, presumably because they were innocent. Asked whether he was sorry that innocent people had been tortured, the governor told me his only regret was that he had not been able to take part in the beatings himself. I couldnt think of any more questions after that.

Africa about the prostitute in the lift illustrates a serious point.

On re-reading the text, it occurs to me that Ive left out a lot of the good things about Africa. The kindness of its people, their passion for life, the extraordinary hospitality of the poorest of the poor, the joy of Congolese rumba music, the sunset over the Okavango delta; the list goes on. But this is a book about why Africa is poor, so it has to grapple with war, pestilence, and presidents who think their office is a license, literally, to print money.

Africa has endured its share of evil leaders. The more colorful tyrants, such as Idi Amin and Mobutu Sese Seko, are well known. What is less well known is that, with so few effective checks on arbitrary power in Africa, its well-meaning leaders have often done great harm, too. Julius Nyerere, the revered former Tanzanian president, sincerely hoped to make his people better off by forcing millions of them into giant collectives, but instead he almost destroyed his nations capacity to feed itself.

The rebels at that Ivorian road block probably also thought they were fighting for a noble cause. To be fair, the government they hoped to overthrow was indeed an unpleasant one. But their revolution did not topple it. Rather, it split the country in two and exposed wide swathes of it to rape and pillage.

Not that we were badly treated. They only held us for an hour. We were given seats in the shade, near an old tape deck belting out dance tunes, and our guard kept offering us swigs of koutoukou . At one point, we watched him respectfully help a couple of old ladies up an earthy bank they had to climb in order to be questioned. All in all, this was a relatively disciplined group of rebels, which was a relief. But it would have been better if there had been no war, no road blocks, and no need to ask men with guns for permission to go about ones daily business.

By Africa, I mean sub-Saharan Africa. This book does not deal with the Arab countries of North Africa.

INTRODUCTION: WHY IS AFRICA SO POOR?

The helicopter swooped low over the floodwaters of southern Mozambique. The South African airmen sitting in the rear, legs dangling out of an open doorway, strained their eyes for a glimpse of survivors. I sat behind them, taking notes.

Poking out from the leaves of a tree that, despite the deluge, had somehow stayed upright, the pilot saw a scarlet shawl on a stick, waving to attract our attention. He took the helicopter down, and as we drew closer, the blast from its rotorblades flattened the canopy to reveal twenty-two Mozambicans clinging to the branches to avoid the churning waters below.

To rescue these people required hovering dangerously close to the tree, but the pilot did not hesitate. An airman rappeled down and strapped a little girl into his spare harness. The two were then winched back up. The airman quickly but gently handed the girl to his mate and rappeled down again. And again, and again, and again, until all twenty-two of the people in that tree were safely on board the helicopter.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Shackled Continent: Power, Corruption, and African Lives»

Look at similar books to The Shackled Continent: Power, Corruption, and African Lives. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Shackled Continent: Power, Corruption, and African Lives and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.