The names and identifying characteristics of some individuals in this book have been changed to protect the privacy of those involved.

PREFACE

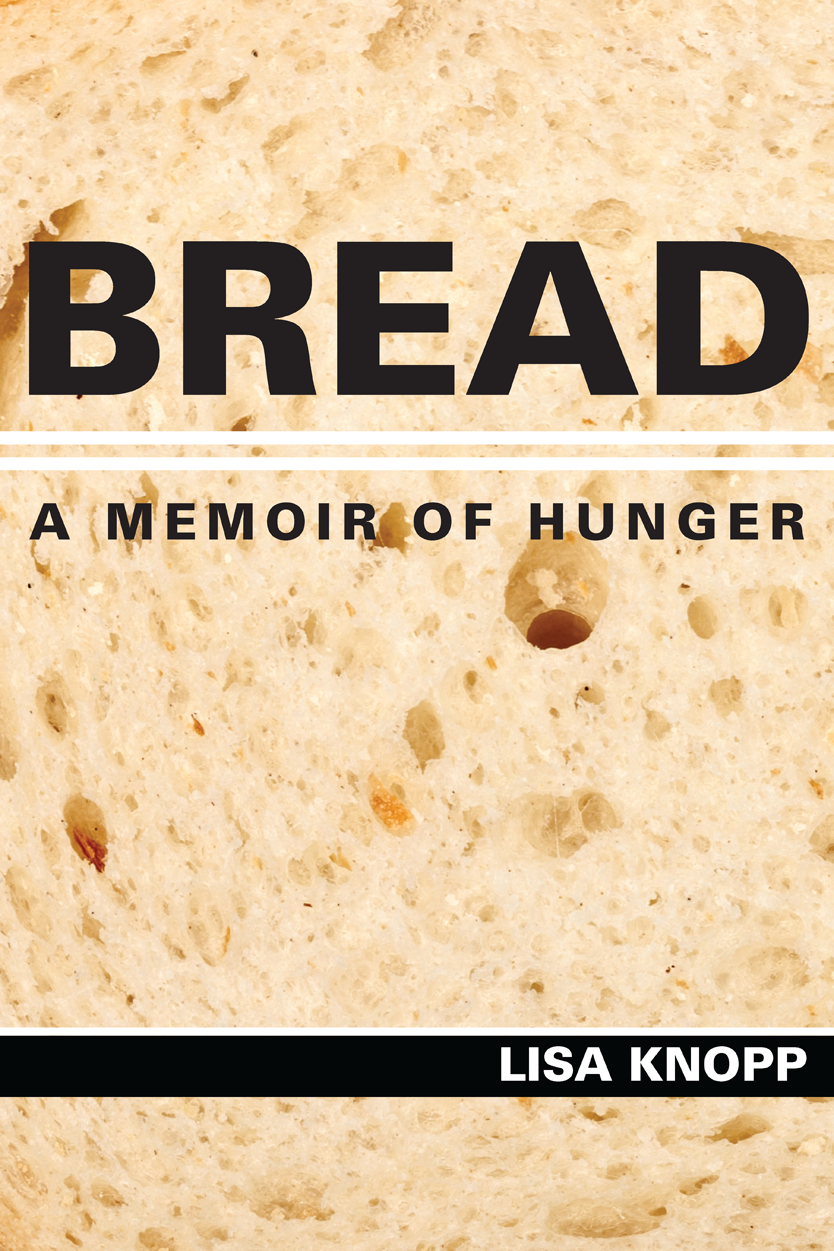

A few years ago, I found it very easy and very gratifying to tightly restrict what, when, and how much I ate. It was with a sense of triumph and delight that I watched myself becoming smaller and taking up less space. A whisper, a shadow, or a flicker is what I wanted to be. When I finally realized that the disordered eating that had left me sick and small when I was fifteen and again when I was twenty-five had returned when I was deep into middle age, I was full of urgent questions. Why did I respond to that which threatened or overwhelmed me by restricting my food intake? How can one heal from a condition that is the result of a tangle of genetic, biological, psychological, economic, and cultural forces? Are eating disorders and disordered eating in older women caused by the same factors as in younger women? Or are they caused, in part, by the sorrows and frustrations of aging in a culture that sees midlife and beyond as a time of inexorable decline marked by increasing deterioration, powerlessness, dependency, and irrelevance and so marginalizes older people? In my search for answers to these questions, I read studies by experts on eating disorders and revisited those dark periods in my life when reducing myself to skin and bones seemed like the best antidote to whatever was ailing me.

This book is the account of my efforts to understand the causes and nature of this perplexing and recurring problem in my life. In the introduction, I define terms, chiefly noting the difference between an eating disorder, which is a psychological illness and has a clinical diagnosis, and disordered eating, which is an abnormal or maladapted relationship with food, weight, body image, and self. I suspect that most women and too), I delve into the story of the unexpected return of my malady in my mid-fifties, when I responded to a cluster of separations and losses that left me feeling sad, empty, and hopeless by restricting my food intake, and the ways I eventually discovered to feed my deepest hungers.

I have many hopes for this book. I hope to convince readers that eating disorders and disordered eating are about more than just food and weight. I hope that the story of my malady and my search for understanding will inform and inspire those who also suffer from a conflicted relationship with food, weight, and self-image. Because eating disorders and disordered eating among older women are more common than most people realize, I hope to raise awareness about this hidden, little-studied, little-discussed phenomenon. I hope that those who eat normally and arent preoccupied with the number on the bathroom scale will find something in my story and reflections that speaks to them, too, since this is not only a food memoir and an illness narrative but a spiritual autobiography, concerned as it is with various appetites, hungers, desires, nourishments, and fulfillments.

Most books about eating disorders and disordered eating are written by medical doctors or psychologists, or by those who have been diagnosed with anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, or binge-eating disorder and treated by specialists in residential programs. I am none of these. I am a writer and this book is a work of creative nonfiction, a first-person account of one womans illness and what she learned about herself and her culture because of it. For those who are restricting, binging, or binging and purging or for those who are concerned about someone who is, no part of this book or my story is to be taken as a substitute for consultation with a medical or mental health professional.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I gratefully acknowledge those institutions and individuals that generously supported me in various ways during the writing of this memoir: Rock & Sling: A Journal of Witness, which published My Daily Bread in issue 11 (Spring 2016); the Kimmel Nelson Harding Center for the Arts in Nebraska City, Nebraska, for awarding me a three-week residency in January 2015; the Nebraska Arts Council for awarding me a $2,500 Distinguished Artist Award (creative nonfiction) through the 2015 Individual Artist Fellowship Awards in Literature program; the University of NebraskaOmaha for awarding me a sabbatical for the spring semester of 2015; and David Rosenbaum, Clair Willcox, Mary S. Conley, Sara Davis, Stephanie L. Williams, Deanna Davis, Drew Griffith, and all the others at the University of Missouri Press for their contributions.

I am more grateful than I can ever say to my editor, Gloria Thomas, my daughter, Meredith Ezinma Ramsay, and my mother, Patricia Knopp, who helped me to understand myself, my malady, and how to present my story.

MY MALADY

AN INTRODUCTION

When I tell people that I have written a memoir about my conflicted relationship with food, many of them tell me stories about being in the grip of something beyond their control that leads them to eat too much or too little, about feeling shamed or misunderstood or isolated because of their eating or not eating, about the familial or social tensions or the ill physical effects that have arisen because of their unhealthy relationship with food. Some of these storytellers meet the narrow diagnostic criteria for three of the eating disorders (anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder) listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the diagnostic bible of the American Psychiatric Association. But most do not. Most have disordered eating, which the authors of a 2009 study, Patterns and Prevalence of Disordered Eating and Weight Control Behaviors in Women Ages 2545, define as unhealthy or maladaptive eating behaviors, such as restricting, binging, purging, or use of other compensatory behaviors, without meeting criteria for an eating disorder. Maladaptive eating behaviors include imbalanced eating (for instance, avoiding an entire food group like carbohydrates or fats; eating only foods that one deems pure; crash dieting; and alternating between binging and fasting). Other compensatory behaviors include the use of laxatives, diuretics, stimulants, or excessive exercise to counteract the calories one has consumed. But the stories people tell me about their disordered eating are about more than stuffing or starving. The deeper stories are about the tellers feelings of unworthiness, emptiness, anxiety, self-consciousness, shame, or guilt. In short, they are stories about a hunger for wholeness and fullness.

Since most women, many men, and too many children in this time and place grapple with issues about eating, size, weight, and self-image, as well as the gnawing hungers that fuel these concerns, the story I tell and the stories I hear in response are common and representative. The authors of the 2009 study mentioned above found that of the women between the ages of twenty-five and forty-five that they surveyed, none of whom had a history of full-blown anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa, 31 percent reported using self-inflicted vomiting to control their weight, while 74.5 percent reported that their concerns about their shape and weight interfered with their happiness. Normative discontent is what psychologist Judith Rodin and her coauthors call the dissatisfaction that many people in economically developed countries feel about their body size, shape, and weight, even when their weight is normal. Apparently, maladaptive eating behaviors have also become normative. In

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.