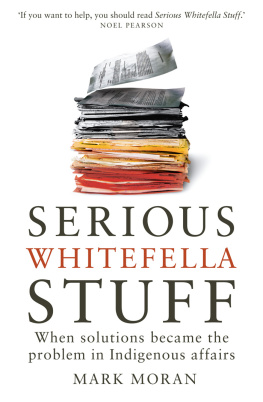

SERIOUS WHITEFELLA STUFF

SERIOUS

WHITEFELLA

STUFF

When solutions became the

problem in Indigenous affairs

MARK MORAN

MELBOURNE UNIVERSITY PRESS

An imprint of Melbourne University Publishing Limited

1115 Argyle Place South, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

mup-info@unimelb.edu.au

www.mup.com.au

First published 2016

Text Mark Moran, Alyson Wright, Paul Memmott, 2016

Individual photographs Mark Moran, Alyson Wright, Paul Memmott,

Vic Martin, 2016

Design and typography Melbourne University Publishing Limited, 2016

This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publishers.

Every attempt has been made to locate the copyright holders for material quoted in this book. Any person or organisation that may have been overlooked or misattributed may contact the publisher.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are respectfully advised that photographs of deceased people appear in this book and may cause distress.

A version of Chapter 2 entitled Mothers Know Best: Managing Grog in Kowanyama was originally published in Griffith Review, 40 (Women and Power) in 2013.

Text design and typesetting by Megan Ellis

Cover design by Design by Committee

Printed in Australia by McPhersons Printing Group

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Moran, Mark author.

Serious white fella stuff/Mark Moran.

9780522868296 (paperback)

9780522868302 (ebook)

Aboriginal AustraliansAustraliaAnecdotes.

Aboriginal AustraliansGovernment relationsAustralia.

Aboriginal AustraliansSocial conditions21st century.

Aboriginal AustraliansSocial life and customs21st century.

305.89915

Contents

About the Authors

Professor Mark Moran leads the Development Effectiveness group at the Institute for Social Science Research, The University of Queensland. His career spans academia, not-for-profit organisations, government and consultancy work. Mark has a unique background of technical and social science research with a degree in civil engineering and a PhD in human geography and planning. He has worked in Indigenous communities in Australia, USA and Canada, and in developing communities in Lesotho, China, East Timor, Papua New Guinea and Bolivia. He was awarded a Winston Churchill Fellowship in 1997 and The University of Queensland Deans Commendation for Outstanding Research Higher Degree Thesis in 2006. His writing has appeared in The Australian and Griffith Review.

Alyson Wright has a background in geography and epidemiology, and has studied at the Australian National University and Curtin University. Alyson has worked in a number of research and community development roles over the past fifteen years, in Papua New Guinea and in remote Indigenous communities in Australia. In 2004, Alyson moved to Alice Springs to work for the Centre for Appropriate Technology. She was engaged in a number of different research roles under the banner of the Desert Knowledge Cooperative Research Centre. She currently works at the Central Land Council as their policy researcher. She actively maintains close relationships with a number of communities across the Northern Territory.

Professor Paul Memmott is the director of the Aboriginal Environments Research Centre (AERC), and is based in The University of Queensland School of Architecture and Institute for Social Science Research. He has practised as both an architect and social anthropologist, diverging into allied areas such as settlement planning, social planning, strategic and management planning, social issue analysis, social organisation and land tenure. He is the author of nine books and 220 other publications on Indigenous cultural topics. He is the author of Gunyah, Goondie & Wurley: The Aboriginal Architecture of Australia (2007), which won several national book prizes including the Stanner Prize of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies.

Foreword

In Indigenous affairs there is a good deal of agreement about where we want to get toreduced government dependence, Indigenous people able to walk with confidence in two worlds as active participants in the prosperous economic and social life of the nation, and as members of living, vibrant Indigenous cultures. While there may be much agreement about this desired destination, there is far less agreement about how we are to get there.

Our understanding of the mechanics of change in Indigenous affairs is nascent at best. And at our peril, it is too often left entirely unexamined. Policy and politics in Indigenous affairs attract a great deal of attention. Practice, despite its critical importance, does not.

Serious Whitefella Stuff provides a rare examination of practice in Australian Indigenous affairsthe complex reality of what happens on the ground when policy and politics intersect with particular people and places. The book is a testament to those working at the frontline in Australias Indigenous communities to bring about hard-won change. I have been personally involved in many of the stories, sometimes directly, other times at arms length. The authors attention to detail and their unflinching critique, including at times of their own roles, makes for fascinating reading. It is often said that relationships are everything in Indigenous affairs. Serious Whitefella Stuff does better than those before it to bring these relationships to light. Here, detailed portraits show the central importance of relationships to building change, over time, and step by stepwhether to respond to the scourge of alcohol, revitalise cultural practices, establish outstations, or realise a desire for home ownership.

Achieving change within communities is only half the job. The other half is getting large numbers of stakeholders in a complex system to change as well. Imposed change towards the mainstream, without commensurate commitment by those in government to learn, adapt and themselves change, is just another form of assimilation. It is when we have an Indigenous view of what development entails (in different places), accompanied by an Indigenous view of how change of beneficiaries and stakeholders will occur towards achieving those development aspirations, then we have what can be called Indigenous Development. Rights to land and social justice remain critically important, but we also have to advocate for our Right to Development; this is our true right.

The corpus of learning about the practice of Indigenous Development in Australia is far too small. There is little systematic effort to ensure that we are building this corpus, and applying the lessons learnt through practice to our overarching policy approaches, or to provide input into the political debate.

This book invites comparison with international developmentfew of the usual expectations that apply to those working in international development, apply to those involved in Indigenous Development in Australia. To work at the frontline in an Australian Indigenous community, one is not expected to have dedicated professional training (the point is made that no such university training exists!), as is the case in the field of international development. Nor is it expected that to work in Indigenous affairs one must be committed to working over the long term with a place and its people through intermittent but lengthy postings, or that an effort must be made to learn the Indigenous language or languages of that place. Imagine an international development worker professing to have a credible opinion about what will work to promote social and economic development in Indonesia, without ever having lived there, or worked on the ground with Indonesian people to help bring about change? Yet too often this is exactly the situation we face in Indigenous affairs. The buffeting winds of policy and politics emanating from Canberra, Brisbane and Darwin are heedless to the importance of building on voices of experience and the lessons to be learnt from practice on the frontline.