The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

100th Missile Defense Brigade, Colorado Springs, Colorado

SUSAN FROBE-RECELLA: original crew member

MARCUS KENT: original crew member

KEVIN KICK: brigade commander (September 2016December 2018)

TIM LAWSON: brigade commander (July 2014September 2016)

DAVE MEAKINS: original crew director

RICHARD MICHALSKI: original crew member, crew director

MATT POLLOCK: crew director

GREG SIMPSON: original crew director

BILL SPRIGGS: original crew member

MICHAEL STRAWBRIDGE: crew director

PATRICIA YOUNG: crew member

MICHAEL YOWELL: brigade commander (April 2006May 2009)

49th Missile Defense Battalion, Fort Greely, Alaska

RON BAILEY: crew member

GREG BOWEN: battalion commander (July 2003May 2006), brigade commander (May 2009July 2012)

JARROD CUTHBERTSON: MP, battalion and brigade crew member

BETHANY HENDREN: MP, crew member

ED HILDRETH: battalion commander (May 2006July 2008), brigade commander (July 2012July 2014)

MARK KIRALY: MP, battalion and brigade crew director

RAY MONTOYA: crew director, MP company commander

JEANETTE PADGETT: MP, crew member

JOHN ROBINSON: MP platoon sergeant, battalion and brigade crew member

MARK SCOTT: MP, battalion security

Missile Defense Agency, Arlington, Virginia (moved to Fort Belvoir, Virginia, in 2011)

RON KADISH (US AIR FORCE): MDA director from June 14, 1999

HENRY TREY OBERING III (US AIR FORCE): MDA director from July 2, 2004

PATRICK OREILLY (US ARMY): MDA director from November 21, 2008

JAMES SYRING (US NAVY): MDA director from November 19, 2012

ANY INCOMING US PRESIDENT gets briefed on the threats and options of nuclear warfare. The choices arent good and the dynamic is particularly tricky with North Korea, with its bellicose history, long-range missiles, and nuclear weapons. Somebody has to tell the president about the limited options, and this unenviable job typically falls to the vice-chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. That four-star officer must travel to the White House and first explain the choice between preemption and interdiction.

Preemption would be when the intelligence community reports a possible intercontinental ballistic missile, or ICBM, being stacked on a North Korean launchpad. The president would need to decide upon a wait-and-see approach or a preemptive strike to destroy that missile. International law says a preemptive strike is an act of war, but it is more open to interpretation if that act might be justified. Legal arguments can be made either way and the context is important: Is it possibly a test launch? Could it be a satellite payload and not a warhead? Has Pyongyang been publicly threatening to turn New York City into a sea of fire? One group of government lawyers might argue that just stacking the boosters on the launchpad could be considered a hostile act, while another group of government lawyers might argue that its not a hostile act until the missile has been launched at the United States. The president must also be warned that preemptive strikes are not guaranteed to be successful. A missile could get through and hit the United States anyway.

Interdiction is a simpler, but equally unpalatable, concept: the Pentagon steps into the fight after a missile has already been launched at the United States. This could include the president ordering a retaliatory nuclear strike, but immediately after an enemy launch the authority for self-defense is already delegated to Northern Command, which could try to destroy the hostile warheads. Intercepting the warheads sounds like a great alternative, a respite in this otherwise horrific briefing about nuclear war. Unfortunately, at this point in the presidents briefing, the vice-chairman must explain how difficult ICBM intercepts are. About ninety seconds after North Korea launches, the Pentagon will know the trajectory thanks to infrared satellites overhead and radar on US Navy ships or at fixed sites in Japan. The interceptor system needs to see and track the missile at two points to plot where it is heading, and then at a crucial third point to get good enough data to triangulate an intercept. Those satellites, radar, communication networks, and computer systems all must work properly.

The missile needs about twenty-eight minutes to travel from North Korea to, say, Seattle. Within that, there will be about a seven-minute window from the time the inbound missile crosses over the interceptor systems third radar horizon, within sight of the Cobra Dane radar station on the small island of Shemya in Alaskas Aleutian chain. The first two minutes and last two minutes of that window are statistically bad for an intercept attempt, so US Army missile crews plot their launches to hit the warhead somewhere in a three-minute time frame in the middle. The sweet spot. Four or five interceptors might be launched to collide with that one incoming warhead in the sweet spot, but the interceptors intricate components all must work properly too.

The last part of the vice-chairmans briefing is especially unhappy, because then the president is told that there might not be sensors or radars available that can see whether the interceptors actually destroyed the warhead. If the entirety of the system works, you might not know youve killed the warhead until its full twenty-eight-minute flight time has passedthe only measure of success would be that, when the countdown hits zero, Seattle isnt smoldering under a mushroom cloud.

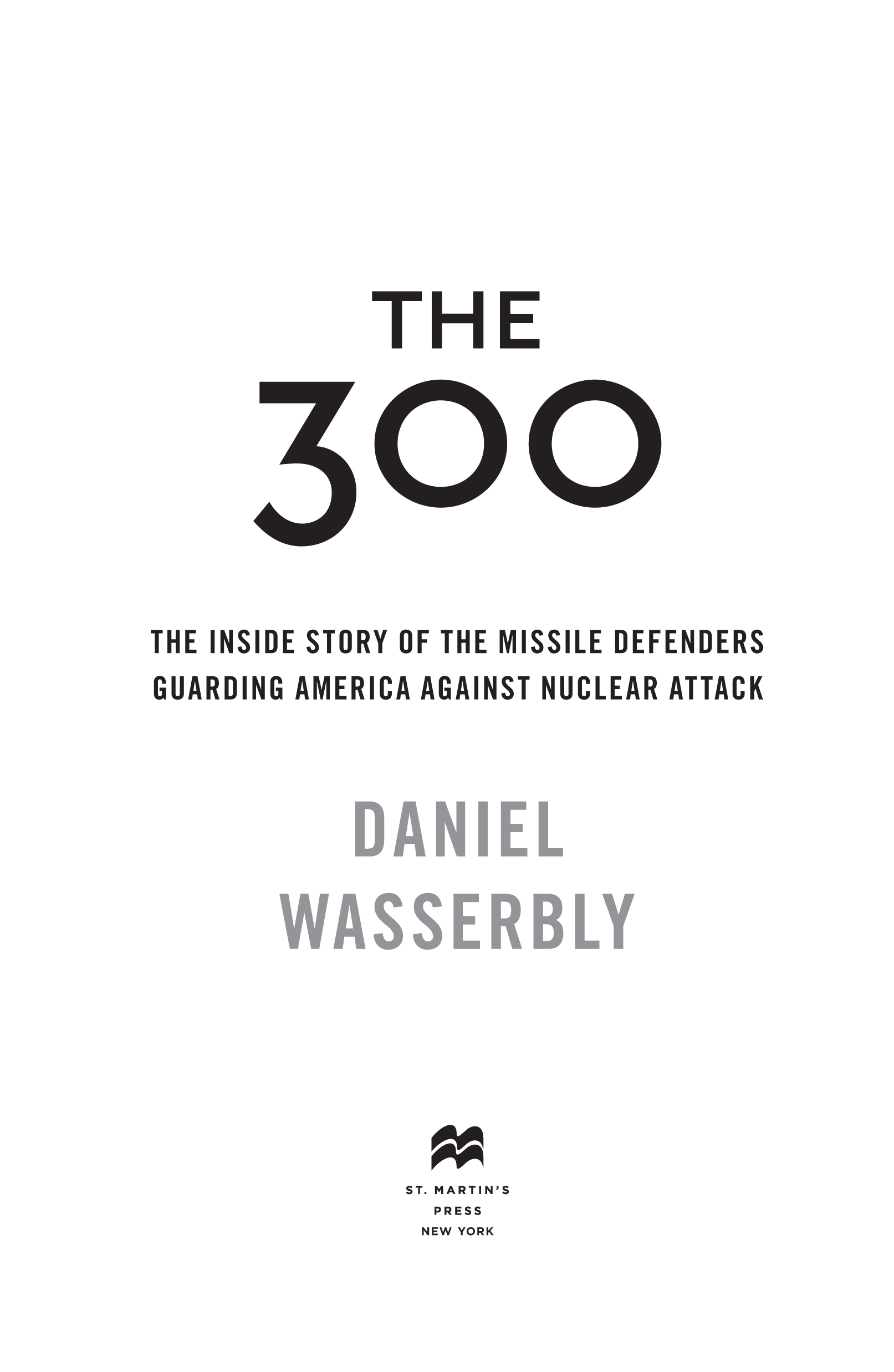

The incredibly difficult mission of homeland missile defense is assigned to the US Armys 100th Missile Defense Brigade and 49th Missile Defense Battalion. Just three hundred soldiers. The small, unconventional unit calls itself the 300, homage to the Spartans who fought at the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BC. Except instead of using swords and shields as did the Spartans to defend the Greeks, the modern-day 300 use phased-array radars and advanced aerospace engineering (yes, it is rocket science) to defend three hundred million Americans. They are asked to defend the United States from nuclear missile attacks, to sit and monitor and learn and train and relearn and retrain in perpetuity, waiting for the grim day when their skills might be demanded. This is their story.

THE QUICK ALERT SOUNDED, a flashing white light and a shrill beep, beep, beep. At Schriever Air Force Base in Colorado Springs, across town from Cheyenne Mountain, the alert warns the 100th Missile Defense Brigade that an intercontinental ballistic missile has been launched. Five army operators from Charlie crew man their consoles.

They sit in a control station known as a node, a small room with five work consoles in a horseshoe. Each console has a double-decker phone bank with two receivers and an assortment of black, blue, and red direct-dial buttons. At the front of the room, five big TVs hang from a low drop-ceiling. On the center TV, a digital globe of Earth rotates to display a red circle where the missile launch was detected. The circle is on Panghyon Aircraft Factory in North Korea. On the screen, a red threat fan begins to bloom out from the circle at the launch location. The fan depicts the missiles expected path and, for now, it only shows the missile is traveling east. If the fan becomes an ellipse, showing the missiles path from North Korea toward the United States, Charlie crew may be ordered to destroy the missile.