Published in 2016 by Britannica Educational Publishing (a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.) in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2016 by Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2016 The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

To see additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, go to rosenpublishing.com.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

J.E. Luebering: Director, Core Reference Group

Anthony L. Green: Editor, Comptons by Britannica

Rosen Publishing

Ann Hosein: Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Brian Garvey: Designer

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Rona Tuccillo: Photo Researcher

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Political science / edited by Ann Hosein.

pages cm (The Britannica guide to the social sciences)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-6227-5547-9 (eBook)

1. Political scienceJuvenile literature. I. Hosein, Ann.

JA70.P65 2016

320dc23

2015017695

Photo Credits: Cover, p. 1 marigold_88/iStock/Thinkstock; pp. viii-ix Aaron P. Bernstein/Getty Images; p. 2 DEA/A.Dagli Orti/De Agostini/Getty Images; p. 7 H. Roger-Viollet; p. 14 Hulton Archive/Getty Images; p. 17 Lee Lockwood/Black Star; p. 21 Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call Group/Getty Images; pp. 32, 87 Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc.; p. 34 Bachrach/Archive Photos/Getty Images; p. 38 Angelo Palma/A3/contrasto/Redux; p. 47 Edward Linsmier/Getty Images; p. 52 iStockphoto.com/Andrew Cribb; p. 59 W. Eugene Smith/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images; p. 63 Robert King/Hulton Archive/Getty Images; p. 66 Jana Birchum/Getty Images; p. 69 Eva Hambach/AFP/Getty Images; p. 77 Lanmas/Alamy; p. 82 Danita Delimont/Gallo Images/Getty Images; pp. 98-99 traveler1116/E+/Getty Images; p. 103 Fazimoon Samad/Alamy; p. 106 NARA; p. 114 WPA Pool/Getty Images; p. 120 Willis D. Vaughn/National Geographic Image Collection/Getty Images; p. 123 Photos.com/Jupiterimages; p. 128 Charles O. Cecil/DanitaDelimont.com Danita Delimont Photography/Newscom; p. 131 Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London; p. 134 Courtesy of the Muse d'Art et d'Histoire, Geneva; photograph, Jean Arlaud; p. 142 Courtesy of the trustees of the British Museum; photograph, J.R. Freeman & Co. Ltd.; p. 149 Courtesy of University of Rochester

CONTENTS

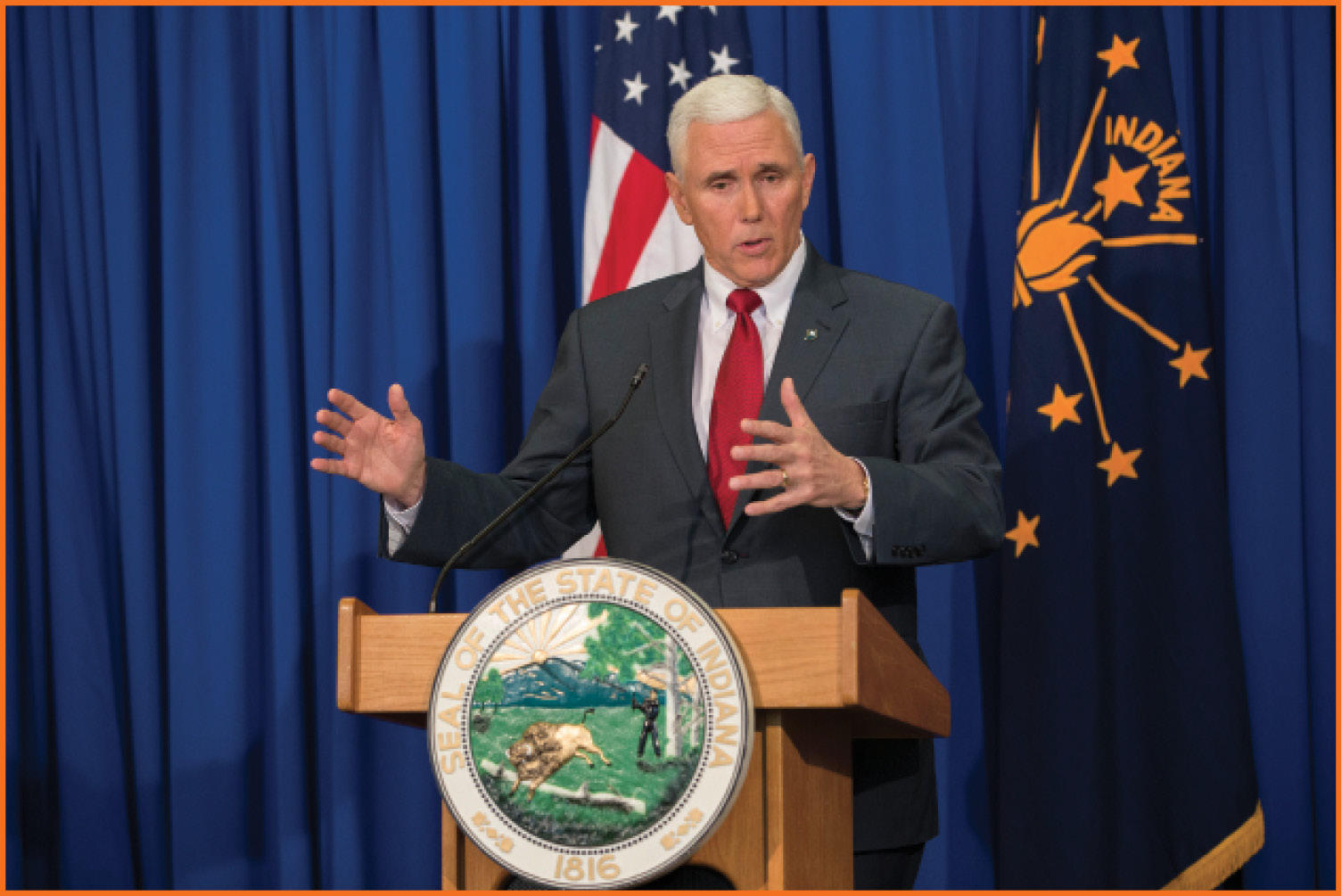

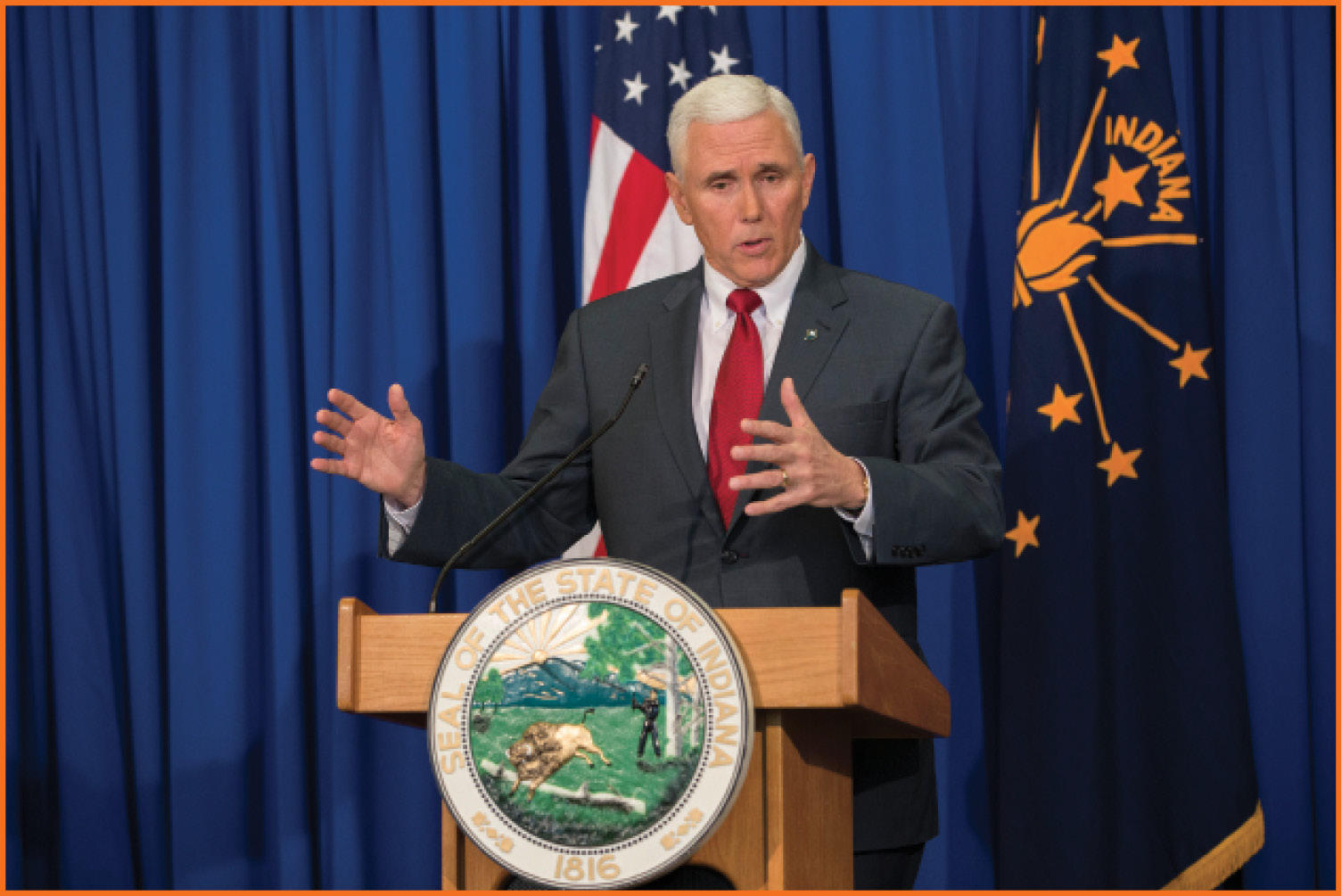

I n 2015, Indiana Governor Mike Pence caught the attention of the country with a religious freedom law that stirred up a firestorm in the press and social media. Newspapers, news stations, and media pundits from around the world weighed in on the subject and the new laws legality and implications. What had been a promising political career quickly became radioactive with a future that was murky at best.

Political scientists are racing to determine and quantify the circumstances that have led to a national furor over the law. How did a states law become the focal point for a larger issue? What role did the media play in Governor Pences freefall? Finding the answers to these questions can define the success or failure of a politicians career, determine popular public opinion, and ultimately shape the laws that govern a nation.

Indiana governor Mike Pence speaks about the Religious Freedom Restoration Act in March 2015.

Political science is the systematic study of governance by the application of empirical and generally scientific methods of analysis. As traditionally defined and studied, political science examines the state and its organs and institutions. The contemporary discipline, however, is considerably broader than this, encompassing studies of all the societal, cultural, and psychological factors that mutually influence the operation of government and the body politic.

Although political science borrows heavily from the other social sciences, it is distinguished from them by its focus on powerdefined as the ability of one political actor to get another actor to do what he or she wantsat the international, national, and local levels. Political science is generally used in the singular, but in French and Spanish the plural (sciences politiques and ciencias polticas, respectively) is used, perhaps a reflection of the disciplines eclectic nature. Although political science overlaps considerably with political philosophy, the two fields are distinct. Political philosophy is concerned primarily with political ideas and values, such as rights, justice, freedom, and political obligation (whether people should or should not obey political authority); it is normative in its approach (i.e., it is concerned with what ought to be rather than with what is) and rationalistic in its method. In contrast, political science studies institutions and behaviour, favours the descriptive over the normative, and develops theories or draws conclusions based on empirical observations, which are expressed in quantitative terms where possible.

So how does this play into what happened in Indiana? The controversial legislation, officially called the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (SEA 101), was meant to ensure religious liberty is fully protected under [Indiana] law, according to Pence. The heart of the law was found in the following clause: A [state] governmental entity may not substantially burden a persons [defined as an individual, business, religious institution or association] exercise of religion, even if the burden results from a rule of general applicability.

The criticism of the law, and main thrust of critics arguments, is that the law allows business owners to deny service to groups typically targeted with discrimination. Previous lawsuits in other parts of the country have seen the state side with the customer. Indianas reaction was to legally support businesses religious objections. Taken to the logical extreme, say critics, businesses can deny service to people of any religion, sexual orientation, or any other group they choose. Although discrimination could theoretically apply to any group, the debate focused on the gay and lesbian community who traditionally had been targeted by groups based on their moral or religious convictions.

A number of groups mobilized to protest the legislation. This includes other state governors such as Democratic Connecticut governor Dan Malloy who announced an executive order that barred state-funded travel to Indiana. We are sending a message, said Malloy over social media, that discrimination wont be tolerated. Seattles openly gay mayor Ed Murray followed suit with a similar executive order. Local businesses and organizations also expressed concern over the law. The NCAA is headquartered in Indianapolis, and the associations president Mark Emmert said, we intend to closely examine the implications of this bill and how it might affect future events as well as our workforce.

Businesses that exert a large influence beyond their respective industries joined in the debate as well. Apple CEO Tim Cook wrote in a Washington Post op-ed that Americas business community recognized a long time ago that discrimination, in all its forms, is bad for business. Business-rating site Angies List put a halt to its plan to expand into Indiana, and software company Salesforce canceled all Indiana-based events and travel responsibilities.