First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2007 by

Portobello Books Ltd.

Copyright Raj Patel 2007

Melville House Publishing

145 Plymouth Street

Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.mhpbooks.com

The permissions found at the end of this book constitute an extension of this copyright page.

eISBN: 978-1-61219-029-7

Cover Design by Carol Hayes

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

v3.1

For the everyday heroines and heroes.

Contents

Introduction

Our Big Fat Contradiction

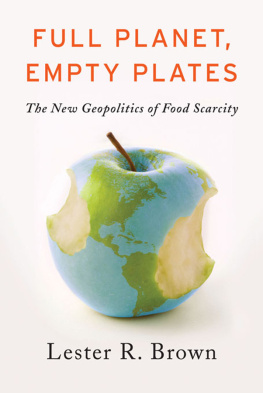

Today, when we produce more food than ever before, more than one in ten people on Earth are hungry. The hunger of 800 million happens at the same time as another historical first: that they are outnumbered by the one billion people on this planet who are overweight.

Global hunger and obesity are symptoms of the same problem and, whats more, the route to eradicating world hunger is also the way to prevent global epidemics of diabetes and heart disease, and to address a host of environmental and social ills. Overweight and hungry people are linked through the chains of production that bring food from fields to our plate. Guided by the profit motive, the corporations that sell our food shape and constrain how we eat, and how we think about food. The limitations are clearest at the fast food outlet, where the spectrum of choice runs from McMuffin to McNugget. But there are hidden and systemic constraints even when we feel were beyond the purview of Ronald McDonald.

Even when we want to buy something healthy, something to keep the doctor away, were trapped in the very same system that has created our Fast Food Nations. Try, for example, shopping for apples. At supermarkets in North America and Europe, the choice is restricted to half a dozen varieties: Fuji, Braeburn, Granny Smith, Golden Delicious and perhaps a couple of others. Why these? Because theyre pretty: we like the polished and unblemished skin. Because their taste is one thats largely unobjectionable to the majority. But also because they can stand transportation over long distances. Their skin wont tear or blemish if theyre knocked about in the miles from orchard to aisle. They take well to the waxing technologies and compounds that make this transportation possible and keep the apples pretty on the shelves. They are easy to harvest. They respond well to pesticides and industrial production. These are reasons why we wont find Calville Blanc, Black Oxford, Zabergau Reinette, Kandil Sinap or the ancient and venerable Rambo on the shelves. Our choices are not entirely our own because, even in a supermarket, the menu is crafted not by our choices, nor by the seasons, nor where we find ourselves, nor by the full range of apples available, nor by the full spectrum of available nutrition and tastes, but by the power of food corporations.

The concerns of food production companies have ramifications far beyond what appears on supermarket shelves. Their concerns are the rot at the core of the modern food system. To show the systemic ability of a few to impact the health of the many demands a global investigation, travelling from the green deserts of Brazil to the architecture of the modern city, and moving through history from the time of the first domesticated plants to the Battle of Seattle. Its an enquiry that uncovers the real reasons for famine in Asia and Africa, why there is a worldwide epidemic of farmer suicides, why we dont know whats in our food any more, why black people in the United States are more likely to be overweight than white, why there are cowboys in South Central Los Angeles, and how the worlds largest social movement is discovering ways, large and small, for us to think about, and live differently with, food.

The alternative to eating the way we do today promises to solve hunger and diet-related disease, by offering a way of eating and growing food that is environmentally sustainable and socially just. Understanding the ills of the way food is grown and eaten also offers the key to greater freedom, and a way of reclaiming the joy of eating. The task is as urgent as the prize is great.

In every country, the contradictions of obesity, hunger, poverty and wealth are becoming more acute. India has, for example, destroyed millions of tons of grains, permitting food to rot in silos, while the quality of food eaten by Indias poorest is getting worse for the first time since Independence in 1947. In 1992, in the same towns and villages where malnutrition had begun to grip the poorest families, the Indian government admitted foreign soft drinks manufacturers and food multinationals to its previously protected economy. Within a decade, India has become home to the worlds largest concentration of diabetics: people often children whose bodies have fractured under the pressure of eating too much of the wrong kinds of food.

India isnt the only home to these contrasts. Theyre global, and theyre present even in the worlds richest country. In the United States in 2005, 35.1 million people didnt know where their next meal was coming from. At the same time there is more diet-related disease like diabetes, and more food, in the US than ever before.

Its easy to become inured to this contradiction; its daily version causes only mild discomfort, walking past the homeless and hungry signs on the way to supermarkets bursting with food. There are moral emollients to balm a troubled conscience: the poor are hungry because theyre lazy, or perhaps the wealthy are fat because they eat too richly. This vein of folk wisdom has a long pedigree. Every culture has had, in some form or other, an understanding of our bodies as public ledgers on which is written the catalogue of our private vices. The language of condemnation doesnt, however, help us understand why hunger, abundance and obesity are more compatible on our planet than theyve ever been.

Moral condemnation only works if the condemned could have done things differently, if they had choices. Yet the prevalence of hunger and obesity affect populations with far too much That geography matters so much rather overturns the idea that personal choice is the key to preventing obesity or, by the same token, preventing hunger. And it helps to renew the lament of Porfirio Diaz, one of Mexicos late-nineteenth-century presidents and autocrats: Pobre Mexico! Tan lejos de Dios; y tan cerca de los Estados Unidos (Poor Mexico: so far from God, so close to the United States).

A perversity of the way our food comes to us is that its now possible for people who cant afford enough to eat to be obese. Children growing up malnourished in the favelas of So Paulo, for instance, are at greater risk from obesity when they become adults. Their bodies, broken by childhood poverty, metabolize and store food poorly. As a result, theyre at greater risk of storing as fat the (poor-quality) food that they can access.

As consumers, were encouraged to think that an economic system based on individual choice will save us from the collective ills of hunger and obesity. Yet it is precisely freedom of choice that has incubated these ills. Those of us able to head to the supermarket can boggle at the possibility of choosing from fifty brands of sugared cereals, from half a dozen kinds of milk that all taste like chalk, from shelves of bread so sopped in chemicals that they will never go off, from aisles of products in which the principal ingredient is sugar. British children are, for instance, able to select from twenty-eight branded breakfast cereals the marketing of which is aimed directly at them. The sugar content of twenty-seven of these exceeds the governments recommendations. Nine of these childrens cereals are 40 per cent sugar. Its hardly surprising, then, that 8.5 per cent of six-year-olds and more than one in ten fifteen-year-olds in the UK are obese. And the levels are increasing. The breakfast cereal story is a sign of a wider systemic feature: theres every incentive for food producing corporations to sell food that has undergone processing which renders it more profitable, if less nutritious. Incidentally, this explains why there are so many more varieties of breakfast cereals on sale than varieties of apples.