I am grateful to the many people who have helped me while I was writing this book. Professor Jeremy Black has been characteristically generous and supportive, and I am very grateful to him for inviting me to contribute this volume to the series. Leo Hollis has combined the helpfulness and encouragement of an editor with the steady eye of a fellow early modern scholar. Graham and Amina Hughes, Mary Sweeney, Byron Young and Laura Cairns read and commented on this book to my great benefit. Each of them took considerable time and trouble to help improve it and I owe them a debt of gratitude. I alone am responsible for the errors and shortcomings it retains. I have included dates for some but not all of the individuals in this book; I have not done so for better-known figures, whose dates will be familiar, or for those who role is only incidental.

In 1839 the sixty-eight-year-old Reverend Sydney Smith marvelled at the changes he had seen during his lifetime. He thought of gas lighting, without which he had groped about the streets of London; of railways, which saved him from the 10,000 contusions he suffered in stage coaches; umbrellas and waterproof hats; braces, which enabled him to keep my small clothes in their proper place; banks to receive the savings of the poor; posts to whisk letters to the remotest corners of the empire for a penny. He wrote: I am ashamed that I was not more discontented, and utterly surprised that all these changes and inventions did not occur two centuries ago. Unimaginable products were available, such as whale oil for lamps, first extracted in 1748, and by Smiths day it had become a staple commodity, with a million gallons of oil exported to Europe from North America.

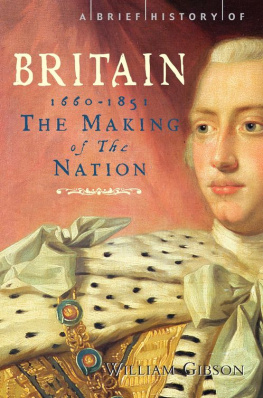

But Sydney Smith was only skimming the surface of the unprecedented changes that happened in Britain between 1660 and 1850. As a nation, Britain in this period underwent dramatic alterations. In 1660 Britain was still a geographical term for three separate kingdoms: England (united with Wales), Scotland and Ireland. During our period these kingdoms became a single United Kingdom. In 1660 Britains global possessions were modest in comparison with the Dutch and Spanish empires. Within two hundred years Britains empire was truly global and provided strategic interests in every corner of the world.

The monarchy changed radically. In 1660 kings were warriors who led their troops in battle; they chose their ministers and determined their policies. Charles II ruled as well as reigned. He appointed ministers at will, declared war and signed a treaty with France without his ministers knowledge. Charles even maintained the fictional claim to be king of France. Much of his reign was preoccupied by who would succeed him. The reigns of Charles brother and nieces were to be consumed by rumours of invasions, plots and revolts. By 1850 the sovereigns role was becoming largely ceremonial and in politics that of a constitutional monarch. Queen Victoria was obliged to choose her prime minister from the party with the majority in the House of Commons, and was expected to follow her prime ministers advice. In the Bedchamber Crisis of 183941, she was even forced to concede that the prime minister was responsible for appointing her household staff. Her uncle, William IV, had already conceded the primacy of the Commons over the Lords. He agreed that a prime minister with a majority in the Commons could insist on making enough peers to swamp opposing votes in the House of Lords.

The economy had also seen unimaginable changes. In 1660 Britains economy was that of a pre-industrial society; there was no large-scale manufacturing. The national debt and effective taxation were yet to be devised. By 1850 not only had Britain become the first industrial nation, but manufactured goods marked Birmingham, Sheffield or London could be found on every continent. In consequence, Britain had developed an industrial working class, the professional and middle classes, and the structures of finance, transport, urbanization and education to support the industrial economy.

Social conditions in Britain were transformed in this period. In 1660 Britain was profoundly hierarchical, with the king, aristocrats and landowners ruling society. It was a society framed by the divine sanction of the Church and a society in which most people saw themselves as subjects not citizens. Social relations were governed by faith, deference and duty. By 1850 people lived under a Bill of Rights that guaranteed the rule of law, and increasing numbers had the right to vote. The government recognized that it had the duty to intervene to legislate in many areas of society, something that was unthinkable in 1660. Merit, rather than kinship or patronage, was becoming more important, and people had increasing expectations that talent and education counted for more than family relationship or a patrons influence in appointments to many jobs.

Britain in this period would appear and sound strange to someone from the twenty-first century. In reading this book you will have to step into a past that is different from modern Britain in many ways. For example, the English that people spoke in 1700 would sound very odd to us today and it was also spelled erratically. Lord Peterborough pronounced his title Peterbrow and the Duke of Marlboroughs title was often pronounced Marlborrow and sometimes Marlbroo. Alexander Pope rhymed tea with obey. Milton had rhymed end with fiend and sea was often pronounced say. The way Americans today pronounce clerk, Derby, Berkeley and leisure are the way they were said in England in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The separation of the letter W from V was still underway in 1660, so some late seventeenth-century guides to London referred to VVestmynster.

The lack of standard pronunciation led to the publication of a number of pronouncing dictionaries during the eighteenth century, the most popular of which was written by Thomas Spence. Spence addressed his Grand Repository of the EnglishLanguage (1775) to the working people of the country. He told people that strut rhymed with foot and put. Some people pronounced lord as laard. Cucumber and asparagus were pronounced cowcumber and sparrow grass. In the mid-eighteenth century there were furious discussions between Lord Chesterfield and Sir William Yonge whether great should be pronounced to rhyme with state or seat. Words such as hostile and servile would have been pronounced with a short ill sound at the end. In fact, there were many differences in pronunciation, and eighteenth-century English would sound very peculiar, perhaps incomprehensible, to us. Even at the time, the differences were noted. Sheridans Course of Lectures on Elocution of 1762 noted that cockney and court end (West End) accents had created a linguistic divide in London.

Words are as fashion-prone as clothes, and many came and went in this period. We no longer use shrammed (meaning cold) or gradely (for thorough) or fettle (meaning make though it remains in the phrase fine fettle). Today we might use hew (to quarry or dig), which was first recorded in 1708 (although of Old English origin), or clout (which was brought to England by Irish navvies), and dunny for a lavatory was exported to Australia from eighteenth-century England. By the end of this period, Liverpool was beginning to receive the large influx of Irish immigrants who gave the citys dialect its distinctive Liverpudlian twang.

The years 16601851, stretching from the Restoration of Charles II to the middle of the Victorian period, lend themselves to two big interpretations: those of the optimist and of the pessimist. The optimistic Whig interpretation of this period would suggest that it was one of progress and advancement. Led by the development of the constitution from a divine right monarchy into a parliamentary monarchy, this optimistic account of the period would emphasize the development of the economy, the growth of towns, roads, canals and, in the nineteenth century, railways. It would also see the development of empire as a cause and reflection of material wealth and political liberty and would argue that this was the era of great scientific and cultural achievement, from Isaac Newton and Robert Boyle to Nicholas Hawksmoor and George Gilbert Scott, from Alexander Pope to the Bronts. It was also the time of the British Enlightenment.