A BRIEF HISTORY OF BRITAIN 10661485

NICHOLAS VINCENT

FOR HENRY MAYR-HARTING

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Some years ago, a colleague of mine remarked, The thing is, Nick, that neither you nor I are ever going to write a book that anyone will want to read. What follows is intended to test that statement. It is decidedly neither a textbook (of which there are many splendid examples) nor a piece of undiluted scholarship targeted at a few dozen scholars, none of whom, save the reviewers (and even then not all the reviewers), will ever read it. It must open with an apology. My title and my task were given to me already formed. To all Welsh, Scots, Manx, Irish or Channel Island readers, it is necessary to point out that this particular brief history of Britain focuses almost exclusively upon the history, indeed upon the Birth of the Nation, of England, with barely a glance towards other undeniably British concerns. To trace the history even of England from the beginnings to 1485, is itself a daunting task. To have done so in tandem with a narrative of other British histories, themselves drawn from very different source materials, would have resulted in a story as confused and as set about with reefs and shipwrecks as the rocky western coast of Britain itself. Excellent histories of Wales, Scotland and Ireland already exist, and readers are urged to explore them. As for the English history which follows, I have both the privilege and the pleasure to belong to a history department at Norwich, and more broadly to a community of scholars, whose friendship and mutual support have ensured that medieval studies flourish today as never before, and that our connection with other scholarly communities, particularly in France, are stronger now than they have been at any time since the nineteenth century. Those who responded to requests for information or who talked over various of the issues in this book, not always aware of the fact that their pockets were being picked, include Martin Aurell, John Baldwin, Julie Barrau, David Bates, Paul Binski, Paul Brand, Christopher Brooke, Bruce Campbell, Martha Carlin, David Carpenter, Stephen Church, Alan Cooper, David Crouch, Peter Davidson, Hugh Doherty, John Gillingham, Chris Given-Wilson, Christopher Harper-Bill, Sandy Heslop, Jim Holt, Nicholas Karn, Simon Keynes, Edmund King, Tom Licence, Rob Liddiard, Roger Lovatt, Scott Mandelbrote, Lucy Marten, Gesine Oppitz-Trotman, Michael Prestwich, Carole Rawcliffe, Miri Rubin, Richard Sharpe, Henry Summerson, Tim Tatton-Brown, Alan Thacker, Tom Williamson and Andy Wood. There are a lot more who might be named, not least the many dozens of scholars whose contributions to the new Oxford Dictionary of National Biography I have mined with such pleasure and such a sense of my own essential ignorance.

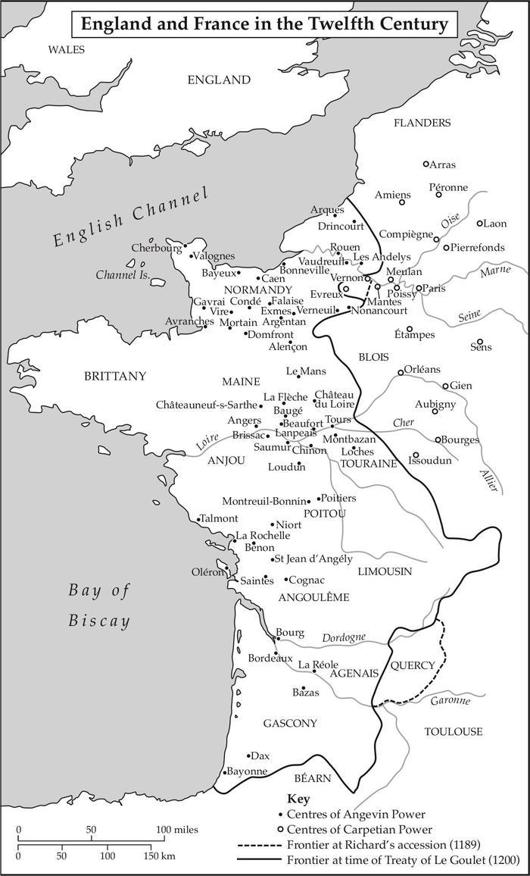

All accounts of history are the product of their own time. It is no coincidence that after 1970 or so, historians began to explore the impact of inflation upon the politics of England in the 1180s, or that the ethnic cleansing practised (or not practised ) by the Normans after 1066 first became a burning issue after 1990, with the former Yugoslavia almost daily in the newspapers. The present book was written in a time of economic crisis, following the great credit crunch of 2008, in the midst of warfare in Iraq and Afghanistan, and in the face of glib assertions from the usual quarters that if long-term educational , cultural and economic decline do not finish off the British, then environment and ecological factors almost certainly will. I began writing it in Caen, in November 2009, within sight both of the castle from which William the Conqueror planned his conquest of England and of the University, founded by Henry VI, one of the last acts of English patronage in Normandy. Warfare and education have always sat rather well together. Most of the final chapter was written at Fontevraud or Poitiers in May 2010, the last pages at Rouen, within sight of the place where Joan of Arc was tried and executed. What I know of the period after 1300, I owe to the teaching of Roger Highfield and in particular to John Maddicott, who turned me from an early into a high medievalist but who failed to eradicate what he already suspected might be a populist streak in my prose. The book as a whole is dedicated to Henry Mayr-Harting, prince amongst teachers and an inspiration to the generations of undergraduates whom he has tutored.

Nicholas Vincent

Norwich

Midsummer 2010

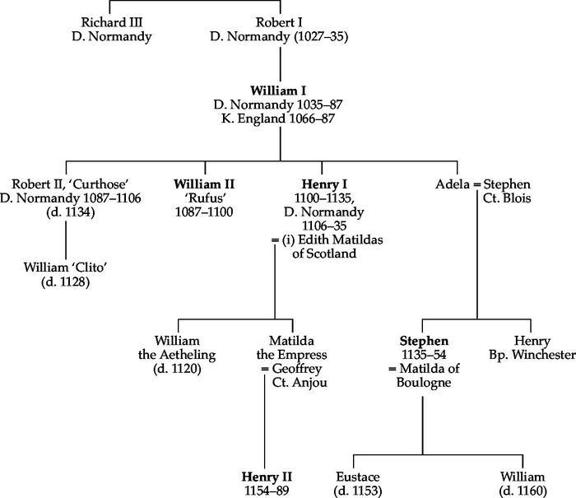

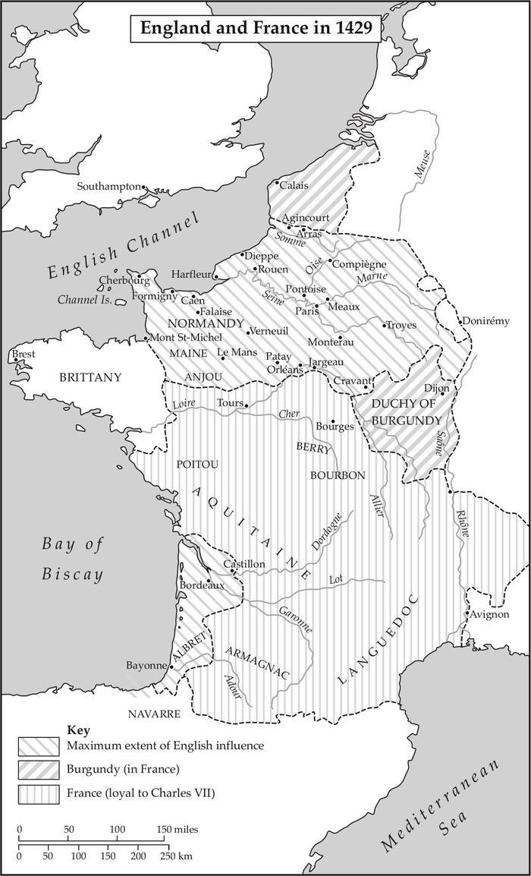

MAPS AND FIGURES

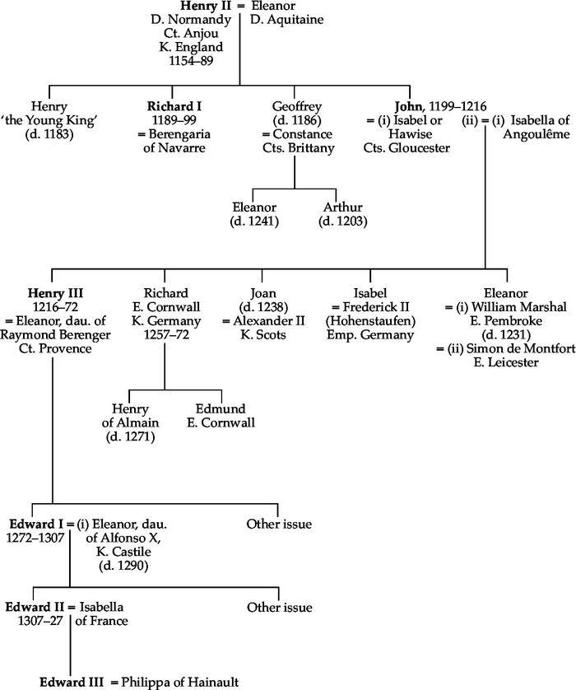

1. Genealogy of the Kings of England 10661154

2. Genealogy of the Kings of England 11541327

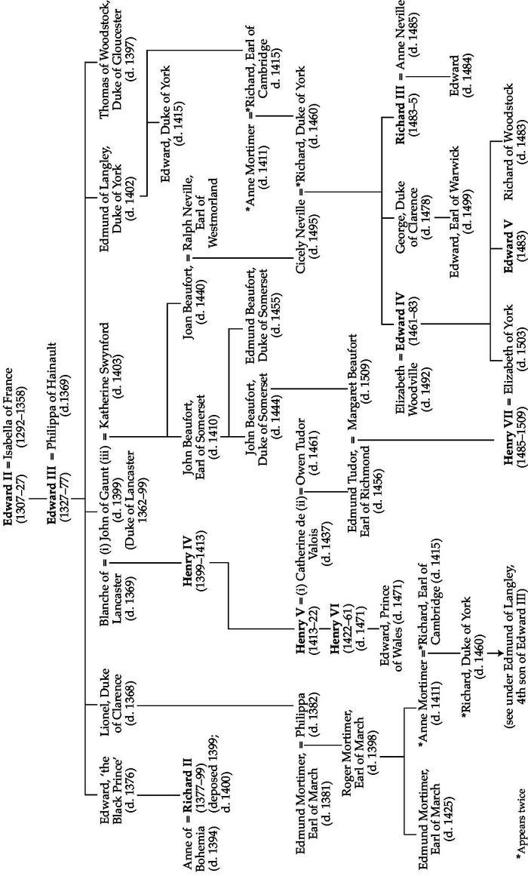

3. Genealogy of the Kings of England 13071509

THE ANGLO-SAXON PAST

By sundown on Saturday, 14 October 1066, events on a previously obscure Sussex hillside had decisively altered the course of English history, as indeed of world history. Surveying the scene of carnage, even those eyewitnesses who could hope to gain most from the days events were appalled by what they saw. As William of Poitiers, in all likelihood a chaplain attached to the army of the Duke of Normandy, later put it, Far and wide the earth was covered with the flower of the English nobility and youth, drenched in blood. Pitched battles were rare events in the Middle Ages. Too much could turn upon a single moments hesitation, upon false rumour or an imperfectly executed manoeuvre. Only if prepared to gamble with fate, or absolutely certain of victory, would a general commit himself to battle. William of Normandy did precisely this in October 1066, not because he commanded overwhelming odds or could be certain of Gods favour, but because he had just staked the wager of a lifetime. By crossing the Channel with a vast army of Frenchmen, not only his own Norman followers but large numbers of knights and mercenaries from as far north as Flanders and as far south as Aquitaine, he risked everything on a single roll of the dice. Should his army fail in battle, should the enemy refuse combat, cut off the possibility of retreat and leave the French to stew in their own mutual recriminations, then William would go down in history as one of the most reckless gamblers of all time. As it was, his outrageous manoeuvre succeeded not so much through his own skills but because of the hubris of his enemies.

The English commander, Harold Godwinson, had just celebrated victory in the north of England, having butchered an entire army of Norwegian invaders at the Yorkshire settlement of Stamford Bridge on 25 September. Clearly, God was an Englishman, and Harold was Gods appointed instrument. In these circumstances, when news reached him of the landing of Williams army at Pevensey, three days after his victory, Harold packed up his troubles and marched his army southwards for what he clearly expected to be yet another great celebration of English martial superiority. Not for the first time, nor the last, a sense of manifold destiny and of the invincibility of England in the face of foreign threat, lured an English army onwards to disaster.