Copyright 2013 by Rickey Vincent

Foreword copyright 2013 by Boots Riley

All rights reserved

First edition

Published by Lawrence Hill Books, an imprint of

Chicago Review Press, Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-61374-492-5

All lyrics of original Lumpen songs transcribed herein are copyright the original authors and are used by permission.

No More, Power to the People, The Lumpen Theme, People Get Ready, For Freedom, Bobby Must Be Set Free, Ol Pig Nixon, Revolution Is the Only Solution 1970 by W. Calhoun.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Vincent, Rickey.

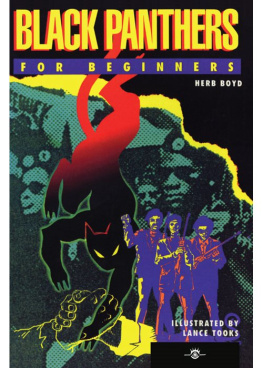

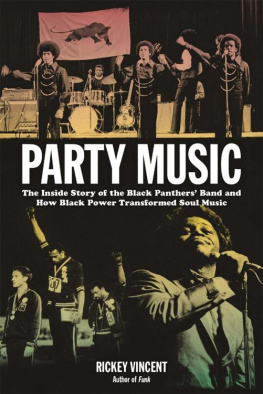

Party music : the inside story of the Black Panthers band and how black power transformed soul music / Rickey Vincent. First edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61374-492-5 (trade paper)

1. Lumpen (Musical group) 2. Rhythm and blues musicPolitical aspectsUnited StatesHistory20th century. 3. Soul (Music)Political aspectsUnited StatesHistory20th century. 4. Black powerUnited StatesHistory20th century. 5. Black Panther Party. I. Title.

ML421.L84V56 2013

781.6440973dc23

2013026033

Cover design: John Yates at Stealworks

Cover photographs: top, Lumpen onstage, Bill Jennings; left, Smith and Carlos at 1968 Olympic medal ceremony, Time Life Pictures/Getty Images; right, James Brown, Pierre Fournier/Sygma/Corbis

Interior design: PerfecType, Nashville, TN

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

For Gary

Contents

Index

Foreword

C ontrary to popular belief, some of the most heated debates between revolutionaries are about music. People with the supposedly unlikely dream of changing the whole world love talking about music. Perhaps this is because when youre listening to music, the whole world seems to be summed up for you in an earful of melody and rhythm.

During the 1920s, musical artists close to or in the Communist Party USA were debating the most effective music to accompany the militant strikes, shut-downs, and factory occupations that were happening as a result of their organizing efforts. According to the book Folk Music and The American Left by Richard Reuss, composers like Charles Seeger (Pete Seegers father) were arguing the position that folk musicalthough popularwas largely apolitical and was not a suitable vessel for revolutionary messaging. It was considered apolitical at the time. They argued that the style most suited to revolution was a more symphonic approach, reminiscent of the Romantic Era music that bore the Internationale. After all, this was the music of the European left, where revolutions were happening. The folk music side of the debate was a logical onefolk music was the music that the people were listening to. This is where they needed to be. Composers like Charles Seeger were eventually won over and became an advocate and producer of revolutionary folk music.

This same debate was happening in the 1990s among folks looking for a way to connect hip-hop music with social movements. The argument was that a certain style of hip-hopthe hip-hop that most people listened to, the hip-hop with more of a blues or funk aestheticwas base and ignorant, and that the more jazz-influenced aesthetic lent itself to a certain consciousness. I never agreed with this argument, as many of the artists who fell into the conscious hip-hop category talked about the same things gangsta rap did, but with a different style and with less substance about the trials and tribulations of life. Furthermore, folks like Ice Cube were making some of the most politically revolutionary music of the early 1990s, but were called gangsta simply due to their funk/blues aesthetic. Later, the group Dead Prez would prove the conscious crowd wrong by making the song (Its Bigger Than) Hip-Hop, which combined Southern-style crunk aesthetic with lyrics about getting the po-pos off the block. The song was played all over the countryon radio, in clubs, in Delta 88s and coffee shops.

Ive heard much talk from radicals about how we must create a new revolutionary culture, as if the problem with the culture that people are consuming is not the culture, but the style. Ive been to countless meetings in which people were consumed with how to create drum circles in certain neighborhoods as a service to the community, while overlooking the fact that ten to twenty people gathered every day by the car with the loudest system and danced or rapped with the music. This schism existed in the 1960s and 70s as well, of course, with some believing that music wasnt really revolutionary unless folks were dressed in dashikis and playing congas.

The gist of the argument has to do with what people see as the primary need in the community. Do people need a cultural changemeaning, do they need to change their behavioror do they need to be part of a movement that makes material changes in their standard of living and relationship to the wealth they create? If you, as I do, see the latter as the answer, then you understand that the culture that exists is the one we need to harness. The aesthetic is fine. Its the content that needs changing. Yes, there are revolutions and rebellions happening around the world, and we can be inspired by thatbut we need to identify with ourselves, as we are now, as powerful vessels of change. Cultural change is guided by material change.

The Black Panther Party was also of the mind that material change was what was needed. The Black Panther Party put forward a serious class analysis that didnt waste time with the idea that changing the culture was the key. So, it follows logically, that when they decided to have a band, it would be a funk band. The Lumpen took the music that black folks in the United States were listening to at the time and changed the lyrics to make revolutionary agitprop grooves. The Lumpens music, like the Panthers themselves, pointed to the idea that there is no need to call on the us we could be, the us that we are just needs the right map and the right tools. Rickey Vincent just put a very important part of the map in your hand.

Boots Riley, Oakland, July 2013

Preface

T his book explores the soul of the black power movement. It puts faces to the revolution and seeks to humanize the black revolutionaries of the day. This book is for anyone who recognizes the transformative soul power of James Brown but still cant find his name in their civil rights history book. It is for anyone who was fascinated by the fearless vision of change put forth by the leaders of the black power era and has wondered how those ideas came about.

This idea has been in the works for many years. One event, perhaps, sparked the basis for this study. In 1988 my mother took me to a memorial for a local activist, Alameda County Supervisor John George, a stalwart community organizer and one of the most respected black politicians in the Bay Area. The humble, spectacled man was a tireless advocate for the working class, and he had died suddenly at the age of sixty. At the memorial, his daughter rose and spoke eloquently of George, reminding us that he was a revolutionary that could dance.

That phrase stuck with me. A revolutionary that could dance? What did that mean? I always figured that revolutionaries were warriors for the people. Was this to mean that, for the most part, they could not groove with the people? Growing up in the Bay Area, revolutionaries were not hard to find. Militants, hippies, artists, communists: revolution was in the air in Berkeley in the 1960s. But there was always a mythology around the black revolutionaries, especially the Black Panthers. Unlike Michael Jackson, they were seen as fighters, not lovers.

Next page