Table of Contents

AUTHORS NOTE

We would have preferred to honor the memories of the suitcase owners by using their full names; unfortunately, confidentiality laws made that impossible. Instead, we have used their real first names and reluctantly chosen pseudonymous last names that reflect their ethnicities and national origins.

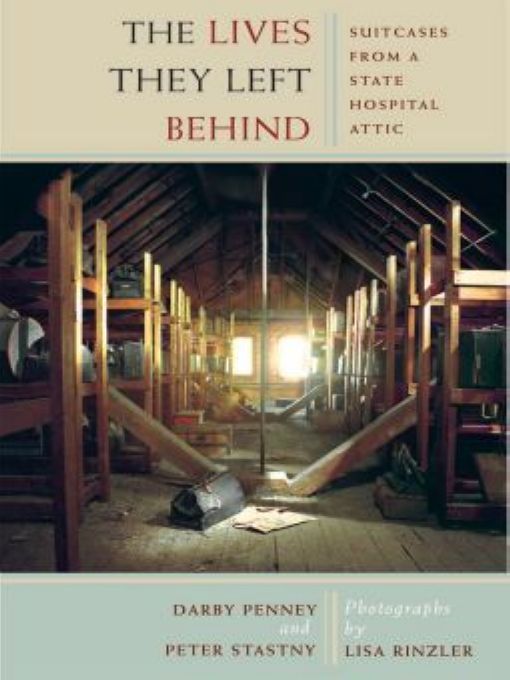

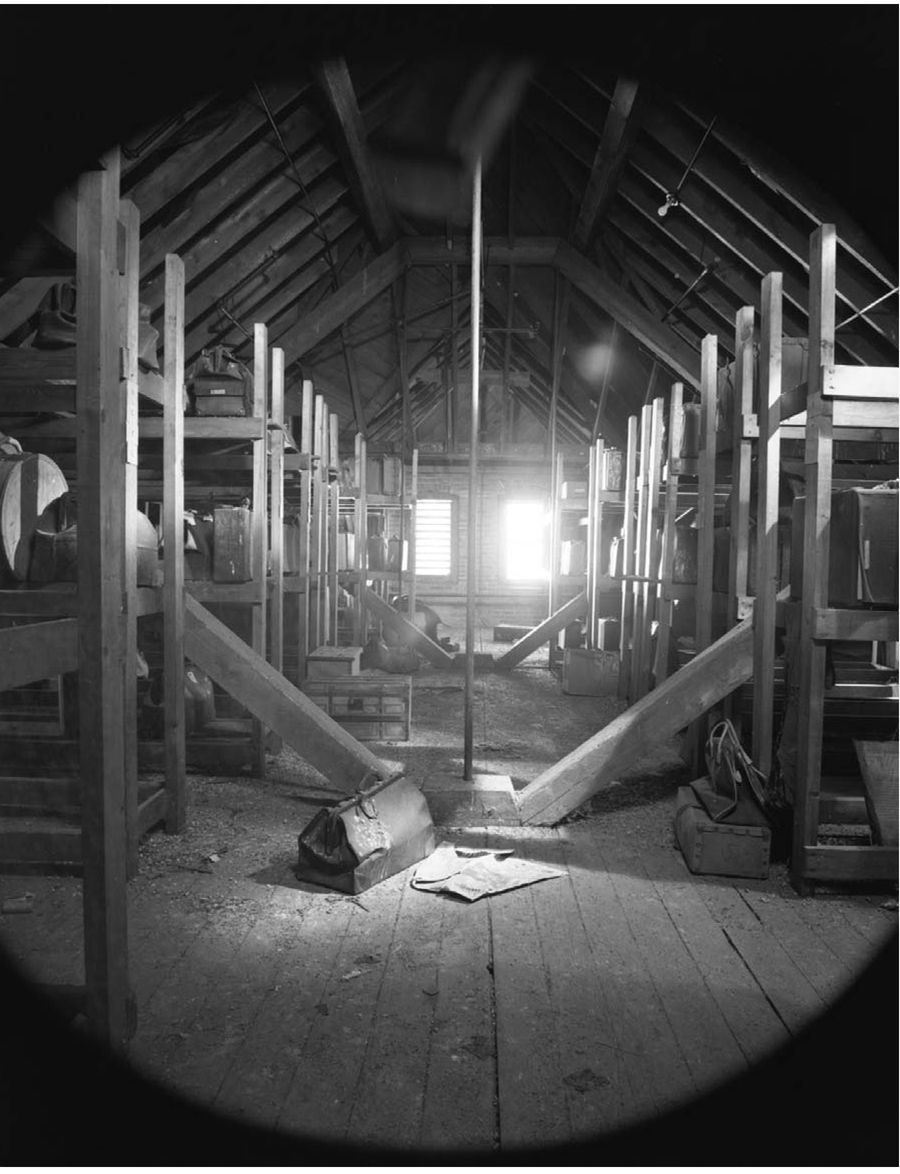

This book is dedicated to the memories of the Willard suitcase owners, and to all others who have lived and died in mental institutions.

FOREWORD

The literature on the history of our countrys treatment of people it considers mad basically consists of two types of books. There are histories that tell of the various medical therapies and types of institutional care that have been employed to treat those with mental and emotional problems over the past two hundred years, and then there are a handful of memoirs by current and former patients, nearly all of which raise troubling questions about the humanity of those treatments. The perspective that has always gone missing is an outsiders look, in the manner of a journalist or historian, at the lives of individual patients. What are their life stories? How did they end up in an asylum or mental hospital? How did the treatment change their lives?

Now we have such a book in The Lives They Left Behind. Through years of diligent research, Peter Stastny and Darby Penney have uncovered and documented the personal stories of people who spent decades at Willard State Hospital. Theirs is a stunning achievement, for they have written a book that bears witnessand in the most powerful manner possibleto a tragic time.

The history of our countrys treatment of people with mental and emotional distress is a troubled one. At the moment of our countrys founding, Benjamin Rush and other prominent colonial physicians utilized the modern treatments theyd learned about from their studies in Englandtherapies that were often extremely aggressive. The prevailing thought was that those deemed mad, by virtue of the fact that they had lost their reason, had descended to the level of a beast, and so English mad doctors had long advised that the insane needed to be tamed and weakened. Rush bled his patients profusely, and kept them tightly bound in a tranquilizer chair for long hours, this latter treatment hailed for making even the most irascible patient gentle and submissive.

Around 1800, Quakers in York, England, upset with such harsh therapeutics, pioneered an alternative form of care known as moral therapy. The Quakers reasoned that while they didnt know what caused madness, those who were suffering were still brethren and should be treated as such. They built a small retreat in the country, where they sought to treat their patients with kindness and provide them with shelter, good food, and companionship. Quakers in Boston, Philadelphia, and other cities soon built similar retreats, and modern historians have concluded that this form of gentle care worked well: more than 50 percent of the newly insane would be discharged within a year, and in the best long-term study of moral therapy that was ever done, researchers reported that 58 percent of those so discharged never returned to a hospital again.

The success of moral therapy ironically led to its downfall. Dorothea Dix, a nineteenth-century reformer from Massachusetts, lobbied state legislatures to build state asylums to provide this care to all who needed it, only once they did, cities and towns began dumping all sorts of people into these facilities. Elderly people, those with syphilis who had end-stage dementia, and those with incurable neurological disorders joined the newly insane in these mental hospitals, which grew ever larger and more crowded. Discharge rates naturally fell as this happened, and by the end of the century moral therapy had come to be seen as a failed therapy, asylum doctors having forgotten how, only fifty years earlier, it was common for the newly insane to recover and to never be rehospitalized.

This brings us to the period that is the subject of this book: 1900 to 1950. It is, in some ways, the darkest period in American history in terms of our treatment of people diagnosed with mental illness.

As the twentieth century dawned, America was falling under the sway of eugenic conceptions of mental illness. Eugenicists argued that if a society wanted to prosper, it needed to encourage those with good germ plasmthose the eugenicists deemed the fittestto breed, and to discourage those with bad germ plasm from having offspring. Those deemed mentally ill were naturally seen as among the most unfit, and so eugenicists argued that they should be segregated in mental hospitals. The hospital was no longer seen as a refuge for troubled people, but rather as a place for keeping them away from society during their breeding years so they would not pass along their bad germ plasm. Eugenicists also touted the notion that insanity was a single gene disorder, and thus it was hopeless to think an insane person could ever recover.

As a result of these eugenic beliefs, mental hospital discharge rates plummeted. Whereas more than half of the newly diagnosed treated in the early moral therapy asylums would be discharged within a year, patients in the first half of the twentieth century spent decades in state mental hospitals. For instance, a 1931 study of 5,164 first-episode patients admitted to New York hospitals from 1909 to 1911 found that over the next seventeen years, only 42 percent were ever discharged. The remaining 58 percent either died in the hospital or were still confined at the end of that period. As a result, the number of people in state hospitals rose from 126,000 in 1900 to 419,000 in 1940. A person admitted to a state hospital during this period had every reason to fear he would never get out.

The Lives They Left Behind tells the life stories of ten of those people. The tragedy of that era is illuminated in this book in a way no statistics ever could. The photos are equally haunting, and together they document a time when those who struggled with their minds, and often for the most common of reasonsloss of a loved one, loss of a job, or the difficulties that came with being an immigrant in a strange landwere locked away in mental hospitals and then forgotten.

It is tempting to look back at that era and see only the shameful relics of a distant past. Today, we tell ourselves, we are much more humane in our treatment of those with mental health problems, and our therapies are better, too. Yet any close examination of our care today should give us pause. The World Health Organization has twice found that schizophrenia outcomes are much, much better in poor countries like India, Nigeria, and Colombia than in the United States and other rich countries. Moreover, the number of psychiatrically disabled people in the United States has increased from 600,000 in 1955 to nearly six million today, a statistic that shows we still do not have a form of care that truly helps people recover, and even suggests that we are doing something today that may actively prevent recovery.

Perhaps Darby Penney and Peter Stastny will turn their attention to that conundrum next. This book illuminates the tragedy of our treatment of those with mental and emotional problems during the first half of the twentieth century in a novel and unforgettable way.