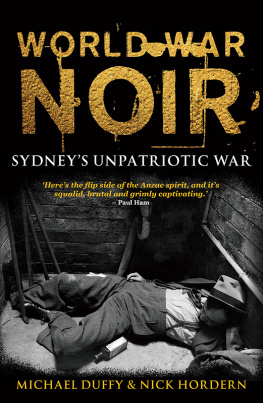

WORLD WAR

NOIR

MICHAEL DUFFY is the author of a biography of John Macarthur and crime books novels and non-fiction including Call Me Cruel, The Simple Death and Drive By.

NICK HORDERN is a former senior writer at the Australian Financial Review and has also worked as a political staffer, diplomat and intelligence analyst. He and Michael are the authors of Sydney Noir: The Golden Years.

WORLD WAR

NOIR

SYDNEYS UNPATRIOTIC WAR

MICHAEL DUFFY & NICK HORDERN

A NewSouth book

Published by

NewSouth Publishing

University of New South Wales Press Ltd

University of New South Wales

Sydney NSW 2052

AUSTRALIA

newsouthpublishing.com

Michael Duffy and Nick Hordern 2019

First published 2019

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to the publisher.

ISBN: 9781742236049 (paperback)

9781742244457 (ebook)

9781742248912 (ePDF)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia

Design Josephine Pajor-Markus

Cover design Nada Backovic

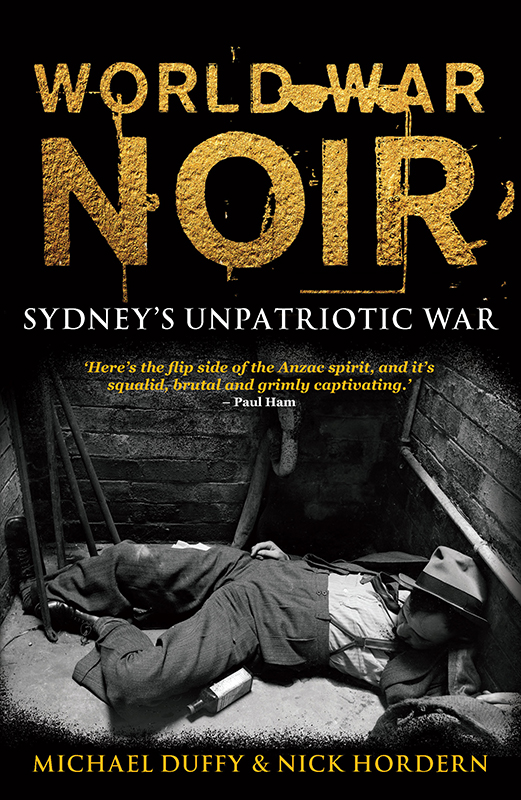

Cover image Corpse, late 1930s. Details unknown. NSW Police Forensic Photography Archive, Justice and Police Museum, Sydney Living Museums.

Maps Josephine Pajor-Markus

All reasonable efforts were taken to obtain permission to use copyright material reproduced in this book, but in some cases copyright could not be traced. The authors welcome information in this regard.

This book is printed on paper using fibre supplied from plantation or sustainably managed forests.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION: SYDNEY IN WARTIME

Australians have a certain idea of their country during World War II, an idea we can call the War Memorial view because it is embodied in the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. It includes the belief that during that war Australians men and women, military and civilians put aside self-interest and rallied wholeheartedly behind the war effort.

A lot of them did, but a lot didnt, and this book is mainly about those who did not. The unenthusiastic made up a large part of the Australian population during WWII and while they may not have deserved a War Memorial of their own, they would certainly have filled one.

During the war industrial unrest reached levels not seen since the 1920s. In the latter years of the war scores of thousands of service personnel were arrested for being absent without leave. The enormous amounts of money Australians gambled on horseracing much of it illegally soared at a time when the government was calling out for people to subscribe to War Loans. In the light of these and similar instances, the War Memorial view tends to overlook the diversity of reactions by Australians to the war. Not everyone believed their highest duty was to the country; some thought this was owed to their partner or to their family or to the international working class. Or to themselves.

This book is a prequel to our previous history of the citys underworld, Sydney Noir: The Golden Years, which covered the late 1960s. Between them, the two books form a sort of alternative history of the city, not just the story of the underworld but of its symbiotic relationship with the rest of society. While both books focus on crime, in World War Noir we have broadened the scope to describe more fully the society that the underworld fed off and supported. And of course wartime brought its own opportunities for those on the make.

A lack of patriotic zeal on the part of some during WWII shouldnt come as too great a surprise, because the preceding years had done little to foster it. Stepping into the shoes of an Australian in September 1939, the first thing that would strike you was that war had come cruelly hard upon the heels of World War I. If you take 2019 as a vantage point and adjust the numbers for the larger population, it would be as if in the late 1990s 400 000 Australian men had died and 900 000 had been wounded in the greatest war in all history. Then there was the Great Depression; it would be as if unemployment had peaked in 2012 at the Depressions 29 per cent, rather than the GFCs 6 per cent.

As a result of these twin disasters, authority was at a discount. People were more sceptical, both about the much-vaunted egalitarian, democratic nature of Australian society and about Australias place in the global confederation of the British Empire. Whether looking at home or abroad, the questions posed by the Depression and British policy towards Australia were similar. Were the interests of the individual the same as those of the country? Were the interests of Australia the same as those of Britain? Were Australians equals, or subordinates?

In 1938 Sydney had put these reservations to one side to celebrate its Sesquicentenary, the 150th anniversary of the arrival of the First Fleet at Sydney Cove. Dramatising the umbilical link to the Mother Country, on 26 January there was a re-enactment of the landing in Sydney Cove followed by a parade of motorised floats through the city. The pageant included Aboriginal people; activists held a Day of Mourning and Protest to coincide with the commemoration a campaign now cited as an early example of organised Aboriginal activism. But the pageant did not include convicts, an omission that ignored the criminal tradition that, acknowledged or not, has always lain at the heart of Sydneys identity.

Generally speaking, the Sesquicentenary was celebrated in a spirit of optimism. It had taken a long time, but the city was recovering from the Depression. And it was changing. In 1939 Australias population was a quarter of what it is today. Sydney was the biggest city in Australia with 1.28 million people, ahead of Melbourne, which had just over one million.

It was a very different Sydney to the one we know today. Photos from the time show streets in the suburbs as strangely deserted, with few people, trees or cars. Private vehicles were a rarity you could always find a parking spot in George Street and they became even scarcer during the war. The streets of the inner city were carpeted with cigarette butts. The bulk of households didnt have a phone and often the quickest way to communicate, even between nearby suburbs, was by telegram.

But the city had fine tram and rail networks the Harbour Bridge had opened in 1932 and residential construction was booming, with blocks of flats springing up in suburbs like Kings Cross and Kirribilli. Most of these new brick apartments were in the ring beyond the inner suburbs, which were distinguished by their damp terraces and air made foul by adjoining factories and workshops. The inner suburbs Glebe, Chippendale, Redfern, Surry Hills, Darlinghurst, Woolloomooloo were a poverty- and crime-ridden world unto themselves. They were where Sydney Noir lived, and where it died.

World War II would prove to be Sydneys closest approach to the actual experience of war. The perceived threat to the city would be underlined by the air raids on northern Australia and the Kokoda Campaign. We now know that the Japanese never intended to invade Australia, but in 1942 it was quite reasonable for the military authorities to think they would and more than half the Sydneysiders polled thought so too. It was a city in fear.