Contents

Come Together

Come Together:

the years of gay liberation

(197073)

edited and introduced by

Aubrey Walter

This edition published by Verso 2018

First published in Great Britain by Gay Mens Press 1980

Selection and Introduction Aubrey Walter 1980, 2018

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-237-6

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-238-3 (UK EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-239-0 (US EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

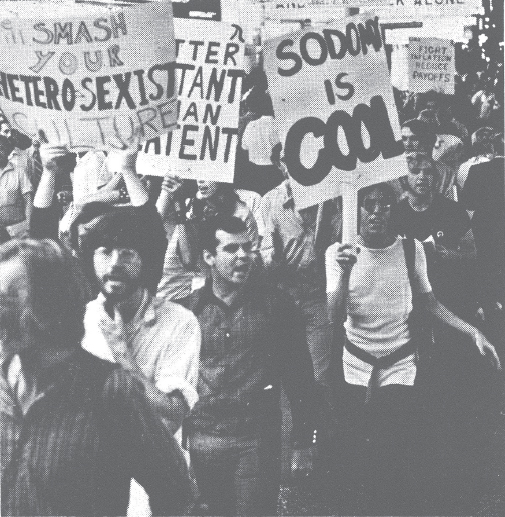

Printed in the UK by CPI Group

It is now common knowledge that the gay liberation movement started in New York in June 1969, when the queens in the Stonewall bar fought back police repression, and for the first time in history gay people began to stand up on a massive scale. The movement spread like a forest fire, first across the United States, then soon catching on in the rest of the Western world. In this intense struggle for the social recognition of homosexuality, a certain gay consciousness was formed.

The essence of this new consciousness was gay pride. Gay pride meant that the homosexual individual no longer accepted the heterosexist societys definition of him/herself as criminal, pathetic or sick. It meant that at long last the lesbian and gay man could raise their heads with the deep inner conviction that homosexuality was part and parcel of the human package, seeing the roles imposed on women and men by the present sexist society as perverse, rather than the homosexuals who reject them. The growth of gay pride could only be a collective process. Only if gay people gained strength from solidarity and organisation could they advance their liberation and spread the new message. And in this way countless numbers of lesbians and gay men gained the necessary courage and strength to come out of their double-life hellholes and closets and confront the straight world around them.

As the gay liberation struggle developed, the positive aspects of homosexuality became ever more clear. Unlike heterosexuality, homosexuality was already completely free from any connection with biological procreation. In the context of a sexist society, moreover, our sexuality was not based on the subjugation of one sex by another. Gay relationships were far less structured by male domination and the gender system, while in straight relationships the temptation to fall back into the gender pattern is overwhelmingly strong, no matter how intensely individuals try and fight against it.

The London Gay Liberation Front Manifesto of 1971 shows the high point reached by the new gay consciousness, a level which the gay movement of today, unfortunately, often fails to match:

Gay shows the way. In some ways we are already more advanced than straight people. We are already outside the family and we have already, in part at least, rejected the masculine or feminine roles society has designed for us. In a society dominated by the sexist culture it is very difficult, if not impossible, for heterosexual men and women to escape their rigid gender-role structuring and the roles of oppressor and oppressed. But gay men dont need to oppress women in order to fulfil their own psycho-sexual needs, and gay women dont have to relate sexually to the male oppressor, so that at this moment in time, the freest and most equal relationships are most likely to be between homosexuals.

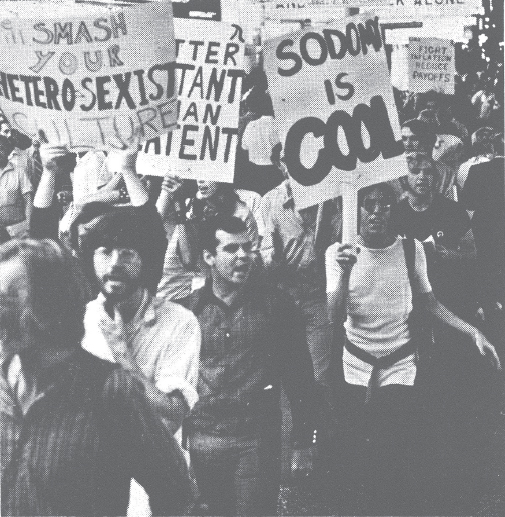

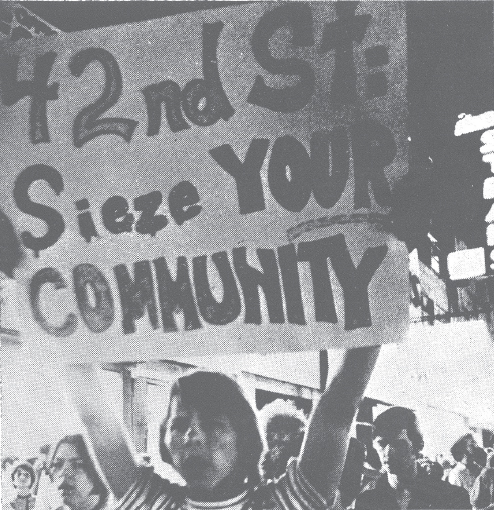

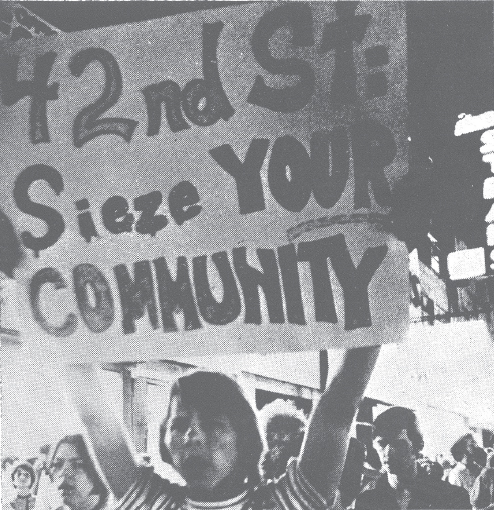

Starting in the USA, the new gay movement learnt from the struggles of many other oppressed sectors in Western society. It learnt from the struggles of the womens movement, from the black movement, and from the movement against the imperialist war in Indochina. It was comparatively simple for people in the gay movement to make connections between the oppression they met from the forces of law and order, and that dealt out to other sectors. So, even though the gay movement always insisted on being fully autonomous, it could easily see itself as part of the wider struggle for full human rights and liberation.

In practical reality, however, the connection with other movements was not so easy. Many sectors of the radical movement opposed gay liberation, indeed most of the traditional left organisations initially saw homosexuals as mere decadent excrescences on the body politic. Large sections of the womens movement were also sceptical and antagonistic at first, because at the turn of the 1970s lesbianism was only just becoming an issue in the movement and there was no adequate theory of sexism and gender. But by its tenacity, its militant activity, and by showing the courage of its convictions, gay liberation gradually began to whittle away opposition from the rest of the radical movement, even if its full significance is still very far from generally understood.

The Birth of London GLF

During the first year of GLF in the United States, most gay men and lesbians in Britain were unaware of what was happening on the other side of the Atlantic. There were very occasional reports in the press, such as in spring 1970 when gay liberationists disrupted a psychiatric conference in San Francisco. About this gay man Konstantin Berlandt running round in a red lame dress and long wig, as one of a group of gay guerillas protesting the treatment and definitions of homosexuality by the US psychiatric establishment. It was intriguing for me to read these reports, but very hard to fit them into my ideas about politics, especially politics in England. When I visited North America in summer 1970, one of my main objects was to find out about the new gay movement. I stayed with GLF groups in one city after another, and it really changed the way that I looked at my own homosexuality, and the question of gender in general. It was there that I got to know Bob Mellors, who was hanging out with New York GLF. We met at the Revolutionary Peoples Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, called by the Black Panther Party. Not only did gay liberationists go to Philadelphia to show solidarity with the black movement, but it was here that Huey Newton, as leader of the Panthers, first gave clear support to the gay cause, saying that homosexuals were maybe the most oppressed people in American society, and could well be the most revolutionary.

Bob Mellors and I decided that when we got back to London we would call a meeting to organise a GLF there. During that summer, however, the first sparks of the new gay consciousness were already beginning to fly in Britain. A gay freak, Dave Burke, wrote to the California newspaper