Contents

Guide

Page List

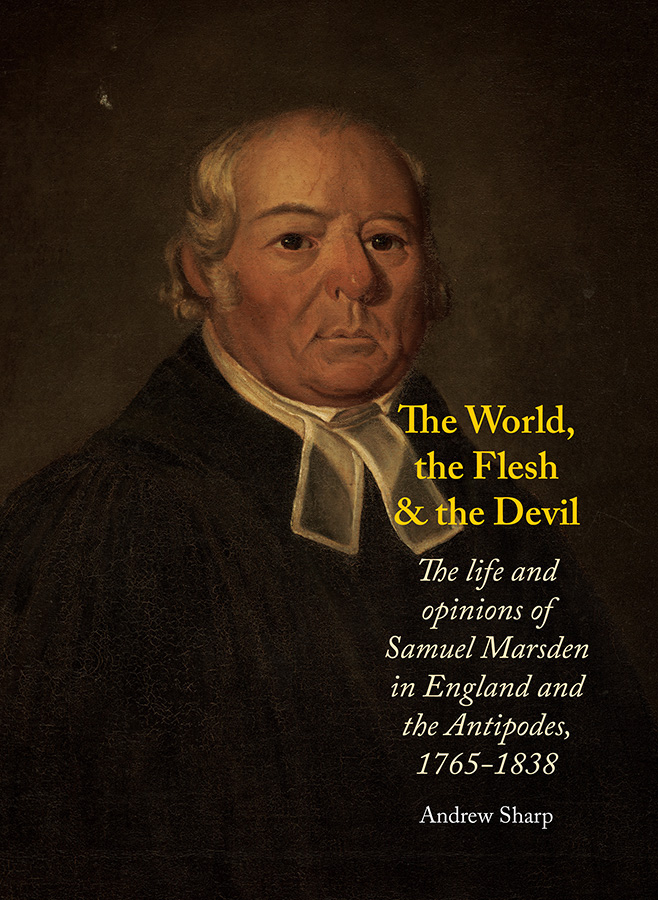

Andrew Sharp is an Emeritus Professor of Political Studies at the University of Auckland. Since 2006 he has lived in London, and is the author or editor of books including Political Ideas of the English Civil Wars 16411649 (1983), Justice and the Mori: The Philosophy and Practice of Mori Claims in New Zealand since the 1970s (1990, expanded 1997), Leap into the Dark: The Changing Role of the State in New Zealand since 1984 (1994), The English Levellers (1998), Histories, Power and Loss: Uses of the Past A New Zealand Commentary (2001, with P. G. McHugh), and Bruce Jessons To Build a Nation: Collected Writings 19751999 (2005).

The World, the Flesh & the Devil

The life and opinions of Samuel Marsden in England and the Antipodes, 17651838

Andrew Sharp

INTRODUCTION

The life and opinions of Samuel Marsden

In the Book of Common Prayer, which in its 1662 edition laid down the order of church services for the Church of England, the priest and congregation were ordered to pray to their God each day to protect them from the three enemies of the soul: the world, the flesh and the devil. Samuel Marsden, an ordained priest of the Church, went further than the Litany. He not only prayed for protection from that evil trinity but assailed them as often as he came across them sometimes subtly, sometimes in his blunt country Yorkshire way, sometimes alone, sometimes in concert with like-minded activists. Whenever he found men or women too much attached to the power and pride of life in the world he criticised them for not attending to their spiritual duties of seeking and loving God. Whenever he found them indulging in the pleasures of the flesh such as fornication, adultery, and drunkenness, he excoriated them. Wherever he uncovered crimes against the laws of man (like theft or murder or adultery or disobedience to superiors) or sins against the laws of God (like theft or murder or adultery or disobedience to superiors), there he saw the presence of Satan: he who was otherwise called the devil, the Prince of the Air, the Prince of this World or the Prince of Darkness. Satan would have mankind sin and suffer, in the biblical phrase, the wages of sin (Romans 6:23), namely death. Christianity, the religion binding mankind to God the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit the Holy Trinity would have them obey God and live eternally.

Marsden was a Christian evangelist. He would convert as many men and women as he could; he would cause them to be reborn and live. For him, St Paul, the Apostle to the Gentiles, was the most authoritative of Christs Apostles. In one of his many sermons as a chaplain in the British convict colony of New South Wales usually simply called by its inhabitants the Colony he spoke to the few who were reborn of what it was to be unregenerate. He used Pauls own words:

In time past ye walked according to the course of this world according to the prince of the power of the air, the spirit that now worketh in the children of disobedience [Ephesians 2:13]. The Apostle declares here that they were wholly under the government of Satan, who is called the prince of the power of the air. The same is the awful state of all unconverted men tho they know it not, and when this solemn truth is told them they will not believe it, but spurn the idea.

It was too easy for the unconverted to reject the gospel of salvation. There was hope, however. They could be redeemed if they repented of their sins and came to believe that Christ was the Son of God come to earth in the flesh to save them. Then they would not be among those punished with death and hell by an avenging God. They would join the blessed in heaven and live eternally. Thus said St Paul; thus thought Samuel Marsden.

But he saw himself not only as a Christian evangelist preaching salvation through Christ. He also saw himself as a minister of the Church of England; and so besides often irritating even enraging non-believing sinners by admonishing them and making evident his disgust at their behaviour, he found enemies in other Christian churches. He was a dedicated Protestant, opposed to the idolatry of the Papist Roman Catholic Church. He thought Romes dedication to representations of spiritual realities in idols constructed from mere earthly materials was straightforwardly sinful because it was prohibited in the Word of God. The Second of the Ten Commandments in the Holy Bible forbad it. Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth: Thou shalt not bow thyself down and serve them (Exodus 20:45). He thought too, that Romes overmuch dedication to worldly ceremony and formality discouraged vital religion, the product of the immediate experience of the believer. The rites of Rome, unlike those of England, were not helps to salvation but impediments. On the other hand, as a priest of the Church of England, though he often worked wholeheartedly with Presbyterians, Methodists of various kinds, Congregationalists and Quakers for the salvation of unbelievers, he could not enter into all their beliefs. He did not mind much about abstruse theological differences among the Protestant denominations, but he could not admire their discipline (i.e. their organisations) or certain of their more egalitarian and antiauthoritarian doctrines. For instance, he could not stomach any idea of the social and political equality of all believers or the idea that the Holy Spirit might speak direct to ones conscience against the teaching of the Bible. If either of these doctrines were true, then a most horrible prospect no man or woman need obey any other. Dangerous enthusiasm was to be distinguished from a lively faith derived from the Bible.

And so Marsden ran into continual opposition when he took up his pastoral duties in the Colony in 1794. He ran into opposition in the South Seas too. Though he was not a missionary himself except at times during his seven visits to New Zealand, he was a leader of Protestant missionaries to the heathen savages and barbarians among scattered islands of the vast South Pacific Ocean. During the first years of the nineteenth century he became the New Holland agent of the interdenominational Missionary Society and of its missionaries in the Society Islands centring on Tahiti: the supreme example of his willingness to work with nonconformists and dissenters for the salvation of souls. As he saw it, it was not essential that the Society should be made up exclusively of members of the Church of England, or its members precisely conform to its doctrine and discipline if they were to save the souls of the heathen. Salvation came with membership of the true, eternal, church, not with adherence to any particular gathering of believers in the world. Later, though, from 180810, he took the lead in planting a Church of England mission in New Zealand, and was appointed the agent of the Missionary Society for Africa and the East. He felt more at home working with that society, though he never deserted the other.

By about 1806 the Missionary Society, gradually shedding its Church of England members, took on the informal and then in 1818 the formal title of the London Missionary Society (LMS); in 1812 his own churchs society took on the name of the Church Missionary Society (CMS), though it, too, had informally used its later title rather earlier than that. Marsdens name became prominent in the annals of both societies. As their agent he suffered minor clashes with the missionaries of the Missionary Society over their extravagance, and their misbehaviour gave ammunition to the enemies of missions in New South Wales. But his problems with the New Zealand mission were far greater. He was much more central in planning and executing its operations than he was to the Missionary Society, and was more authoritarian a leader out of necessity. Like any man, he was inevitably imperfect in formulating and executing plans, but those who disagreed with him easily converted their disagreements about policy into challenges to his authority over them and aspersions on his character.

Next page