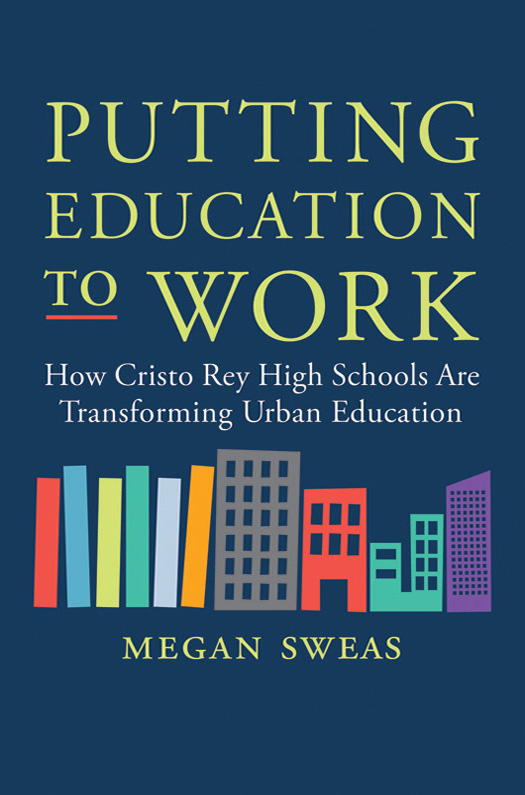

This book is in some ways a follow-up to the first book written about Cristo Rey: More Than a Dream by G. R. Kearney, which told the story of how we started the first Cristo Rey school. One important idea from the start of Cristo Rey Jesuit High School in Chicago in 1996 was that the corporate work-study program was started solely to help pay the bills so that students from families who could not afford it could attend a Catholic college-prep high school.

We did not appreciate until later how working in a law firm or hospital or insurance company would transform our students and make them aspire to something greater, both in high school and in college.

That has been the greatest gift of Cristo Rey. It has captured the imagination not only of the students but of executives and employees at more than two thousand companies who want to see youth from the inner city become skilled members of the workforce. It has led forty university partners throughout the country to collaborate with Cristo Rey because our graduates help them meet their missions.

Cristo Rey has become a national movement that is inspiring school reform throughout the United States. Our job skills training program is even inspiring those who serve the poor around the world, from Fe y Alegra schools in Latin America to refugee schools in South Sudan.

More Than a Dream focused on one Cristo Rey school, the first one. This book tells the story of how that one school led to the opening of twenty-eight schools now serving more than eight thousand students. All of these schools share the same missionto transform urban America one student at a time.

John P. Foley, SJ

Founder of the first Cristo Rey Jesuit High School and first president of the Cristo Rey Network

Contents

A senior at Cristo Rey Jesuit College Preparatory School in Houston, Texas, Matias Esparza is lanky, with thick black hair and thin-rimmed glasses. On first impression, he seems unassuming and nerdy, speaking quietly while his classmates joke and laugh around him. But he is also a leaderthe type of student who not only earns good grades, but also tutors his classmates. When he gets up on the stage to deliver his valedictorian speech at the schools inaugural graduation, he is greeted by the enthusiastic applause of his classmates and more than a thousand guests.

Although there are Cristo Rey Network schools in many cities around the country, Houston has wholeheartedly embraced the Cristo Rey model of Catholic education. The school has raised more than $20 million, and it receives 400 applications a year for just 160 spots.

The entire city seems to be at the graduation too. The Bayou Music Center is set up to seat thirteen hundred, and only the back corner is not full. Many families arrived more than an hour early and waited patiently in the Houston heat, so that they could stake out general admission seats just behind the graduates. Corporate sponsors and well-heeled supporters deferred to the families, filling in the back sections. Latecomers filed into the balcony, though the school had not planned to use it.

On a stage typically reserved for rock stars, Matias stands tall in the bright lights and greets the dignitaries on the stage. He looks comfortable in his black gown, yellow cape, and black mortarboard, casually brushing back the tassels that keep falling in his eyes.

He starts his speech with a quote. When she was just a girl, she expected the world. But it flew away from her reach. So she ran away in her sleep and dreamed of para-para-paradise, he says, slowing the final word. Then, in a low baritone, he begins to singa cappella: Para-para-paradise, every time she closed her eyes.

The crowd laughs and shouts while Matias smiles onstage. As the applause ends, Matias takes a serious tone. He can relate to the girl in his favorite song, Paradise, by the band Coldplay, which has played on the same stage. As a boy, he thought his mom could provide all the toys he and his younger brother wanted. Then, he says, the concept of money and the reality that we did not have any sank into my childish brain. I knew that no matter how hard I worked, paradise would be just out of my reach. For Matias, paradise was education.

It is an all-too-common narrative in inner-city neighborhoods. As a journalist who has both worked with youth at urban schools and written about the challenges they face, I have seen too many young people whose dreams seem out of reach. Others do not even dare to dream. At a public high school close to Cristo Rey Jesuit, fewer than 60 percent graduated in 2010, and of those only 14 percent were ready for college.

A number of Matiass classmates are sure they would have ended up dropping out of high school if they had gone to a public school. Even Matias says he did not aspire to college as a high-school freshman. But the Cristo Rey model of education is changing the narrative. Thanks to his high school, Matias has found his paradise: he has a full-ride scholarship to Rice University.

The inaugural graduation in Houston celebrates the sixty individual success stories of Matias and his classmates, but the graduates also know that they are part of a bigger story. Their graduation day also represents the culmination of lessons learned over the history of the Cristo Rey Network.

AN INNOVATIVE EXPERIMENT

In Houston and across the country, Cristo Rey Network schools have helped thousands of boys and girls realize their potential. With twenty-eight schools and counting, this model of urban Catholic secondary education has come a long way since the first school opened in Chicagos Pilsen neighborhood in 1996. Back then, the schools first classes were taught in the corners of the gymnasium in a former Catholic grammar school.

Today, Cristo Rey schools still make their home in a variety of school buildings, some in better shape than others. The decrepit state of the school in Houston was a blessing in disguiseit was cheaper to rip out its institutional brick, giving its hallways a hip, loftlike feel. In Newark, students repainted their classroom walls in cheery colors, though green institutional brick still lines the hallways.

In Boston, the former Catholic grammar school feels small for teenagers, but the hardwood floors and white walls have lasted more than a hundred years and look as though they will last another hundred. In Waukegan, Illinois, meanwhile, the school building is falling apart. When the president says they are on a sinking ship, he means it literally, pointing to where the floor has sunk below a door frame. At the other end of the spectrum is Cristo Rey Jesuit High SchoolTwin Cities, which hardly looks like a school, with its glassed-in atrium and flexible teaching spaces. It shares its facilities, including a huge gym and state-of-the-art auditorium, with a youth center called the Colin Powell Center.

Along with their physical differences, the schools have their own unique populationsfrom Mexican immigrants in Chicagos Pilsen neighborhood to African-Americans on the same citys West Side. Boston has Dominican immigrants, and the Twin Cities have Somali Muslim refugees. Some schools compete for students with high-performing charter schools. As in Houston, many schools are surrounded by public schools with high dropout rates. Newer Cristo Rey schools tend to be found in states with school-choice programs.

Despite different appearances and obstacles, schools look for similar qualities in students. Although each student has his or her own unique story, Cristo Rey schools enroll students who are from low-income families, are behind in school, and are uncertain about their future. Four years later, students graduate confident and college ready. The schools boast a 100 percent college acceptance rate for seniors, and the vast majority of graduates matriculate at two- or four-year institutions within a year of high school, at rates equal to those of the highest-income Americans.