C ONTENTS

My thanks go to a number of people who have made available source material and images, without whom this book would not have been possible.

They include: the staff and volunteers of the Guildford Institute (manager Trish Noakes, deputy manager Jan Todd, librarian Pam Keen and volunteers Graham Hadley and Chris Fitton) who allowed me access to its unique archives of scrapbooks from the period in question. They include Scrapbooks F and G and the Great War Scrapbook. These priceless books were compiled 100 years ago and contain local newspaper cuttings, pamphlets, leaflets, posters, photographs and so on.

I would also like to thank the former curator of Guildford Museum, Matthew Alexander, for his help and good advice; and Guildford Borough Councillor Terence Patrick, for a useful insight into his grandfather, William Patrick, also a former mayor of Guildford, who worked so tirelessly for the town in many capacities during the First World War.

Thanks also to the curator of the Surrey Infantry Museum at Clandon Park, Ian Chatfield, for details on The Queens (Royal West Surrey) Regiment and for supplying photos of the 1st Battalion in 1914 and the football from the Battle of the Somme.

My good friend Martin Giles (who served in The Queens during the 1970s and 80s), for his research on the Parson brothers from St Catherines Village who both died on the Somme in 1916. I must also thank Martin and Mike Bennett; the three of us give an illustrated talk on the Zeppelin raid on Guildford in 1915. I also thank fellow local historians Frank Phillipson and Roger Nicholas for their research into Guildfords night of terror.

Thank you to another friend, Sarah Bennett, who has researched and written about the Guildford Division of St John Ambulance, including its work during the First World War; and also Les Knight, a former St John superintendent at Guildford, who has a superb collection of photos of the division.

From postcard collection and dealer Tim Winter of Haslemere, I have purchased a number of cards that have been used in this book. Tim also kindly allowed me to photograph a diary/picture book he has in his collection that was compiled by a nurse at the Red Cross Annexe a war hospital that occupied the County School for Girls in Farnham Road. A couple of pictures are featured in this book.

The Spike Heritage Centre in Warren Road tells the story of the Guildford Union Workhouse which, during the war, was used as a military hospital. The Charlotteville Jubilee Trust administers the Spike, and my thanks go to its chairman John Redpath and dedicated volunteer Jane Thomson, for useful historical details.

I thank Ian Nicholls and his partner Julie Howarth, and Nigel and Val Crompton, who visited me for an afternoon of great conversation about the First World War. Ian has researched the men from Charlotteville named on the war memorial in Addison Road, and Val has family members of the Newman family named on it. Nigel, meanwhile, is a member of the Western Front Association.

Jim Parker and his family gave me details of two members of the Knight family commemorated on the Burpham war memorial.

Fellow bottle collector and historian John Janaway and I (with others) have, with permission from James Giles, the Natural England ranger for Rodborough Common, been given access to investigate the site of the former Witley Camp, a training centre for thousands of soldiers during the First World War. I salute them for the ongoing days we are spending exploring this site.

Dan James took the aerial photograph of St Marthas church, while John Glanfields research into the wartime manager of the Chilworth Gunpowder Mills has proved very useful.

Marion May collects period costumes and kindly allowed my daughter to model a wedding dress dating from the time of the First World War, and which is featured in this book.

Some snippets of information came to me third hand, so to speak. So may I thank those unknown sources.

Many thanks to my wife Helen for reading the text and making vital comments on it. This book is dedicated to her and our daughter Bryony who, I am pleased to say, is developing a healthy interest in history.

And last but by no means least, to William Oakley, the editor of the Surrey Advertiser at the time of the First World War. Like a true local journalist, he must have been known to many Guildfordians at the time. After he retired he wrote the book Guildford in the Great War (1934). It is twice the length of this book and worth reading for anyone who wants to learn more in-depth facts about the town between 1914 and 1918. In it he apologises for its lack of photographs (production costs being the reason). I am happy to say that this is not the case here due to modern publishing techniques, courtesy of my publishers, The History Press.

The sound of war can be heard in the strangest of places even far from where the battles are raging. It was an afternoon two years into the Great War and the officer in charge of the men guarding Chilworth Gunpowder Mills walked up to St Marthas church on the hill nearby. Boughs and bushes covered the church in case the crew of a German Zeppelin recognised it as a landmark while seeking to bomb the works below, where men and women were busily making cordite for the war effort.

The sound of guns firing on the Western Front were heard at St Marthas church.

The officer, writer and naturalist Eric Parker, stood with his back to the south door of the church and to his amazement he could hear the guns firing in France a distance of perhaps 150 miles as the crow flies. He later wrote that he could clearly hear heavy guns, the shaking boom, the rattle of musketry as if we were fighting Germany in the next parish. It came, he said, in repercussion of sound from the large oak door. He stepped a yard to the side and was in the silence of the Surrey countryside; a yard back to his right and he was in France.

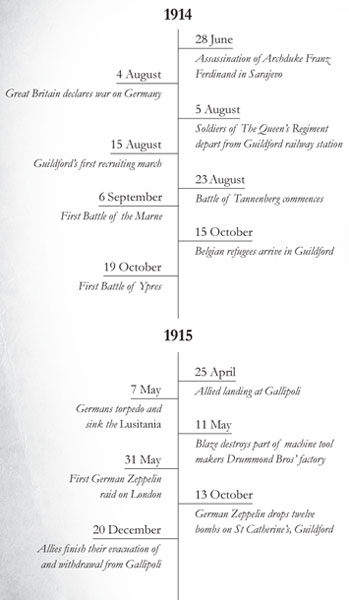

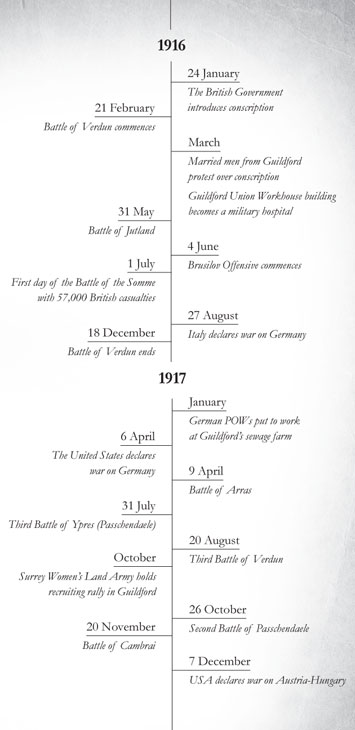

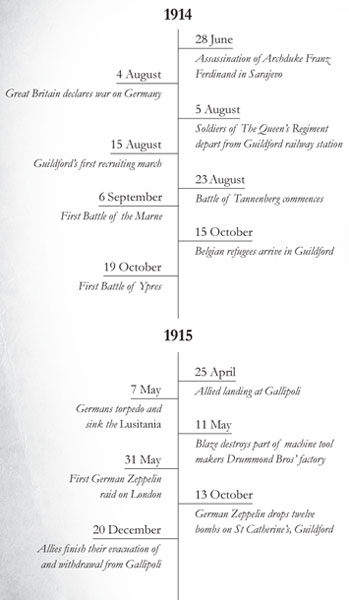

This strange occurrence may have brought the actual sound of war to Guildford, but in another sense it was here all the time from 4 August 1914 to 11 November 1918. Like every other community in Britain, Guildford felt the effects of the war. Not just because of the 500 or so men from the town who died on active service, but also in how much daily life changed. The home front in Guildford had to get used to: a military presence like it had not witnessed before; fears of German spies in their midst; food shortages that eventually led to rationing; the continued call for men to enlist until it became compulsory in 1916; women taking jobs left vacant by men who had gone to war such as working on the land and making munitions, or volunteering as nurses and helping at a number of war hospitals in the area.

Councillors and other important people in Guildford worked extremely long hours, sitting on committees and playing their part in formulating plans for the organisation and well-being of the town for the duration of the war. Indeed, the actual horror of warfare came very close on the night of 13 October 1915, when a Zeppelin hovered over the town and dropped twelve bombs across St Catherines Village, a mile from the town centre.

Next page