ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am deeply grateful to everyone who spoke with me for this book. Their accounts of their experiences as students, educators, parents, and community leaders were vital to my understanding of the last fifty years. Several sat for more than one interview, pointed me toward other sources, or provided documents. My sincere thanks to Anne Micheaux Akwari, Arkee Allen, David Anderson, Dave Balter, Ruth Balter, Jeanette Banker, James Beard, John Bliss, Carlton Brown, Luis Burgos, William Cala, Velverly Caldwell, Terry Carbone, Marlene Caroselli, Musette Castle, Ed Cavalier, Yalawn Christian, Frank Ciaccia, Walter Cooper, Jeff Crane, Archie Curry, Mark Allan Davis, Patricia DeCaro, Tate DeCaro, Susan deFay, Bob Duffy, Malik Evans, Mark Faegre, Jonathan Feldman, Anna Ferro, Deborah Gitomer, Mary Halpin, Bryan Hetherington, Kirk Holmes, Joan Coles Howard, Jasper Huffman, Kennedy Jackson, Bill Johnson, Wayne Johnson, Suzanne Johnston, Nellie King, Roy Lane, Jessica Lewis, Charles Marshall, Sereena Martin, Peter McWalters, Dana Miller, Joe Morelle, Nicole Morris, Idonia Owens, Nydia Padilla-Rodriguez, Amber Paynter, Dorothy Pecoraro, Jonathan Perkins, Don Pryor, Andrew Ray, Vera Richardson and her niece, Vera Richardson, Faust Rossi, Bob Sagan, Djinga St. Louis, Yvette Singletary, Lynette Sparks, Danny Speer, Bob Stevenson, Adam Urbanski, Thomas Warfield, Lovely Warren, Gloria Winston Al-Sarag, Lillie Winston, John Woods, and Alice Young.

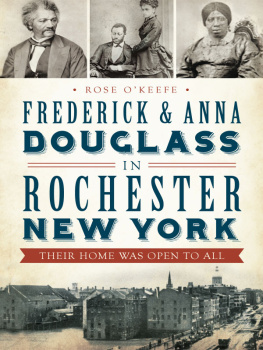

There is hardly a page in this book that does not contain at least one endnote pointing to a newspaper article. In Rochester as elsewhere, the unheralded daily work of journalists has been crucial in preserving local history. I thank and appreciate the many reporters, editors, photographers, and news assistants at the Democrat and Chronicle, the Times-Union, and other daily and weekly newspapers whose work is referenced in this book. Particular recognition is due to Frederick Douglasss North Star, Howard Coless Voice, and James and Carolyn Blounts about... time magazine for preserving news about Rochesters Black community that white-owned newspapers failed to capture.

I include my current colleagues at the Democrat and Chronicle in my gratitude and appreciation. They have been a source of support and encouragement in writing this book and an inspiration as we strive to fulfill our journalistic mission in trying times. Matthew Leonard was an early and trusted advocate. Executive Editor Michael Kilian has been a tireless champion of journalism that reveals, explains, and combats structural racism in Rochester, past and present. He granted me leave to work on this book and has encouraged me in myriad ways, including by publishing an early version of chapter 2 in the February 9, 2020, edition of the newspaper.

The Rochester city historian, Christine Ridarsky, and her staff of Jay Osborne, Emily Morry, Brandon Fess, Dan Cody, and Gabe Pellegrino cumulatively walked many miles fetching stacks of books and clip folders for me. They offered, only half joking, to arrange a private office and sleeping quarters for me in the Local History and Genealogy Division reading room of the Rochester Public Library; I declined, but regardless am deeply thankful for their help and hospitality over several years. A version of chapter 1 appeared in the Rochester Public Librarys journal: Racial Segregation in Rochester Schools: 18181856, Rochester History 78, no. 2 (January 2020).

Thank you to Jessica Lacher-Feldman, Melinda Wallington, and Autumn Haag, among others, for their repeated assistance at the University of Rochester Rare Books and Special Collections division at Rush Rhees Library, and to Stephanie Ball at the Rochester Museum and Science Center. Thanks as well to the staff who helped me at other institutions: the Rochester Municipal Archives; the Rose Archives at SUNY Brockport; the Project UNIQUE Papers at Nazareth College; the Big Springs Historical Society in Caledonia, New York; the New York State Archives in Albany; the Jerome and Ruth Balter Papers at Swarthmore College in Swarthmore, PA; and the Library of Congress in Washington, DC.

Joan Coles Howard, Conor Dwyer Reynolds, Mitch Gruber, Emily Morry, Idonia Owens, Christine Ridarsky, Chris Widmaier, and Shane Wiegand all read portions of the book and offered valuable feedback; so, too, did the anonymous but appreciated peer reviewers who volunteered their time for Cornell University Press. Alana Kornaker cheerfully and skillfully drew the East High School enrollment boundary maps in chapter 3. Special thanks to Banke Awopetu for her feedback as well as her constant support and encouragement through the writing process.

At Cornell University Press, Michael McGandy had a ready answer for every question. His keen edits made for a more concise and more powerful book. Thanks as well to Mary Kate Murphy and others at the press.

My parents, Dave and Ginny Murphy, helped me in the writing of this book as they have throughout my life: generously, naturally, and invaluably.

To Kat, my wife, who made this book happen in a thousand ways: thank you, and I love you.

The book is dedicated to my children, Millie and Woody, in the faith that they will be both the builders and beneficiaries of a more just future.

CHAPTER 1

The African School

The mans name is lost, but his question reverberates.

Why, he asked, should his taxes go to support a school from which his children were excluded? It was January 1841. The unnamed man addressing the Rochester Board of Education was, of course, Black.

It could have been the farmer Solomon Dorsey or the barber Elijah Warr. It could have been Nelson or Richard Picket, two brothers and blacksmiths boarding together on High Street, or George Dixon, who waited tables at the Rochester House hotel. It could have been Samuel Brown or William Earl or Charles Thurell or any of the other dozens of common laborers crowded into the Black section of the Third Ward in flimsy, hastily built wood-frame houses, kindling waiting for a fire to come along and reduce them to ashes. It is no surprise that the petitioners name is lost; the surprise is that his question was recorded at all. It was one of only a handful of times in the citys first generation of public schooling that the input of Black families was noted. More often they were ignored and left to whatever teacher and whatever room could be obtained for the lowest price, if public money had to be dedicated at all. Better yet if they could be aided by the munificence of their friends.

When such munificence fell through, as it did more than once, the trustees did not upend their budget to replace it. That is why the unnamed man was at the meeting in the first place. Nine years after the trustees had first affirmed their responsibility to educate Rochesters few Black children, there existed no public school to receive them. The absence apparently had escaped notice, and the fathers petition left the school trustees red-faced. They referred it to a committee and the committee referred it to John Spencer, the state superintendent of common schools.

It is certainly desirable that this unfortunate class should have all the benefits of instruction, Spencer responded. The laws contemplate their instruction and provision must be made for it. But he elaborated: There must, however, be some discretion by the Trustees. Persons having infected diseasesidiotsinfants, incapable of receiving any benefit from the schooland persons over 21, who may be deemed too oldmay be excluded.... The admission of colored children is in many places so odious, that whites will not attend. In such cases the Trustees would be justified in excluding them, and furnishing them a separate room.

In the nineteenth century as in the centuries that followed, segregation in Rochester schools took a number of different forms. There was a time when Black children had essentially no access to public schools, followed by a period of explicit segregation written into local law, then a gradual unsanctioned spread of Black children into neighborhood schools. Throughout the period preceding the Black schools final closure in 1856, parents such as the unnamed Black father of 1841 had a difficult task in advocating for their children. Hardly any of the adults were themselves educated; many had escaped slavery or been emancipated. With few exceptions, the men worked as laborers and the women as servants in the homes of the white well-to-do. Black residents were outnumbered fifteen to one by white residents of the city and effectively unrepresented on the board of education. Still, the credit for desegregation is theirs. They petitioned and organized and, in the last resort, withheld their children from school rather than expose them to what they believed were unsafe conditions and prejudiced instruction. When the Black school closed in 1856, Rochester was the first city in New York with fully desegregated schools. Black families then did not know, of course, that the greater fight for desegregation would remain active more than 150 years later.