Contents

Guide

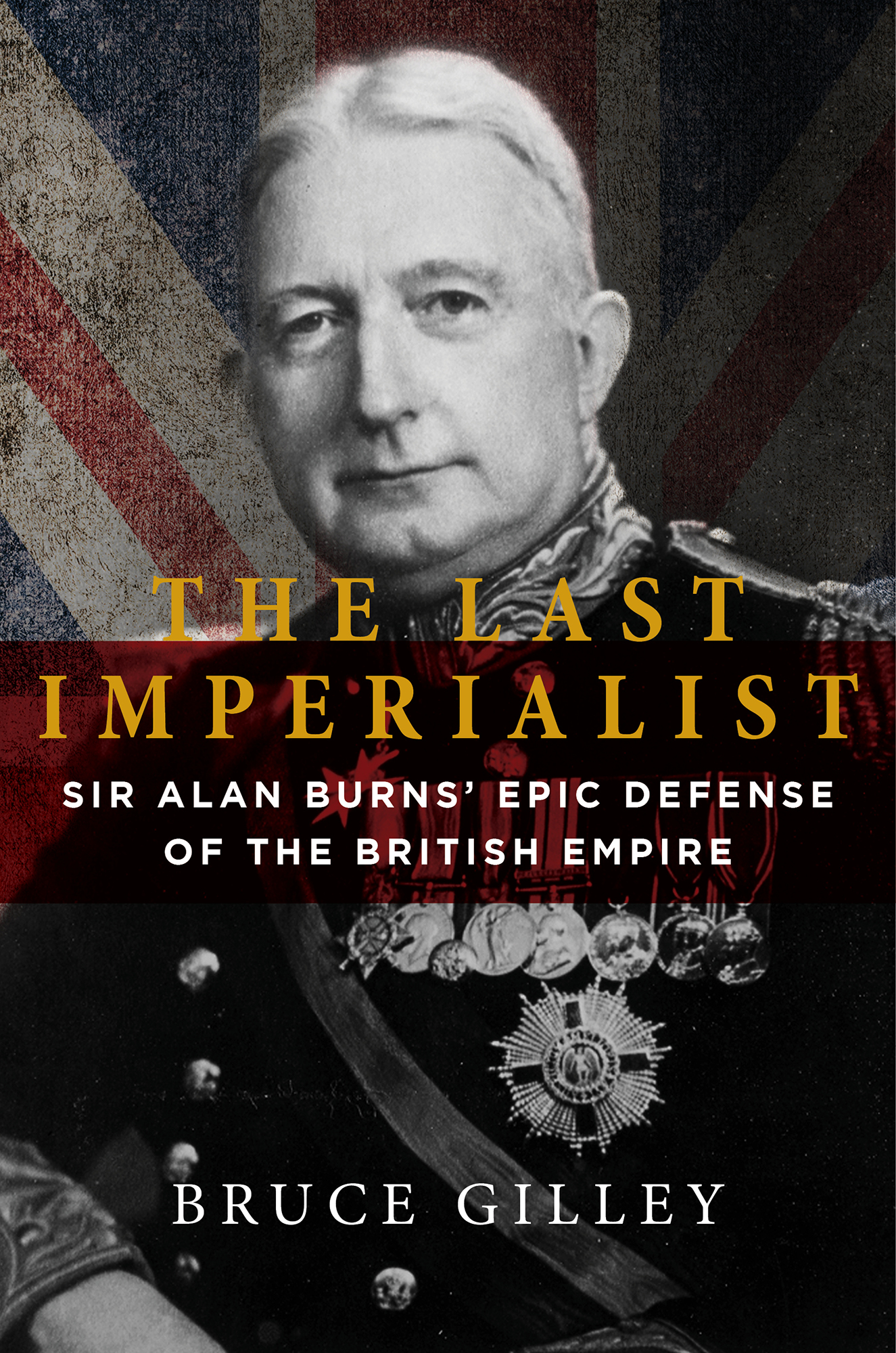

The Last Imperialist

Sir Alan Burns Epic Defense of The British Empire

Bruce Gilley

Copyright 2021 by Bruce Gilley

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, website, or broadcast.

Regnery Gateway is a trademark of Salem Communications Holding Corporation

Regnery is a registered trademark and its colophon is a trademark of Salem Communications Holding Corporation

Cataloging-in-Publication data on file with the Library of Congress

ISBN 978-1-68451-217-1

eISBN 978-1-68451-222-5

Published in the United States by

Regnery Gateway

An Imprint of Regnery Publishing

A Division of Salem Media Group

Washington, D.C.

www.Regnery.com

Books are available in quantity for promotional or premium use. For information on discounts and terms, please visit our website: www.Regnery.com.

Cover design by John Caruso

Dedicated to the family of Sir Alan Burns

For more information on The Last Imperialist, including photos, author interviews, and original documents, please visit the books website:

www.web.pdx.edu/~gilleyb/TheLastImperialist.html

List of Figures

Abbreviations Used in Notes

ACBSir Alan Cuthbert Maxwell BurnsAllenCharles Allen, Oral History Interview: Sir Alan Burns,

BBC Productions (1978), Imperial War Museum, Catalogue # 4708/03. Cassette numbers 1, 2, and 3.CBAASir Alan Burns,

Colonialism Before and After (unpublished, ca. 1973).CCCSir Alan Burns,

Colonial Civil Servant (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1949).CCT-GSir Alan Burns, Constitutional Changes in the Tropics, Talk at Centre for Industrial Studies, Geneva, October 20, 1953.C.O.Colonial Office.CO/Colonial Office archives, Public Records Office, London.CPSir Alan Burns,

Colour Prejudice, With Particular Reference to the Relationship Between Whites and Negroes (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1948).CPCW-GSir Alan Burns, Colour Prejudice in a Changing World, Talk at Centre for Industrial Studies, Geneva, October 21, 1953.CRP-GSir Alan Burns, Colour and Racial Prejudice, Talk at Centre for Industrial Studies, Geneva, October 29, 1951.DWPARichard Rathbone, Death and Politics: West Africa in the 1940s,

History Today (1993).FCO/Foreign and Commonwealth Office archives, Public Records Office, London.FO/Foreign Office archives, Public Records Office, London.FBCE-GSir Alan Burns, The Future of the British Colonial Empire, Talk at Centre for Industrial Studies, Geneva, February 1, 1950.HBWISir Alan Burns,

History of the British West Indies (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1954).HONSir Alan Burns,

History of Nigeria, 8th edition (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1972).HS/Special Operations Executive archives, Public Records Office, London.IDOCSir Alan Burns,

In Defence of Colonies: British Colonial Territories in International Affairs (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1957).KV/Security Service archives, Public Records Office, London.MCGCRichard Rathbone, A Murder in the Colonial Gold Coast: Law and Politics in the 1940s,

Journal of African History (1989).MPCGRichard Rathbone,

Murder and Politics in Colonial Ghana (1993).OPTSir Alan Burns, The Movement Towards Self-Government in British Colonial Territories,

Optima, June 1954.RCD-GSir Alan Burns, Recent Constitutional Developments in British Colonial Territories, Talk at Centre for Industrial Studies, Geneva, October 29, 1951.TCCC-GSir Alan Burns, The Colonial Civil Service, Talk at Center for Industrial Studies, Geneva, October 11, 1951.UN-GSir Alan Burns, The United Nations, Talk at Centre for Industrial Studies, Geneva, October 21, 1953.UN/Official records of the United Nations. Available at: https://digitallibrary.un.org.

Part I FOUNDATIONS

Chapter 1 The Fate of Lesser Persons

The man straightened up in the airport waiting room and lowered his newspaper. His face was contorted with a mixture of emotionsanger, fear, sadnessat what he had just read. His rumpled suit and outdated waistcoat strained under the pressure. Theyd killed Danquah.

Danquah had been Sir Alan Burns nemesis. Danquah stood for opportunism and politics, while Burns stood for justice and administration. Danquah claimed to have ended Burns career. A promised post as governor of exotic Malaya was withdrawn and replaced by a taxing, high-profile decade at the United Nationsall because of Danquah. The last time they met, at the ceremony for Ghanas independence in 1957, the animosity was palpable. There were no handshakes, despite encouragement from bystanders. Danquah, a leading Ghanaian nationalist, boasted of how much pain he had inflicted on Burns, a former colonial governor. Full of confidence, Danquah was a man of the future, while Burns was a man of the past. Danquah was surrounded by reporters. Burns was ignored and flew home to shudders about the whole colonial enterprise. Now, eight years later, Danquah was dead, devoured by the revolution he started. Ghana was in steep decline, and the lives of close friends were at risk.

Accra, Ghana, February 4, 1965, New York Times ServiceDr. Joseph B. Danquah, a leader in the struggle for Ghanaian independence who later broke bitterly with President Kwame Nkrumah, died in detention today, the Government announced. The official statement said that Dr. Danquah, who was 69 years old, had died of a heart attack. He had been imprisoned since Jan. 8, 1964, under Ghanas Preventive Detention Act. In the decades before the Gold Coast became independent from Britain and changed its name to Ghana, Dr. Danquah was the colonys unquestioned political leader. After independence, he led the opposition against Kwame Nkrumah under a government that tolerated opposition less and less.

It was the twilight days of European empire. As colonial judges, station masters, revenue collectors, regimental commanders, and district officers came home, a long shadow of global indifference had spread over the affairs of newly independent countries like Ghana. Under that shadow, stories like the death of Danquah were now common. No one really cared anymore. Unless, like Sir Alan Burns, they remembered.

In retrospect, it was surprising how long Danquah had survived. A witty and self-effacing lawyer, Joseph Danquah was the sort of person that colonial officials like Sir Alan Burns hoped would assume power in newly independent states. He was pushed aside in 1947 by the radical Nkrumah, who had been trained in London by Britains Communist Party and in the United States by black racialists. Nkrumah abandoned the lawyerly constitutionalism of his mentor in favor of violent street protest. In the election prior to independence, Nkrumahs party trounced the moderates represented by Danquah with promises of untold riches and freedom once the British left.

The moment the Union Jack was lowered, Nkrumah introduced a series of repressive measures and steered West Africas most prosperous economy into a wall. Eleven of the twelve opposition members in Parliament were soon in prison. By 1965, wages had fallen to levels not seen since the 1930s, while Ghanas foreign reserves, carefully built up under the British, had evaporated. Cocoa farmers, the backbone of the economy, were paid half the market price by Nkrumah. The British had paid them 50 percent above the market price. Backbenchers in the ruling party began to grumble that things were worse than in colonial days. Danquah wrote to Nkrumah about an anti-climax of repression after liberation.