Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To my parents, Pat and Olu Shonubi; my grandparents, Verna and Charles Robertson; and my daughter, Adedayo: You remind me that the wisdom of back home and the knowledge of our ancestors is at the foundation of my hope for the future.

Nathaniel Rich

W hat follows is the story of our time. One of the most incredible things about it is that very few people know how it began (though you will, soon), and nobody knows how it will end (though you, decades from now, might). The most surprising thing about it, however, is that you and I and everybody we know are its main characters. As you read this story, remember that you are also its hero.

The story of climate change, and our response to it, is the story of modern civilization. Consider all the godlike powers we take for granted: refrigeration; indoor cooking; temperature control; modern medicine; motorcycles, cars, buses, helicopters, airplanes, spaceships; the internet; supermarkets and everything you find in them; laundry machines, dishwashers, lightbulbs, garage doors, sneakers, books, plastic, TikTok. Nearly any technology that shapes our lives relies upon the consumption of massive quantities of energy. For nearly all of human history, most of that energy has come from burning fossils. Eons worth of dead thingsdinosaurs, trilobites, plants, trees, moss, algaedecomposed, sunk into the Earth, and were dug up and burned by enterprising human beings. Like something out of a zombie movie, however, the Earths dead things are now seeking their revenge, overheating the planet and sowing chaos. Our greatest source of power has yielded the most vicious threat our civilization has faced.

The story of climate change is also the story of human failure: of warnings ignored, of missed opportunities, and of malevolent actors, chief among them those who have profited from the extraction and manufacture of fossil fuels. As I write this introduction, in 2022, we are only beginning to rid ourselves of the disinformation campaign that was codified at the highest levels of the oil and gas industry in the late 1980s, just as major global climate policy was being proposed and drafted by the United States and the worlds other largest nations. The disinformation campaign persists, however, as does the political division it caused.

We have been brought to this point by the nearsighted decisions of powerful people in positions of great responsibility. Anyone born in the twenty-first century will, at some point in their lives, come to realize that they have been dealt a bad hand. Those who are most responsible for getting us into this mess are the ones who will be least harmed by it. The most innocentthe youngestwill suffer the most. The perverse cruelty of climate change cuts along every social divide. It aggravates nearly every form of inequality in society. Those who face the sharpest discriminationpeople of color, Indigenous communities, the poor, the infirm, the undereducatedare most severely threatened. Those who want most badly to defeat the problem often have the least political power to do so.

This grim history does not doom us to a grim future. A vast range of outcomes remains available, with an enormous gulf between best- and worst-case scenarios. And more than forty years after Rafe Pomerance, James Hansen, and Al Gore first tried to force the United States government to act, a new generation has seized leadership of the fight, with sudden, and dramatic, consequences.

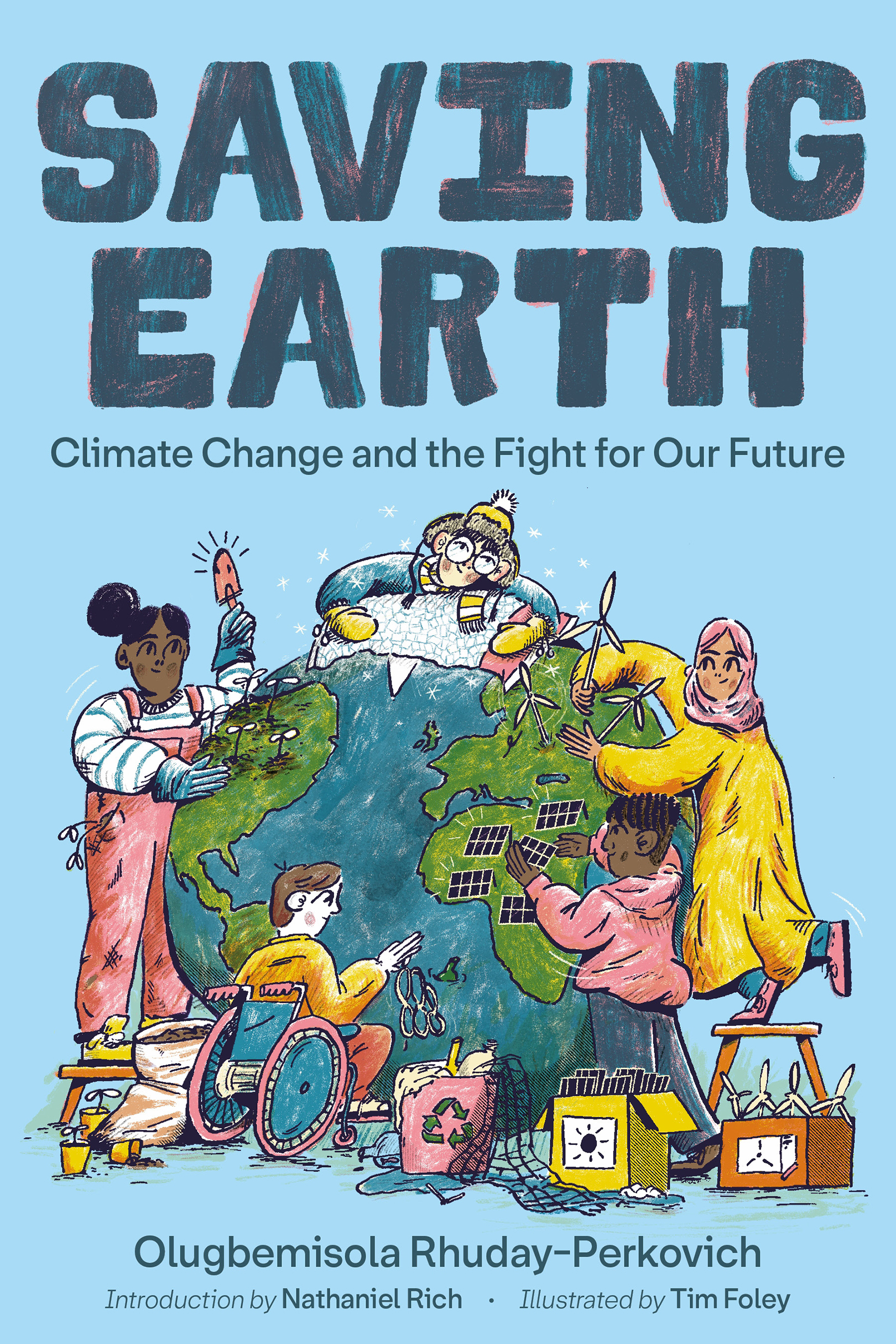

In Saving Earth, Olugbemisola Rhuday-Perkovich explains how we got here, gives a vivid portrait of the critical moment in which we find ourselves, and introduces the young visionaries who have reshaped the public conversation in just a few years. The future, we know, will look nothing like the past. It will be warmer, yes, and the strains of climate change will harm us in ways both darkly predictable and unforeseen. But the struggle against the ravages of warming will also be led by a new cohort of activists, engineers, and thinkers. This new generation doesnt look like the previous ones, and it wont act like them either. Young people faced with the threat of climate change in the 2020s will not tolerate delays or make excuses. They wont be distracted by the old political tricks. They will understand that survival of the world as we know it will depend on a profound commitment to honesty, responsibility, and, above all, justice.

Saving Earth is their storyand yours.

Today, almost nine out of ten Americans do not know that scientists agree, well beyond the threshold of consensus, that human beings have altered the global climate through the indiscriminate burning of fossil fuels.

Nathaniel Rich, Losing Earth: A Recent History

Vision, Voices, and Vegetables

I n 2009, New York City students at the Brooklyn New School started a campaign that later became part of an effort called Styrofoam Out of Schools. Their mission? Well, you can probably guess it from the name. But to be clear, they wanted to get plastic-foam lunch trays out of schools.

The students werent worried that the trays were too flimsy or ugly or made out of a weird substance that wasnt found in nature. They werent trying to be different, even though the idea of using anything other than plastic-foam trays in cafeterias was very different. They were concerned that the trays, which were used for only a few minutes before they were tossed in the trash, were not biodegradable and stayed around for hundreds, if not thousands, of years.

Styrofoam is the trade name for polystyrene foam, a plastic material with many tiny air pockets trapped in its structure. Like many plastics, polystyrene is derived from petroleum. Plastic foam is used in food containers, packaging, insulation, and more because it is lightweight, inexpensive to produce, and excellent at keeping hot things hot and cold things cold. But its also well, plastic, and not biodegradable. Thats just one of its problems. Not only is fossil fuel an ingredient, but the manufacturing process releases greenhouse gases that cause global warming (which can be said of the manufacturing process of just about any product), and it involves toxic chemicals linked to cancer. When the foam is heated, toxic chemicals can transfer from the plastic into the food and drink the containers were designed to protect. And finally, after the plastic foam has been used just once, it often ends up floating in waterways and oceans, where it breaks into tiny pieces that animals mistake for food, which can lead to their early death.

PETROLEUM: Another word for oil. A liquid that is naturally present in certain layers of rock beneath the Earths surface. It can be removed and refined to produce fuels including gasoline, kerosene, and diesel oil. Like coal, petroleum is a fossil fuel, meaning that it is formed over millions of years from the remains of plants and animals deep within the Earths crust.

At the time, over four million foam trays in New York City alone were being trashed every week, to be taken to landfills, where plastic foam can last for up to five hundred years, or burned in fiery incinerators, where it can produce harmful fumes. The disposable lunch trays didnt just disappear. They hung around, degrading into smaller and smaller pieces and potentially leaching toxic chemicals, polluting and poisoning our soil, water, marine lifeour very selves. Gross, right? And this was a normal part of everyday life.