Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

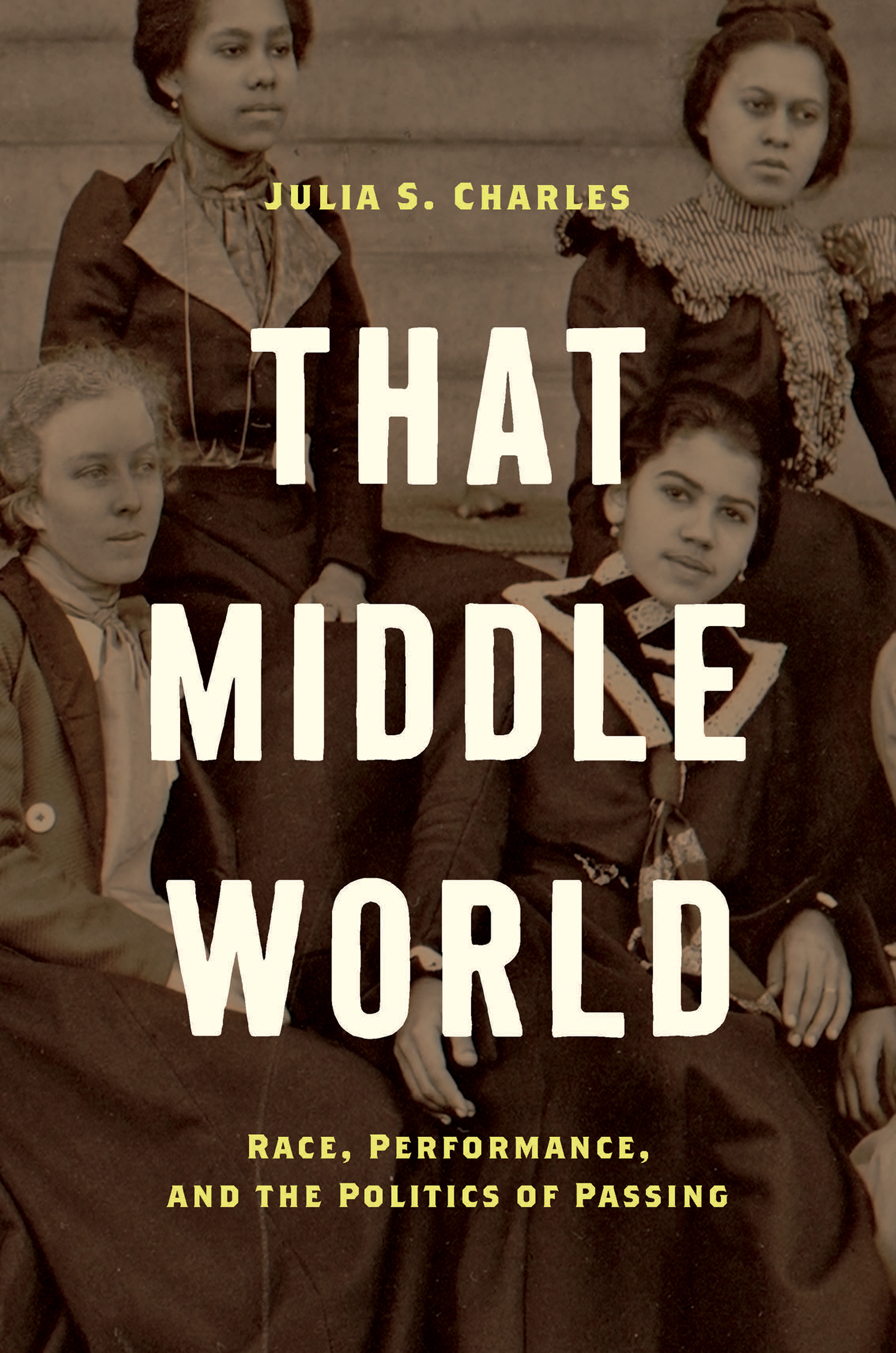

That Middle World

JULIA S. CHARLES

That Middle World

Race, Performance, and the Politics of Passing

The University of North Carolina Press Chapel Hill

2020 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Set in Arno Pro by Westchester Publishing Services

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Charles , Julia S., author.

Title: That middle world : race, performance, and the politics of passing / Julia S. Charles.

Description: Chapel Hill : The University of North Carolina Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019053157 | ISBN 9781469659565 (cloth) | ISBN 9781469659572 (paperback) | ISBN 9781469659589 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Passing (Identity) in literature. | Racially mixed people in literature. | Race in literature. | American literatureAfrican American authorsHistory and criticism. | Racially mixed people Race identityUnited States. | Race awarenessUnited States.

Classification: LCC PS169.P35 C48 2020 | DDC 810.9/352996073dc23

LC record available at https: / /lccn.loc.gov/2019053157

Cover illustration: Detail of Thomas E. Askew (18501914), Nine African American Women (Atlanta, Georgia, 1899). Courtesy of the W. E. B. Du Bois Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

For Ayanna, Julia, and Isaiah

Yet these stories, after all, are Mr. Chesnutts most important work, whether we consider them merely as realistic fiction, apart from the author, or as studies of that middle world of which he is naturally and voluntarily a citizen. We had known the nethermost world of the grotesque and comical negro and the terrible and tragic negro through the white observer on the outside, and the black character in its lyrical moods we had known from such an inside witness as Mr. Paul Dunbar; but it had remained for Mr. Chesnutt to acquaint us with those regions where the paler shades dwell as hopelessly, with relation to ourselves, as the blackest negro. He has not shown the dwellers there as very different from ourselves. They have within their own circles the same social ambitions and prejudices; they intrigue and truckle and crawl, and are snobs, like ourselves, both of the snobs that snub and the snobs that are snubbed. We may choose to think them droll in their parody of pure white society, but perhaps it would be wiser to recognize that they are like us because they are of our blood by more than half, or three quarters, or nine tenths. It is not, in such eases, their negro blood that characterizes them; but it is their negro blood that excludes them, and that will imaginably fortify them and exalt them. Bound in that sad solidarity from which there is no hope of entrance into polite white society for them, they may create a civilization of their own, which need not lack the highest quality. They need not be ashamed of the race from which they have sprung, and whose exile they share; for it may in many of the arts it has already shown, during a single generation of freedom, gifts which slavery apparently only obscured.

William Dean Howells

Contents

Figures

Acknowledgments

Often, it is not until the culmination of a thingin this case, a bookthat I stand still long enough to reflect on how it came to be. This processof theorizing, writing, questioning, doubting, revising, nearly quitting, reaffirming, and finally finishing That Middle Worldhas been quite a journey, sometimes delightful because of the ways in which thoughts begin to come together, sometimes disorienting because of the ways in which they dont. Throughout the many changes that have occurred in my life since the start of this bookgraduating, relocating, starting a new job, and all that comes with those transitionsThat Middle World has remained. It has been so present at times that it revealed itself in the most unexpected ways as part of everyday living; it has been so hidden at times that I wondered if it would ever show itself again through the fogginess. Yet whether visible or veiled, it has been a reassuring constant, revealing to me its merits. It has reminded me that the subjects I write about within these pages matter a great deal to the history of America and the shaping of American identity. Thus, nearly every day I came to this work with anticipation, anxiety, and, later, unwavering confidence that there was a thread here of the national fabric that had yet to be revealed in the way I believed it should be. And so I continued to write. The commitment to this work is rooted, as I hope all my work is, in humanity. It is the promise to bear allegiance, scholarly as it is, to the people and characters who have shown us who we are and helped redefine nationhood, especially those whose bodies bear the weight of a racially fraught nation. These stories have given me the freedom to ask tough questions, to search for answers, and, indeed, to dream about one day being in conversation with the many able passing literature scholars whose work prefigures my own, for whom I have deep respect, and in whose academic lineage I now fall.

What a journey this has been! The topsy-turvy ride that culminated in That Middle World: Race, Performance, and the Politics of Passing would never have started were it not for two women, tiny in stature yet looming large in personality, demand, and expectation: Drs. Esther M. A. Terry and Linda B. Brown. As the cofounder of the PhD program in Afro-American Studies at UMass and, perhaps more serendipitously, as a graduate of the English Department at Bennett Collegethe same department from which I graduatedDr. Terry has certainly left an indelible mark on my life and scholarship. I am overjoyed to have been supported, loved, and, when necessary, chided by her. And thank you to Dr. Brown, who is also a graduate of Bennett College and was my English professor there. Dr. Brown was my first sustained look at what this academic life could be. She was the first to offer me Black writers as something much more than an appendage to white American writers, and that has since sustained me. What began as a mandatory class at Bennett College in Greensboro, North Carolina, has become a passion for excavating the lives of Black folks like us and a staunch refusal to let our histories be narrated in anything other than unabashed truth and love. And that is certainly because of these two Black women. It is my sincerest hope that I have made them proud or, at least in some small measure, glad to have helped and encouraged me. Indeed, it takes a Belle.

A special thanks to the folks in the English Department at North Carolina A&T State University, especially to my cohorts, who have become good friends within and outside the academy. Aggie Pride! I am forever indebted to Bennett College herself, for without her, I would not have learned the responsibility of voice or the legacy of civic action. I remain true to thee, indeed.

In my five years as assistant professor of African American Literature in the English Department at Auburn University, I have had the support of many colleagues, some of whom have become great friends. I am deeply thankful for their support and kindness, especially for Paula Backscheider, Sunny Stalter-Pace, and Emily Friedman, who have made themselves available to answer my many questions. Mostly, though, I am eternally thankful to my colleague-turned-friend Susana Morris, who has held my hand as I learned what the professoriate is all about for a Black woman feminist. She has lent me her ear and, when necessary, her voice, and I owe her a great debt, which she would never ask me to repay.