Also by Ann Tusa

THE NUREMBERG TRIAL (with John Tusa)

THE BERLIN AIRLIFT (with John Tusa)

Copyright 1997 by Ann Tusa

Foreword Copyright by Raymond G.H. Seitz

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Rain Saukas

ISBN: 978-1-5107-4063-1

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-4064-8

Printed in the United States of America

Contents

Illustrations

Section I

Section II

Foreword to the 2018 Edition:

Berlin and the Wall

A ny basic library designed to recount the history of the Cold War would include perhaps a dozen essential books. Ann Tusas story of Berlin and its notorious wall would necessarily be one of them.

The Cold War was ideological and global. Hardly a country in the world was unaffected at one stage or another. For a half-century, the Communist camp, led by the Soviet Union and with an independent but complementary role played by China, and the Western camp, led by the United States at the center of a network of international alliances, challenged each other in a deadly game of geopolitical chess. Both sides engaged in proxy wars, subversion, propaganda, and espionage. Sometimes ingeniously, sometimes recklessly, each side probed the vulnerability or resolve of the other. And by the time the struggle had matured, both sides bristled with nuclear weapons and plotted the possibility of Armageddon.

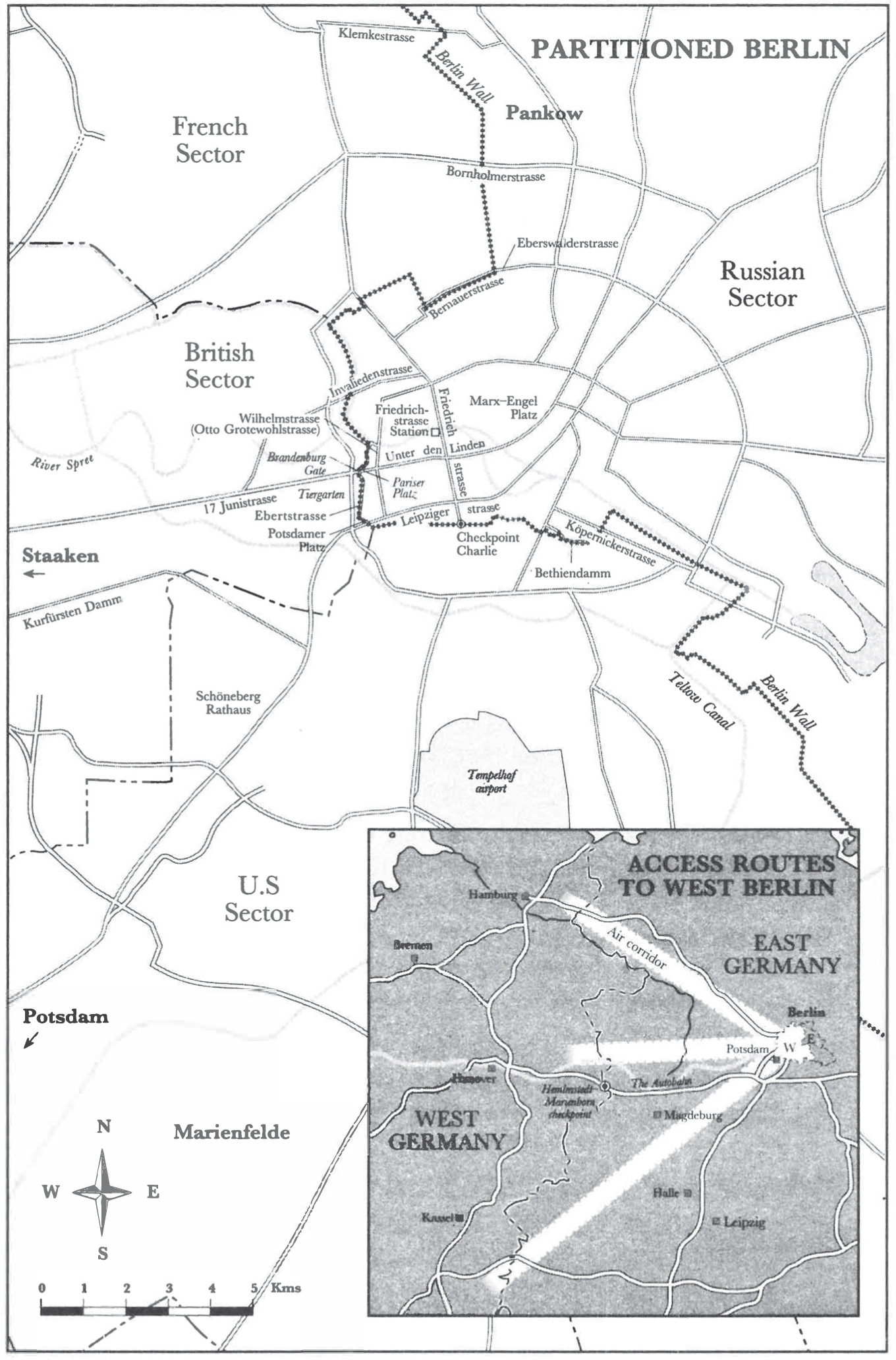

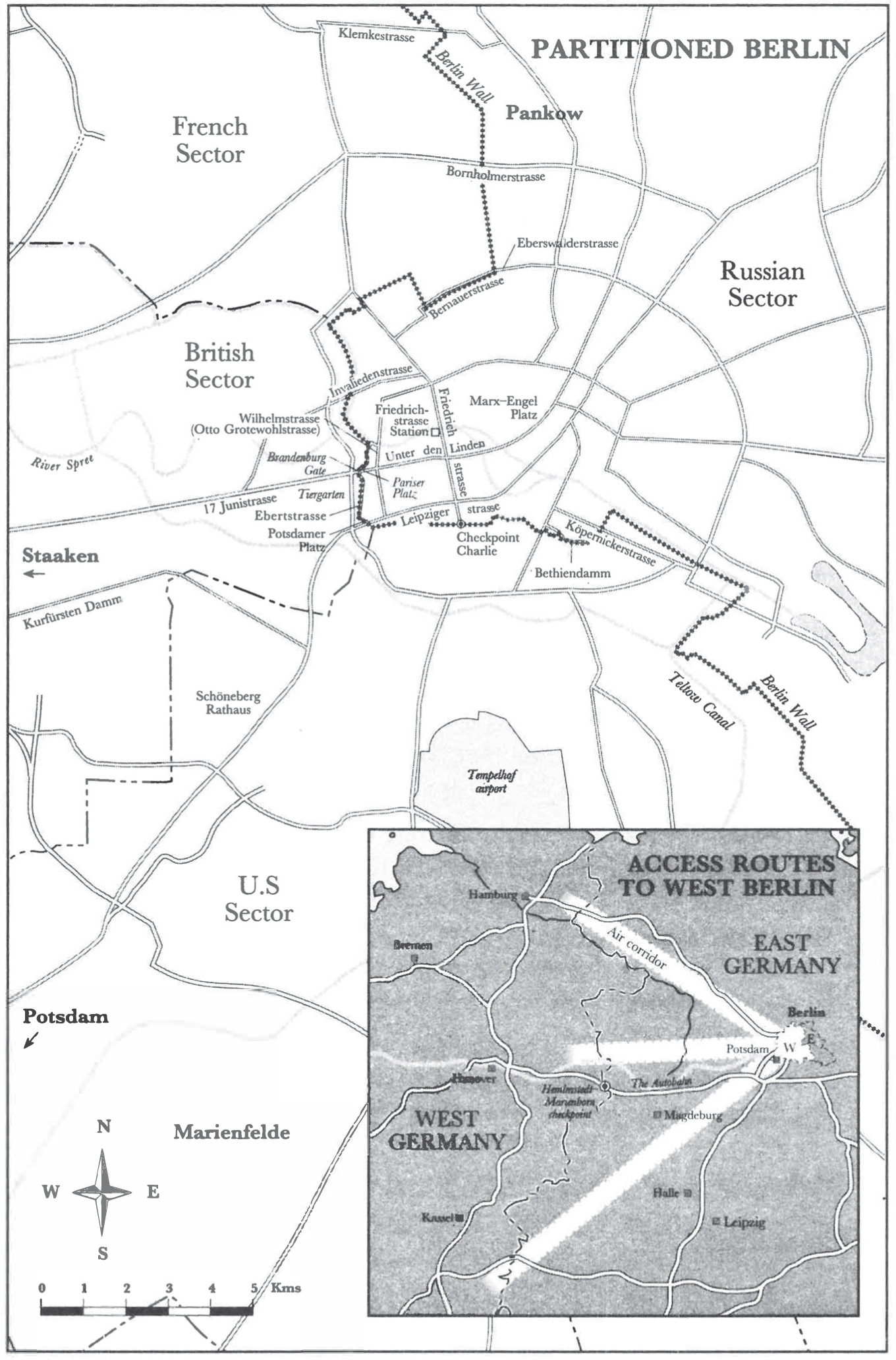

Nowhere was the confrontation more brittle, dangerous, and symbolic than in Berlin. Here the sides were toe-to-toe and nose-to-nose. At the end of the Second World War, the German capital (not much more than rubble at the time of surrender) was divided into four sectors, each to be administered by the occupying military authorities of the respective victorious powers: the United States, the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, and France. Though separated administratively, the victors shared rights in the city as a whole. But Berlin was an isolated island, set well within the Soviets much broader occupation zone of all of eastern Germany, and surrounded by 350,000 Soviet troops. The Western allies had sensibly negotiated defined access corridors, by land and air, in order to logistically support their tiny garrisons stationed in this encircled enclave.

The Western powers expected the arrangement to be temporary pending the rapid reconstruction and reunification of Germany. But the Soviets had no intention of giving up their conquered German territory or their dominant position in Berlin. So began Moscows efforts to throttle the Allied presence, frequently by intimidation and harassment of Allied rites of passage and once by blockade, which the West countered in a dramatic airlift to sustain Berliners.

Berlin thus became a local test of wills smack at the center of the global confrontation between East and West. The city was called a flashpoint, a tripwire, a vortex, a barometer, a fuseand it was all of these. The danger lay in the recognition that a minor incident or a miscalculated threat could quickly escalate into a full-blown military crisis, including the ultimate possibility, in theory at least, of a cataclysmic nuclear exchange.

The Soviet squeeze play failed. Whenever pushed, the Alliesunited but not always harmoniouspushed back. But what really undid the Soviet plan were the Berliners themselves. West Berlin proceeded on its unilateral course of recovery and development, emerging prosperous, free-spirited, and defiant, while East Berlin sank into a grim, gray police state. The contrast was stark. No surprise, then, that East Berliners started to emigrate in droves to the West side of the city, especially the skilled workers. By the early 1960s, the flow had become a haemorrhage that threatened to destabilize the entire East German economy.

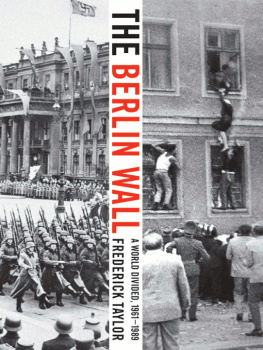

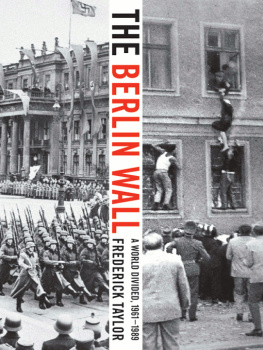

In August 1961, the Wall went up. At first it was only a barbed wire barrier, but this was quickly followed by a double wall of concrete, a no-mans kill zone, police patrols, dogs, checkpoints, and watchtowers. It was the first border wall in history, it was said, designed to keep people in rather than out. The Wall meant that the division of the city was permanent and that the status quo was fixed. Berlin seemed destined to become a political fly in Cold War amber. The Wall not only split the city but also symbolized the separation of the two Germanys, the division of all of Europe, and the global divide between tyranny and freedom.

But in November of 1989, the Wall collapsed, both physically and psychologically, in an outburst of jubilation. Over the long Cold War stalemate, the Western powers had held firm in Berlin; but again, it was the Berliners who forced the denouement. The emigration resumed, this time going around the Wall via the more open societies in Czechoslovakia and Hungary. When Mikhail Gorbachev told the East German government that it was on its own and should not expect Soviet intervention, the jig was up. East Berlins rotten regime disintegrated, and in the days that followed, so did the Wall.

The debris of the Wall paved the way to German unification and the end of communist government in all of Eastern Europe. It also opened up the prospect of a Europe whole and free and at peace. Things havent quite worked out that way, but the vision remains valid. Determined leadership and firm resolve may yet produce the reality.

This complex, tangled story is told by Ann Tusa with superb clarity. She enlivens grand events with the color of anecdote and detail. Spiced with wry humor, Tusa captures the cast of characters in her fine pen portraits: the mercurial, bullying Khrushchev; the tepid, compromising MacMillan; the nave but quick-read Kennedy; the haughty, steadfast deGaulle; the irascible, wily Adenauer, and many others. Above all, she illuminates exactly what was at stake in the beleaguered, combustible, noble city of Berlin: the durability and resilience of Western values.

Next page