ENCOUNTER BROADSIDES: a new series of critical pamphlets from Encounter Books. Uniting an 18th-century sense of political urgency and rhetorical wit (think The Federalist Papers, Common Sense) with 21st-century technology and channels of distribution, Encounter Broadsides offer indispensable ammunition for intelligent debate on the critical issues of our time. Written with passion by some of our most authoritative authors, Encounter Broadsides make the case for liberty and the institutions of democratic capitalism at a time when they are under siege from the resurgence of collectivist sentiment. Read them in a sitting and come away knowing the best we can hope for and the worst we must fear.

T HERE is little dispute that the Internet should continue as an open platform, notes the U.S. Federal Communications Commission. Yet in a curious twist of logic, the agency has moved to discontinue the legal regime yielding that open platform. In late 2010, it imposed network neutrality regulations on broadband-access providers, both wired and wireless. Networks cannot block subscribers use of certain devices, applications, or services, or unreasonably discriminate, offering superior access for some services over others. The commission argues that such rules are necessary, as the Internet was designed to bar gatekeepers. The view is faulty, both in its engineering claims and its economic conclusions. Networks routinely manage traffic and often bundle content with data transport precisely because such coordination produces superior service. Universities, for example, bar peer-to-peer services such as Skype; these nonprofit institutions harbor no hidden agendas and limit traffic simply to improve network performance for users. When walled gardens emerged at AOL in 1995, with Japans DoCoMo i-mode in 1999, or with Apples iPhone in 2007, they often succeeded in disrupting old business models attracting subscribers and providing golden opportunities for application developers. In many cases, these gardens have dropped their walls; others remain lush. This platform rivalry advances innovation and growth. A truly open Internet allows consumers, investors, and entrepreneurs to choose among many models, discovering efficiencies. The FCC mistakes the benefits of market processes for a planned industrial structure, imposing new rules to protect what evolved without it.

I. T HE N EW N ETWORK N EUTRALITY R ULES

The U.S. Federal Communications Commission, seeing the Internet as a fragile ecosystem under threat from opportunistic broadband providers, issued its

On Jan. 10, 2011, the FCC received its first official complaint not against a gigantic corporation but an upstart wireless competitor providing innovative services, advanced technologies, and new options for low-income consumers.

The targeting of socially valuable entrepreneurship is hardly an accident. The regulatory effort preserving the free and open Internet, as the FCC frames it mistakes the benefits of market rivalry for an architectural design. Competitive forces have driven firms to create vast data networks, continually upgrading their scope, speed, and quality. Cooperative agreements among these systems permit traffic to flow seamlessly through myriad gateways across the U.S. and around the world. Customers flock to these networks, eager to access a wondrous world of websites and online services, a thriving digital bazaar. This bountiful marketplace has emerged unplanned, unregulated, from the visions of technologists, the risks of venture capitalists, and the innovations of entrepreneurs, large and small.

The FCC mistakes the benefits of market processes for a planned industrial structure, imposing new rules to protect what evolved without it.

But that may change. Net neutrality (NN ) rules restrict how companies may price and package computer network services. The rules prohibit bargains or bundles that are seen to discriminate among applications. Regulators see danger lurking in your broadband ISP , the cable TV system putting you online via a cable modem, or the telephone carrier connecting you via a digital subscriber line (DSL ) or fiber-to-the-home (FTTH ) networks. The operator, left to its own devices, is feared to maximize profits not just by taking your monthly subscription fee but by then skimming an unearned surcharge.

By covertly blocking or degrading Internet traffic

Under the NN regime, rules generally mandate that ISPS not block access to (legal) websites or discriminate in the way traffic flows. Customers make all the choices on a platform that treats all applications alike. Subscribers pay their ISP only once, and content providers do not pay that ISP at all. Conduits are open. The network is neutral. Whats not to like?

II. C OMPETITION D ESTROYS THE I NTERNET . NOT.

On Jan. 10, 2011, we found out. MetroPCS, the fifth-largest mobile network that competes with larger carriers by offering discount prices and short-term contracts, must defend itself. While its $40 a month all you can eat voice, text, and data plan does not accommodate video streaming or certain peer-to-peer applications, MetroPCS slipped in a bonus: free, unlimited YouTube videos.

Organizations favoring NN went ballistic. A referencing MetroPCS.

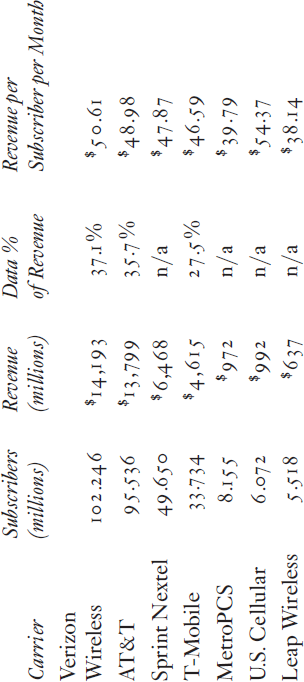

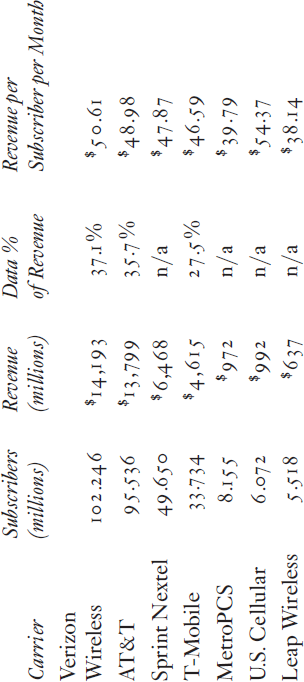

The complaint performs a great public service, revealing just how the commissions new regulations would adequately protect mobile broadband users. In fact, MetroPCS possesses no market power. With 8 million customers, it is the countrys fifth-largest mobile operator, less than one-tenth the size of Verizon. (See .) Under no theory could it force customers to patronize certain websites. It couldnt extract monopoly cash if it tried to.

Low-cost, prepaid plans offered by MetroPCS are popular with price-sensitive customers and, particularly, with cord cutters whose only phone is wireless. Usage is intense. Voice minutes per month average about 2,000, more than double those of larger carriers. That implies that the average customer on the $40-per-month unlimited calling plan is paying just 2 cents per minute of use, half the U.S. average (which is itself the lowest among all developed economies). And unlimited texting, e-mail, and Web browsing are tossed in for free.

TABLE I.

TOP U.S. WIRELESS CARRIER METRICS, Q4 2010

The $40 plan is inexpensively delivered via 2 G (second-generation) technology. It is not technically broadband and has software and capacity issues. In general, voice-over-Internet protocol (VoIP) is not supported by handsets, and video streaming is not available on the network. The carrier deals with those limitations in three ways.

First, the $40-per-month price tag extends a fat discount. Unlimited everything can cost $120 on faster networks. Second, at a cost of a few billion dollars, it has deployed new 4G technology, offering both a $40 tier similar to the 2G product (no video streaming) but also a pumped-up version with video streaming, voice calls over Internet (via Skype), and everything else for $60 a month.

Next page