Margaret MacMillan - Nixon and Mao: The Week That Changed the World

Here you can read online Margaret MacMillan - Nixon and Mao: The Week That Changed the World full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2007, publisher: Random House, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Nixon and Mao: The Week That Changed the World

- Author:

- Publisher:Random House

- Genre:

- Year:2007

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Nixon and Mao: The Week That Changed the World: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Nixon and Mao: The Week That Changed the World" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

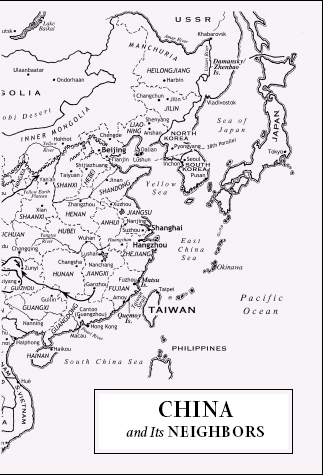

That monumental meeting in 1972during what Nixon called the week that changed the worldcould have been brought about only by powerful leaders: Nixon himself, a great strategist and a flawed human being, and Mao, willful and ruthless. They were assisted by two brilliant and complex statesmen, Henry Kissinger and Chou En-lai. Surrounding them were fascinating people with unusual roles to play, including the enormously disciplined and unhappy Pat Nixon and a small-time Shanghai actress turned monstrous empress, Jiang Qing. And behind all of them lay the complex history of two countries, two great and equally confident civilizations: China, ancient and contemptuous yet fearful of barbarians beyond the Middle Kingdom, and the United States, forward-looking and confident, seeing itself as the beacon for the world.

Nixon thought China could help him get out of Vietnam. Mao needed American technology and expertise to repair the damage of the Cultural Revolution. Both men wanted an ally against an aggressive Soviet Union. Did they get what they wanted? Did Mao betray his own revolutionary ideals? How did the people of China react to this apparent change in attitude toward the imperialist Americans? Did Nixon make a mistake in coming to China as a supplicant? And what has been the impact of the visit on the United States ever since?

Weaving together fascinating anecdotes and insights, an understanding of Chinese and American history, and the momentous events of an extraordinary time, this brilliantly written book looks at one of the transformative moments of the twentieth century and casts new light on a key relationship for the world of the twenty-first century.

Margaret MacMillan is the author of Women of the Raj and Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World, which won the Duff Cooper Prize, the Samuel Johnson Prize for Non-Fiction, the Hessell-Tiltman Prize for History, a Silver Medal for the Arthur Ross Book Award of the Council on Foreign Relations, and the Governor Generals Literary Award for nonfiction. It was selected by the editors of The New York Times as one of the best books of 2002. Currently the provost of Trinity College and a professor of history at the University of Toronto, MacMillan takes up the position of warden of St. Antonys College, Oxford, in July 2007. She is an officer of the Order of Canada, a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, and a senior fellow of Massey College at the University of Toronto

Margaret MacMillan: author's other books

Who wrote Nixon and Mao: The Week That Changed the World? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.