Compilation and annotation 2014 by Douglas Brinkley and Luke A. Nichter

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhco.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

The Nixon tapes / edited and annotated by Douglas Brinkley and Luke A. Nichter.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-544-27415-0 (hardcover)

1. Nixon, Richard M. (Richard Milhous), 19131994Political and social views. 2. Nixon, Richard M. (Richard Milhous), 19131994Archives. 3. United StatesPolitics and government19691974Sources. 4. United StatesForeign relations19691974Sources. 5. PresidentsUnited StatesArchives. 6. Audiotapes. I. Brinkley, Douglas. II. Nichter, Luke.

E856.N59 2014

973.924092dc23

2014011209

e ISBN 978-0-544-27737-3

v1.0714

To our wives, Anne Brinkley and Jennifer Nichter, and the townspeople of Perrysburg, Ohio

Introduction

Four decades later, we have all but forgotten that in late 1972 President Richard M. Nixon was at a political high point. That year, he made historic peace overtures with Americas Cold War enemies, first with China, then with the Soviet Union. The Vietnam War, which had long divided the American public, seemed to be drawing to a close. Nixon walloped Democratic rival George McGovern in his November reelection bid, 520 electoral votes to 17, capturing 61 percent of the popular vote. In recent memory, such levels of approval had been achieved only by Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1936 and Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964. Even though questions about Watergate hung in the air, the scandal never emerged as a major issue during the 1972 campaign. As Nixon hoped, the break-in remained a story of interest mainly inside the Washington Beltwayit would explode only in 1973.

On December 14, relaxing in the Oval Office, Nixon discussed his legacy, as it promised to develop at that point. He tried out ideas with White House Chief of Staff H. R. Bob Haldeman:

HALDEMAN: There are a lot of good stories from the first term.

NIXON: A book should be written, called 1972.

HALDEMAN: Yeah.

NIXON: That would be a helluva good book.... You get in China, you get in Russia, you get in May 8 [his dramatic decision to bomb and mine Hanoi and Haiphong just before his summit in Moscow], and you get in the election. And its a helluva damn year. Thats what I would write as a book. 1972, period.

By and large, that is the subject of this book: the public policy that drove the most significant year of the thirty-seventh presidents first term. The events of that hell of a damn year are presented just as they were recorded on Nixons taping system, uncensored and unfiltered.

Richard Nixons legacy is inseparable from his tapes, but White House taping started much earlier. In 1940, Franklin Roosevelt ordered that the thick wooden Oval Office floor be drilled to install wiring that would be used to record his press conferences. Harry Truman inherited FDRs system, adding a microphone to a lampshade on his desk. Dwight Eisenhower installed a new system that included a bugged telephone in the Oval Office. John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson used recorders provided by the U.S. Army Signal Corps that were capable of capturing hundreds of hours.

Despite the fact that other presidents also recorded, today it is Nixon who is known for bugging the White House. As far as we know, no president since Nixon has taped the way he did. He recorded more than all the rest combined, approximately 3,700 hours. At first, he had no plans to tape anything. Shortly after he was inaugurated on January 20, 1969, he ordered the dismantling of Lyndon Johnsons recording system. A bit of a klutz, he did not want the headache of dealing with electronics. Johnsons system required someone to monitor it and to turn it on and off each day.

Two years later, he changed his mind. Halfway into his first term, Nixon mused that none of his predecessors had employed sound-activated devices to capture everything. He wanted to be the first. Nixon presumed that his White House tapes would be an invaluable source for his memoirs. He believed, however, that in order to create an accurate record of his presidency, he should record everything, without discretion. What Kennedy didtaping moments of crisis like his ExComm meetings during the Cuban Missile Crisisstruck him as window-dressing history. I thought that recording only selected conversations would completely undercut the purpose of having the taping system, Nixon said. If our tapes were going to be an objective record of my presidency, they could not have such an obviously self-serving bias. I did not want to have to calculate whom or what or when I would tape.

Tapes of his meetings, he believed, would help set his administrations record straight and allow him to maintain the upper hand on history. The whole purpose, basically, Nixon told Haldeman during the first recorded conversation, is that there may be a day when... we want to put out something thats positive, maybe we need something just to be sure that we can correct the record.

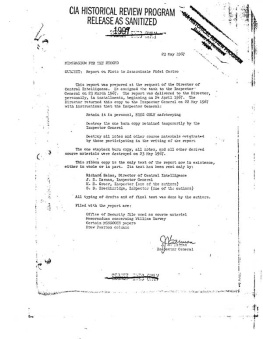

On Nixons instructions, the Technical Services Division of the U.S. Secret Service planted mini microphones throughout the Oval Office in February 1971. Five were concealed in the presidents desk, and two others were installed around the fireplace. Telephone lines in the Oval Office and the Lincoln Sitting Room were also recorded. Two more microphones were placed in the Cabinet Room. A central mixer, housed in a decrepit locker room in the White House basement, was the switchboard that coordinated the recording machines, Sony TC-800B open-reel models. Very few people knew about the taping system besides Nixon, Haldeman, Alexander Butterfield (who was responsible for its operation), and members of the Secret Service.

Soon after the systems initiation, Nixon liked it enough that he expanded its reach. The fact that everything he said was being saved appealed to his narcissistic sense of grandeur. He believed himself a world leader of great geopolitical insight and military strategy, like Churchill. Indeed, as this books sampling suggests, he was obsessed with foreign policy with suprisingly little interest in domestic issues. Fewer than 10 percent of the available tapes touch on domestic policy, and sadly, most of those conversations were in the Cabinet Room, where crosstalk and poor microphone placement rendered them among the most difficult to transcribe.

In April 1971, Nixon had four hidden microphones installed in his hideaway in the Executive Office Building, a private office in Room 180 where he could work away from the ceremony of the Oval Office. A year later, Aspen Lodge at Camp David was similarly outfitted, both the interior of the cabin and the telephone that Nixon used frequently when there.

The taping system gave Nixon an accurate record of his meetings and phone calls without the need for someone to sit in and take notes, which had been the practice before taping. It was simple. Nixon wore a pagerlike device provided by the Secret Service, and when it was within range of one of the taping locations, recording started automatically. There was no on or off switch. On some days we have recordings of almost his entire day as he moved between locations for different meetings or events. While not all are decipherable due to intermittently poor audio quality, the Nixon tapes represent a trove for historians unlike any record left by other presidents during the nations history. To fully transcribe Nixons tapes would take perhaps 150,000 pages, a task that may never be completed.

The vast majority of people recorded on the Nixon taping system did not know they were being recorded. The existence of the taping system was disclosed on July 16, 1973, by Alexander Butterfield during testimony before the Senate Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities, as part of the Watergate investigation. Mr. Butterfield, are you aware of the installation of any listening devices in the Oval Office of the president? Republican counsel Fred Thompson asked. It was an unexpected question. Under oath, Butterfield had no choice but to answer honestly. I was aware of listening devices. Yes, sir, he answered. The testimony changed the course of the Nixon presidency and American history. As Senator Howard Baker said, the purpose of the Senate investigation into the June 17, 1972, Watergate break-in and subsequent White House cover-up was to find out what the president knew and when he knew it. The tapes provided a way to answer those questions accurately, but they needed to be intact. On the reel for June 20, 1972, the recording was erased at a crucial point, an action for which Nixons secretary, Rose Mary Woods, largely took responsibility.

Next page