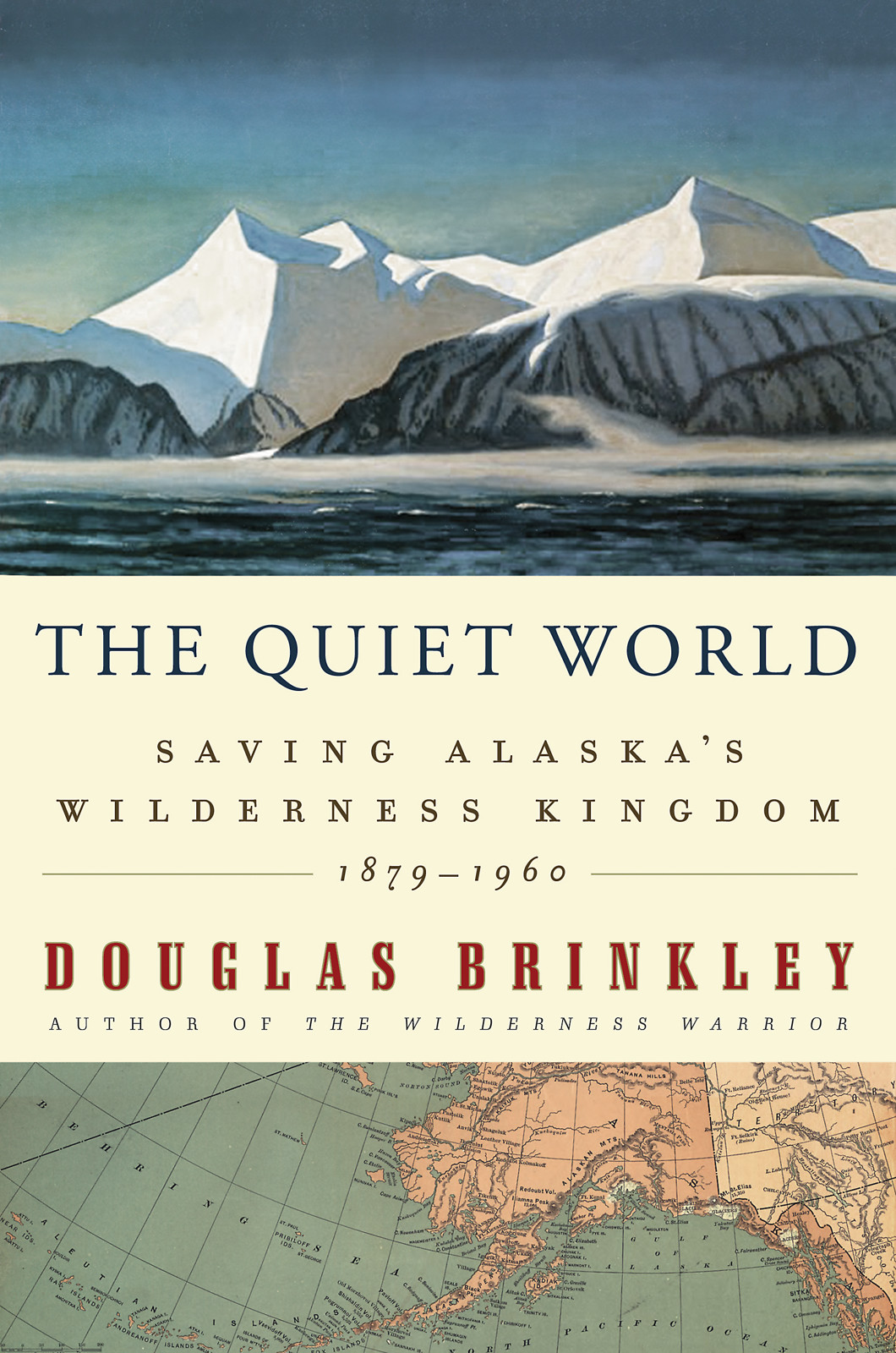

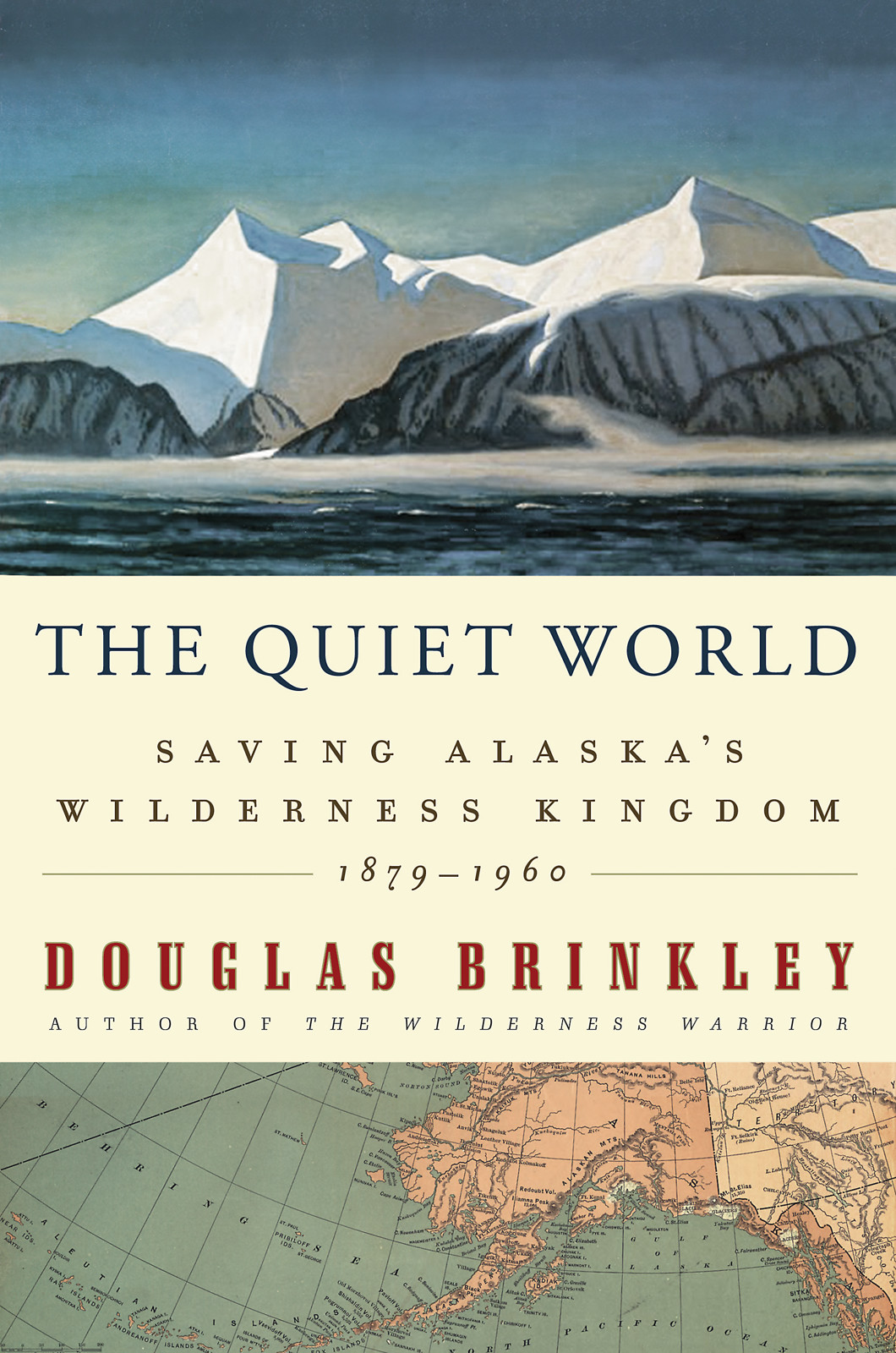

The Quiet World

......

SAVING ALASKAS WILDERNESS KINGDOM, 18791960

......

DOUGLAS BRINKLEY

To

SAM HAMILTON

Visionary at U.S. Fish and Wildlife... stout friend of Alaskas Arctic Refuge... and a true believer in the Quiet World.

&

STONE WEEKS

My twenty-three-year-old assistant at Rice University... killed in a trucking accident in Virginia on July 23, 2009.... He was an angel of pure future... with an intense love of wild Alaska.

&

EDWARD A. BRINKLEY

My father... who served in the U.S. Army as a sergeant with the 196th Regimental Combat Team during the Korean War from 1950 to 1952, based out of Fort Richardson, Alaska.... For telling me many great army stories about encountering grizzlies on his Alaska Range ski patrols from Haines to Fairbanks.

And I brought you into a plentiful country, to eat the fruit thereof and the goodness thereof; but when ye entered, ye defiled my land, and made mine heritage an abomination.

Jeremiah 1:6

When roads supplant trails, the precious, unique values of Gods wilderness disappear.

William O. Douglas , My Wilderness: The Pacific West (1960)

Is it not likely that when the country was new and men were often alone in the fields and the forest they got a sense of bigness outside themselves that has now in some way been lost.... Mystery whispered in the grass, playing in the branches of trees overhead, was caught up and blown across the American line in clouds of dust at evening on the prairies.... I am old enough to remember tales that strengthen my belief in a deep semi-religious influence that was formally at work among our people. The flavor of it hangs over the best work of Mark Twain.... I can remember old fellows in my hometown speaking feelingly of an evening spent on the big empty plains. It had taken the shrillness out of them. They had learned the trick of quiet.

Sherwood Anderson, letter to Waldo Frank (November 1917)

Contents

Glaciers move in tides. So do mountains. So do all things.

JOHN MUIR

I

H ow sad John Muir, founder of the Sierra Club, would be to learn that in the first decades of the twenty-first century many of the great glaciers of Alaska were melting away at an astonishing rate. Like the Creator himself, glaciers were architects of Earth, sculpturing vast ridges, changing bays, digging out troughs, making concavities in bedrock, and creating fast-flowing rivers.

John Muirthe naturalist whom Ralph Waldo Emerson called more wonderful than Thoreauhad erected a tiny observation cabin near a thirty-mile-long glacier that was one of Alaskas stunning heirlooms.

Despite all of Muirs cross-country tramps, nothing prepared him for the sheer poetic depth of the Alaskan wilderness. Muir considered himself a student of Louis Agassiz, an internationally celebrated Harvard zoologist and geologist, whose tudes sur les glaciers (1840) was the definitive word on glaciers in the 1870s. Agassiz had explored live glaciers, studying their origins in the Piedmont and Tidewater regions. Glaciers could be snow-white like typing paper or a brazen virtual blue, as gray as a gravel pit or as clear as H 2 O. Some extended over twenty square miles and could be as smooth as velvet or as wrinkled as a bull walruss neck. They had blotches, slashes, stripes, and swirls. Other cirque glacier remnants covered less than a square mile. When calving, a glacier rumbled and roared, then as the ice sank or floated a strange vibration, like wind chimes, curled the air as if a tuning fork had been bonked. Unbeknownst to most Americans of the late nineteenth century, glaciers constituted the biggest freshwater reservoir on Earth.

Muir was frustrated that in Yosemite he could analyze only the effects glaciers had on mountains; it was all the geological past. For his professional glaciology career to advance, he needed to see the real dealto experience glaciers themselves, in raw action. Alaska was, to Muir, the ideal laboratory for studying frozen motion as it flowed downhill as if icy blue lava. All glaciers were cold, solid, scalloped, and slippery. But besides those four basic features, each glacier had a distinct personality of its own. Muir, with the keen eye of a farmer inspecting his crops, was looking for fresh scientific evidence of glacial deformation, recession, and retreat. Every nuance mattered. Keys to Earths geological history could possibly be found by studying ice fields. Alaskas umpteen glaciers were to become his field teachers. When a portion of a berg breaks off, another line is formed, and the old one, sharply cut, may be seen rising at all angles, giving it a marked character, Muir reported. Many of the oldest bergs are beautifully ridged by the melting out of narrow furrows strictly parallel throughout the mass, revealing the bedded structure of the ice, acquired perhaps centuries ago, on the mountain snow fountains.

Muir, Americas legendary naturalist, first traveled to southeast Alaskas Inside Passage from June 1879 to January 1880.

Muirs journey began aboard the Dakota , which steamed out of San Francisco near Alcatraz Island and two days later churned past the high cliffs and tree-lined shores of Puget Sound, and then entered the waters of British Columbia. The Inside Passage, through which Muir was traveling, included all the waterways from north of Puget Sound to west of Glacier Bay. Next the Dakota threaded through the Alexander Archipelago islands to Sitka, Alaska. The ship, though occasionally protected by land, was terribly vulnerable to the Pacific gales. To the lean, bearded Muir, however, these 10,000 miles of southeastern Alaskan islands and fjords (long, deep arms of the ocean, carved out by a glacier) and 1,000 camelback islands, dense with western hemlock and Sitka spruce, were overabundantly beautiful for description. Giant cliffs billowed straight out of the seawater, rising 500, 600, 700 feet over the Pacific Ocean. A frustrated Muir kept pleading with the captain to stop and let him quickly climb a mountain, but to no avail.

As the Dakota ventured farther up the Inside Passage (now the longest protected marine waterway in the world), Muira taut man of forty, with red-brown hair and beard, always stooping over to jot notesplayed the populist professor. He kindly explained to tourists aboard that the snouts of glaciers shed blocks of ice in a calving process. With his thick Scottish brogue, Muir, a natural raconteur, made even the most citified tourist ready to paddle into quiet coves around Baranof Island, to kayak down a cleaved river as it roared out into Sitka Sound and then out to the Pacific. So excited had Muir become by the breathtaking scenery that he fantasized about climbing mountains up to Alaska from California someday, exploring Mount Shasta, Mount Hood, and Mount Rainier. What made Muir so special, the quality in his character that had made Emerson take note, was the way the enthusiastic naturalist fully integrated scientific knowledge with romantic wildness. Nobody could resist Muirs charm.

That fall of 1879 Muir furiously scribbled astute observations about Native Alaskan people, gold seekers, lumberjacks, canneries, and cosmic natural features. Muir even developed his own glacial gospel: that fjords and wilderness, like gentle magic, lifted the soul on a journey of self-discovery filled with an infinity of unknowns. Inner peace could be found in glaciers. Southeastern Alaska was an immortal land that would, in turn, immortalize him.

It took Muir only a day to become a booster for Alaskas magnificent Glacier Bay. The land uplift rate1 inch per yearwas among the highest in the world, because the glaciers receded, thus removing their considerable weight from the land. In his wilderness journalism Muir urged Americans to journey to paradisiacal Alaska and let their jaws drop. Although Muir didnt discover Glacier Bay, his enthusiasm made the bay internationally celebrated. Go, Muir cried, go and see.

Next page