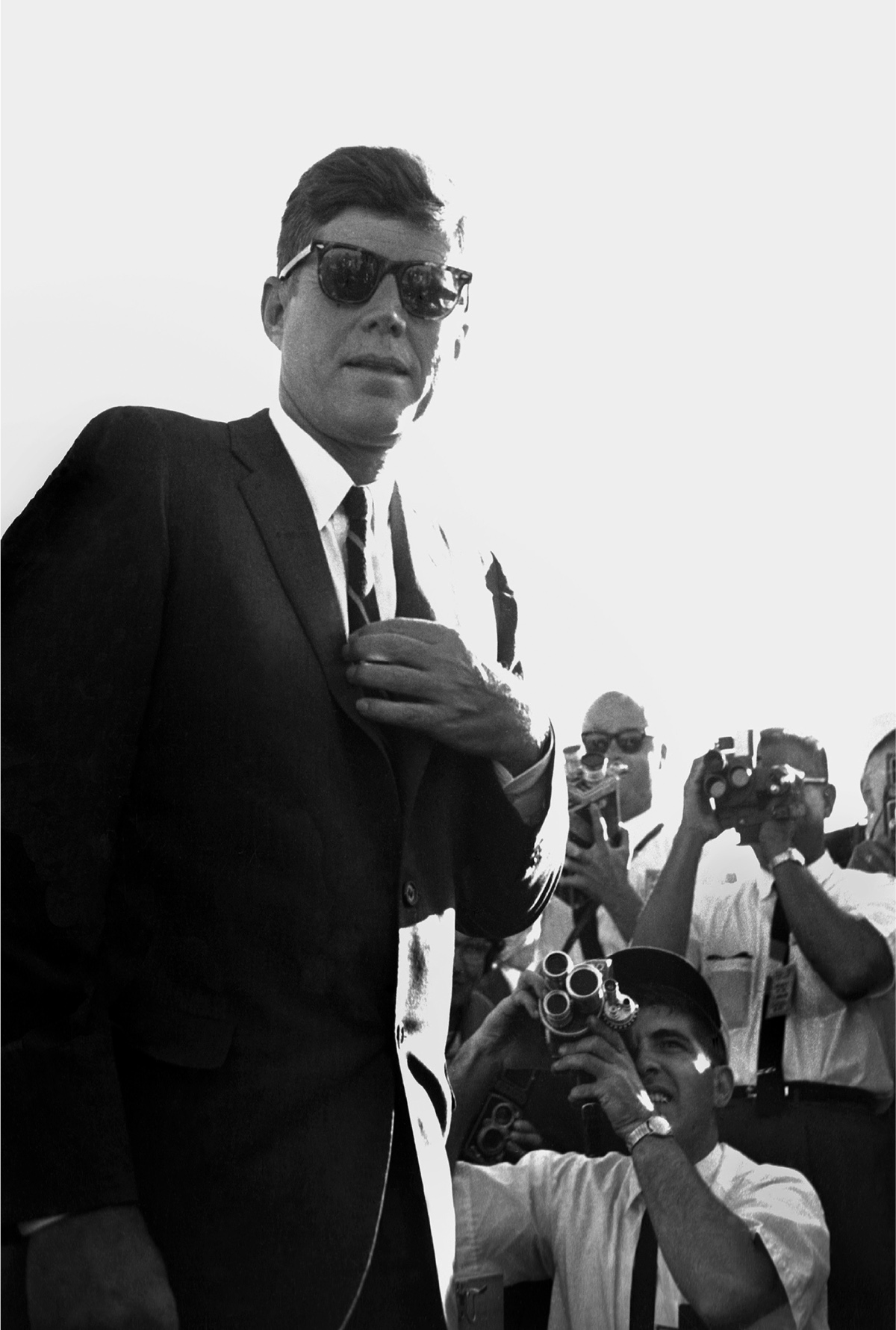

A new era in human history began on July 20, 1969, when Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin Buzz Aldrin walked on the moon. No longer were global citizens shackled to Earth. It was John F. Kennedys vision for an American moonshot that jump-started this epic NASA feat. Photos of moon prints became popular in newspapers around the world.

Buyenlarge/Archive Photos/Getty Images

TO MY COLLEAGUES AT RICE UNIVERSITY AND

TO MY BELOVED WIFE, ANNE

The most difficult thing is the decision to act. The rest is merely tenacity.

AMELIA EARHART

It will not be one man going to the moon... it will be an entire nation. For all of us must work to put him there.

PRESIDENT JOHN F. KENNEDY, MAY 25, 1961

Even the White House ushers were abuzz on the morning of October 10, 1963, because President John F. Kennedy was honoring the Mercury Sevenastronauts Lieutenant Scott Carpenter (USN), Captain Leroy Gordo Cooper (USAF), Lieutenant Colonel John Glenn (USMC), Captain Virgil Gus Grissom (USAF), Lieutenant Commander Walter Wally Schirra (USN), Lieutenant Alan Shepard (USN), and Captain Donald Deke Slayton (USAF)with the coveted Collier Trophy that afternoon in a Rose Garden affair. (Robert J. Collier had been an editor of Colliers Weekly in the early twentieth century; he promoted the careers of Orville and Wilbur Wright, believing deeply that flight was going to revolutionize transportation.) The trophy had been established in 1911 to be presented annually for the greatest achievement in aeronautics in America, with a bent toward military aviation. At the Mercury ceremony were representatives from such Project Mercury aerospace contractors as McDonnell Aircraft Corporation (designers of the capsule) and Chrysler Corporation (which fabricated the Redstone rockets for the U.S. Armys missile team in Huntsville, Alabama). Kennedy wanted to personally congratulate the Magnificent Seven astronauts, all household names, for their intrepid service to the country. And his remarks marked the end of the Mercury projects after six successful space missions.

At the formal ceremony, Kennedy, in a fun-loving, jaunty mood, full of gregariousness and humor, presented the flyboy legends with the prize. It was the first occasion for all seven spacemen and their wives to be together at the White House since the maiden astronaut, Alan Shepard, accepted a Distinguished Service Award for his Mercury suborbital flight of fifteen minutes to an altitude of 116.5 miles on May 5, 1961. Surrounding Kennedy as he spoke were such aviation history dignitaries as Jimmy Doolittle, Jackie Cochran, and Hugh Dryden. Instead of recounting the Mercury Sevens space exploits in rote fashion, Kennedy used the opportunity to drive home his brazen pledge of 1961, that the United States would place an astronaut on the moon by the decades end. Scoffing at critics of Project Apollo (NASAs moonshot program) as being as thickheaded as those fools who laughed at the Wright brothers in 1903 before the Kitty Hawk flights, he turned visionary. Some of us may dimly perceive where we are going and may not feel this is of the greatest prestige to us, Kennedy said. I am confident that its significance, its uses and benefits will become as obvious as the Sputnik satellite is to us, as the airplane is to us. I hope this award, which in effect closes out the particular phase of the program, will be a stimulus to them and to the other astronauts who will carry our flag to the moon and perhaps someday, beyond.

For Kennedy, much depended on the United States going to the moon, beating the Soviet Union, being first, winning the Cold War in the name of democracy and freedom, and planting the American flag on the lunar surface. Just five weeks later, Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas. Writing the presidents obituary in Aviation Week & Space Technology on December 2, 1963, editor Robert Hotz, who had been at the Collier Trophy ceremony that October, predicted that when a NASA astronaut walked on the moon in less than six years time, Kennedy, Americas thirty-fifth president, would be honored as a spacefaring seer whose eternal marching command to his fellow countrymen was Forward!

Even though Kennedy wasnt alive for the fulfillment of his May 25, 1961, pledge to a joint session of Congress to land a man on the moon and return him safely to Earth, the marvel of television made it possible for more than a half-billion people to watch the historic Apollo 11 mission in real time, and I was one of them. On July 20, 1969, when Neil Armstrong gingerly descended from the spider-like lunar module the Eagle with his hefty backpack and bulky space suit, becoming the first human on the moon, I cheered like a banshee. I was only eight years old that summer, and watching all things Apollo 11from the nearly two-hundred-hour galactic journey out of the Space Coast of Florida to splashdown in the Pacific Oceanbecame my obsession. I didnt miss a moment of the long, nerve-racking chain of events that led to the Eagle establishing the moon base Sea of Tranquility (named in advance by Armstrong). I vividly remember our astronauts planting the American flag on the lunarscape, bouncing on the desolate moons surface, handling instruments, and procuring moon rocks.

My family lived in Perrysburg, Ohio, and we considered Armstrong, from the nearby community of Wapakoneta, essentially a hometown boy. It was stunning that this local kid, who grew up on an Auglaize County farm with no electricity, was leading America into the new world of lunar exploration. When Armstrong said, Thats one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind, every member of my family was awed at the instantaneous greatness of it all. We were hardly alone in realizing that Apollo 11 had changed all who watched it unfold or lived in its wake. I was proud of my country.

For years I longed to hear Neil Armstrong describe what it was like to contemplate Earth from 238,900 miles away, to explain, in his own words, the thermodynamics affecting motion through the atmosphere both in launching and reentry. Former Johnson Space Center director George Abbey of Houston (now a colleague of mine at Rice University) once told me that many NASA astronauts felt that looking at Earth was akin to a religious experience. Did Armstrong agree? What did it feel like, emotionally, spiritually, to stand on the surface of the moon? Armstrongs reticence was legendary. He was known to be media shy. But I hoped to persuade him to talk with me about his storied career. Perhaps I could get him to reflect in fresh ways on his lunar experience. In 1993, I wrote him requesting an interview (enclosing signed copies of my books Dean Acheson: The Cold War Years and Driven Patriot: The Life and Times of James Forrestal). I got a polite postcard rejection of the Not now, but Ill keep you in mind variety.

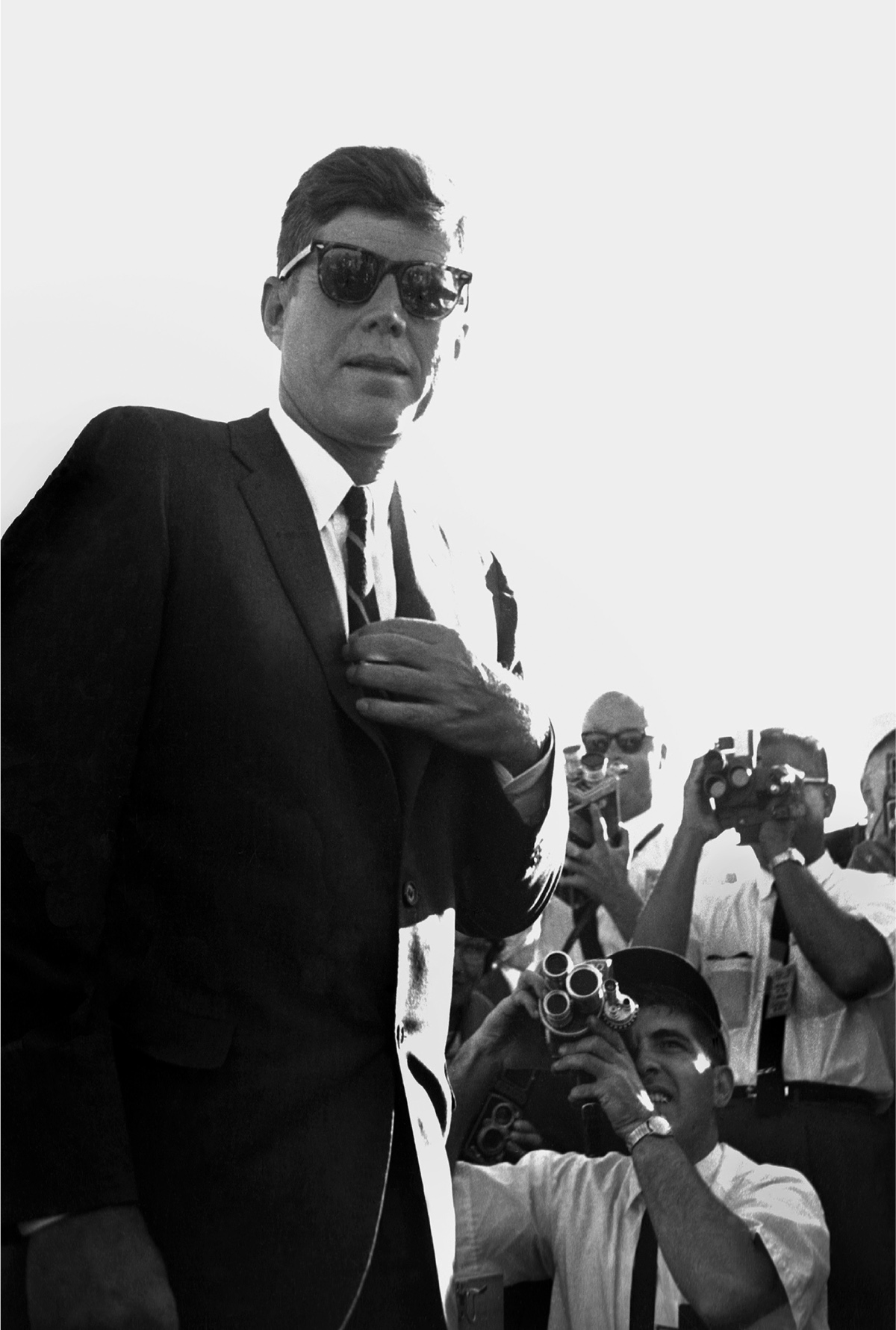

John F. Kennedy was handsome, debonair, and press savvy. Often, when he visited Cape Canaveral, Florida, or Huntsville, Alabama, or Houston, Texas, to inspect NASA sites, he wore dark sunglasses, which gave the visits a touch of Hollywood glamour. Because he was six feet one in height, sitting in a cramped Mercury, Gemini, or Apollo capsule for a photo op was not an option. So he mastered the art of looking upward at rockets.

I. C. Rapoport/Archive Photos/Getty Images

It wasnt until eight years later that NASA afforded me the privilege of interviewing Neil Armstrong for its official Oral History Project. I was surprised at and honored by the chance to speak in depth with the First Manand thrilled when the date was set for September 19, 2001, in Clear Lake City, Texas. Then, eight days in advance of the big meeting, I saw the horrifying collapse of the World Trade Center towers on TV and listened to accounts of the two other disastrous airplane hijackings. A pervasive sense of gloom and urgency enveloped America. Like everyone else, I felt shock and repugnance at the ghastly scenes of our nation under attack, feelings that still burn to this day. I was sure my Armstrong interview would be canceled. But it didnt play out that way. To my utter astonishment, a NASA director telephoned me to say that Armstrong, no matter what, never missed a scheduled appointment. His effort to keep his word was legendary. The post-9/11 skies were largely shut to commercial aircraft, but Armstrong, whose own boyhood hero was flier Charles Lindbergh, refused to cancel his appointment at the Johnson Space Center, piloting his own plane from his adopted hometown of Cincinnati. It was a matter of honor, part of Armstrongs onward code.