FATAL

POLITICS

University of Virginia Press

2015 by the Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia, Miller Center

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

First published 2015

ISBN 978-0-8139-3802-8 (cloth)

ISBN 978-0-8139-3803-5 (e-book)

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress.

Read and listen to the presidential conversations online at www.fatal-politics.org

To Kenneth J. Hughes Sr., Private, US Army

and Maryann Hughes

And let all sleep; while to my shame I see

The imminent death of twenty thousand men

That for a fantasy and trick of fame

Go to their graves like beds

WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, HAMLET

Will it make it easier on you

Now you got someone to blame?

U2, ONE

CONTENTS

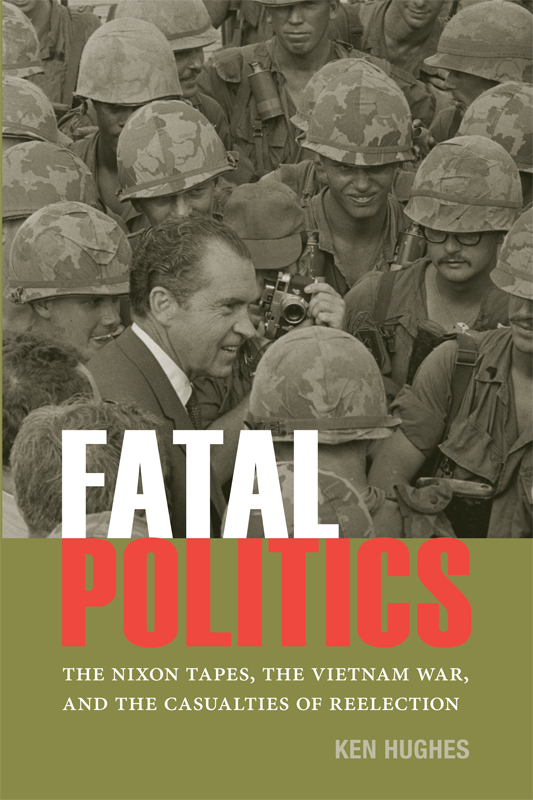

No event in American history is more misunderstood than the Vietnam War. No one did more to keep it that way than the author of the preceding sentence, Richard Milhous Nixon. Its the opening line of his 1985 best seller, No More Vietnams . In the battle over history, however, Nixon had a crucial advantage over his critics. They didnt have access to the best evidence: the classified record of Nixons foreign policy making, especially his secretly recorded White House tapes. The tapes covered the critical periodFebruary 16, 1971, to July 12, 1973when Nixon withdrew the last American troops from Vietnam, negotiated a settlement of the war with North Vietnams Communist government, engineered the diplomatic opening to China, established a dtente with Russia, and won a landslide reelection. The tapes reveal the complex and subtle interplay between all these actionsincluding the ways Nixon manipulated geopolitical events for domestic political gain. Unsurprisingly, he fought until his death in 1994 to keep the American people from hearing the tapes; tragically, it took the federal government nearly two decades, until 2013, to finish declassifying these invaluable and (thanks to Nixons sound-activated recording system) comprehensive historical records. By then it was almost too late. Politicians, policy makers, and pundits now routinely invoke Nixons backstabbing myth as reason to block attempts to end Americas twenty-first-century wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. They even promote Nixon-era strategy as a path to victory in both these countries.

Nixons tapes reveal, however, that he merely came up with a politically acceptable substitute for victory. Neither Nixon nor any of his military or civilian advisers ever devised a workable strategy to win the war, but Nixon and National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger devised a brilliant, if ruthless, strategy to win the election. As Nixon and Kissinger saw it, victory in the presidential election did not depend on victory in Vietnam; they merely had to postponenot preventthe Communist takeover of South Vietnam until sometime after November 1972. To accomplish this end, Nixon kept American soldiers in Vietnam into the fourth year of his presidency, at the cost of thousands of American lives.

That was the military side of his secret strategy. Like his official, publicly announced strategy, Nixons secret strategy had both a military and a diplomatic side. Officially, Nixons strategy was Vietnamization and negotiation. Publicly, Nixon said Vietnamization would train and equip the South Vietnamese to defend themselves without the need for American troops. Secretly, Nixon used Vietnamization as an excuse to prolong the war long enough to delay South Vietnams fall past Election Day 1972.

As for the diplomatic side, Nixon said publicly that the aim of negotiations was to reach an agreement with the North guaranteeing the Souths right to choose its government by free elections. Secretly, however, he did not require the North to abandon its goal of military conquest of the South. Instead, he settled for a decent intervala period of a year or twobetween his final withdrawal of American troops and the Communists final takeover of South Vietnam. For Nixon to completely evade the blame for defeat, he had to do more than prop up the Saigon government through 1972. If it fell shortly after he brought the troops home, Americans would see that their soldiers had died in vain, and Nixon would go down in history as the first president to lose a war. Nixon could avoid this fate, however, if the Communists gave him a decent interval.

Nixon and Kissingers secret strategy, though clearly immoral, did not spring simply from the character flaws of two men. excuse what Nixon and Kissinger did; it merely shows that they acted on the basis of rational political calculation.

Just as important as how Nixon won the 1972 election is how his opponent lost. According to the Emory University professor Drew Westen, political campaigns are built, in part, on the story your opponent is telling about himself and the story you are telling about your opponent. The story Nixon told about himselfthat he would keep the war going only until South Vietnam could defend itself or the North agreed to let it choose its government by free electionswas not true. Unfortunately, the story his opponent told about him wasnt true, either.

The Democratic presidential nominee, Sen. George McGovern of South Dakota, did not accuse Nixon of prolonging the war and faking peace for political gain, of putting his reelection campaign above the lives of American soldiers, of sacrificing them for a fig leaf behind which he would secretly surrender the South to the Communists. Instead, McGovern and other liberals claimed that Nixon would never allow Saigon to fall, that a vote to reelect the president was a vote for four more years of war. Although Nixons tapes show that he was not the steadfast ally of Saigon that he pretended to be, McGoverns charges counterproductively reinforced the image that Nixon had carefully cultivated.

Worse, McGovern didnt know what to do in October 1972 when South Vietnamese president Nguyen Van Thieu publicly declared that the deal Nixon and Kissinger made with North Vietnam was a sellout and surrender to the Communists. The charge was both damning and true, but because it contradicted what McGovern had been saying, he failed to seize the opportunity it offered. Autopsies of McGoverns campaign usually detail his parade of political pratfalls through the summer and fall of 1972, but they neglect its central strategic flaw. Vietnam was the biggest issue of the general election campaign, and McGovern fumbled it.

It didnt have to be that way. Sen. Ted Kennedy, D-Massachusetts, provided an alternative strategy when he accurately accused Nixon of cynically using Vietnamization as a fraudulent cover for timing military withdrawal to his reelection campaign. Kennedys brother-in-law Sargent ShriverMcGoverns running mate in the fall campaignaccurately accused Nixon of negotiating surrender. If McGovern had told that story throughout the campaign, not only would he have been right, but Nixons troop withdrawals and Thieus blowup would have provided the story with credible confirmation. Instead, McGovern and other liberals lost control of the foreign policy narrative, telling a story about Nixon that was both false and flattering to the man it was designed to defeat.

Though the 1972 campaign is decades past, the myth Nixon made (and McGovern unwittingly reinforced) persists, now hallowed as if it were settled history. Right and Left agree that Nixon was determined to use American military power to preserve South Vietnam until Congress tied his hands. The Right calls that losing Vietnam, the Left calls it ending the war, but both agree thats what happened. As we shall see, Nixon invited Congress to pass legislation denying him authority to militarily intervene in Vietnam, despite having the votes he needed to sustain a veto. Legislation barring military intervention throughout Indochina (Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia) passed with a veto-proof majority only after Nixons conservative supporters joined his liberal opponents and accepted his invitation. Like Nixons secret military and diplomatic strategy, this legislative maneuver enabled him to deny responsibility for losing Vietnam.