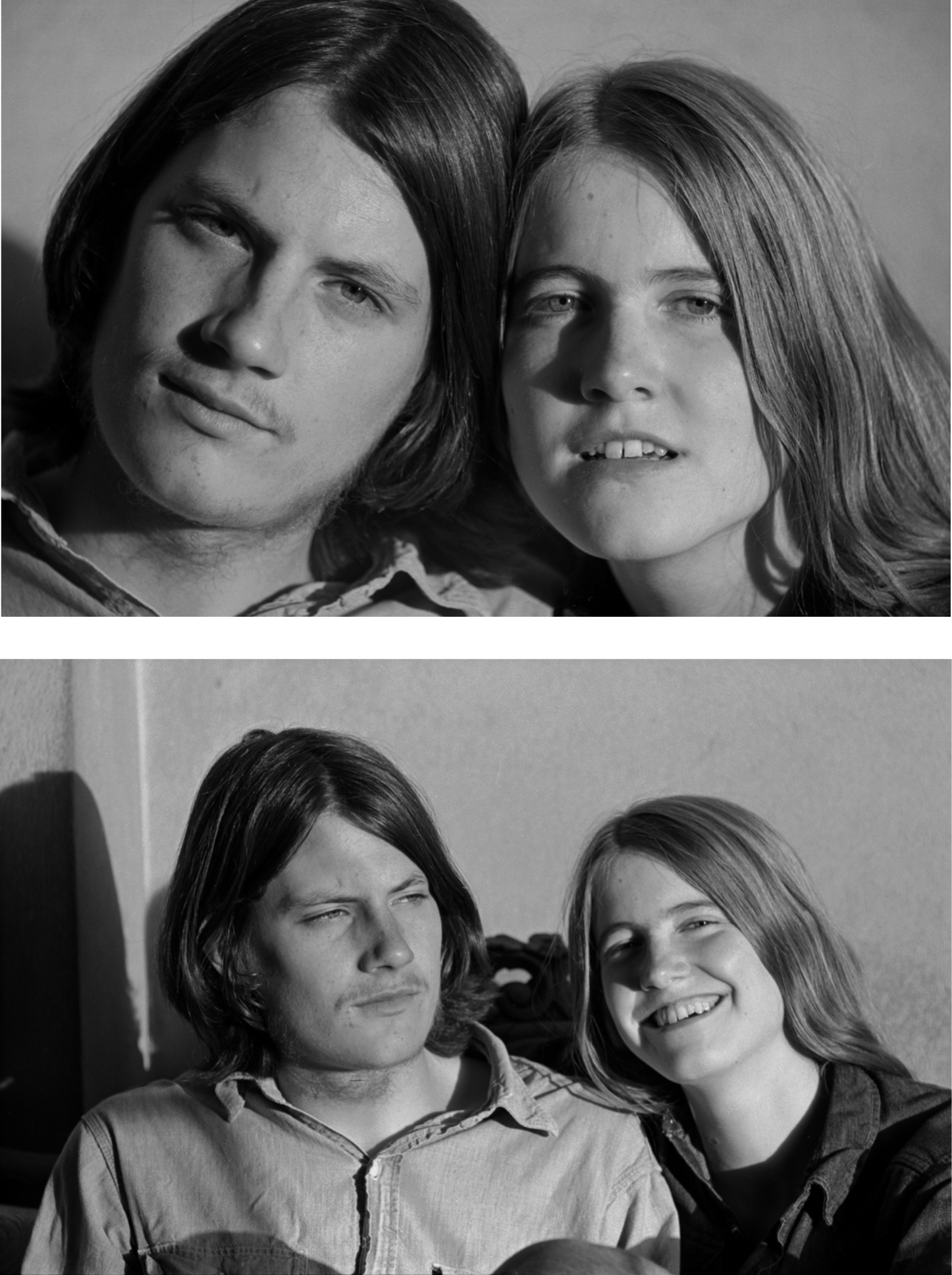

The author, Elizabeth Partridge, and her boyfriend, Warren Franklin, 1968.

PROLOGUE

November 1968

AS SOON AS the hitchhiker climbed into the backseat next to me, I was sorry we had picked him up. Standing by the road in a coat and hat, hed looked like one of usa teenager heading out of town Friday night, away from parents and school. But inches away, he felt tense and vigilant. He reminded me of a cougar, muscles taut, ready to spring.

John and Warren, in front, laughed over a joke as we sped onto the freeway. We were headed for Johns family cabin in the mountains, and we could get the hitchhiker halfway to Reno, Nevada, where he was headed. He adjusted the heavy duffel bag on his lap and pulled off his knit hat. His hair was short. Military short.

Wherere you coming from? asked John, glancing in the rearview mirror. Warren turned around, took one startled look at the hitchhikers short hair, and swung back.

Nam, the hitchhiker said. He looked at us warily, taking in our love beads, and Johns and Warrens long hair.

Nam? asked John.

There was a long pause. Im a Green Beret, the hitchhiker finally said. Been in Vietnam a year.

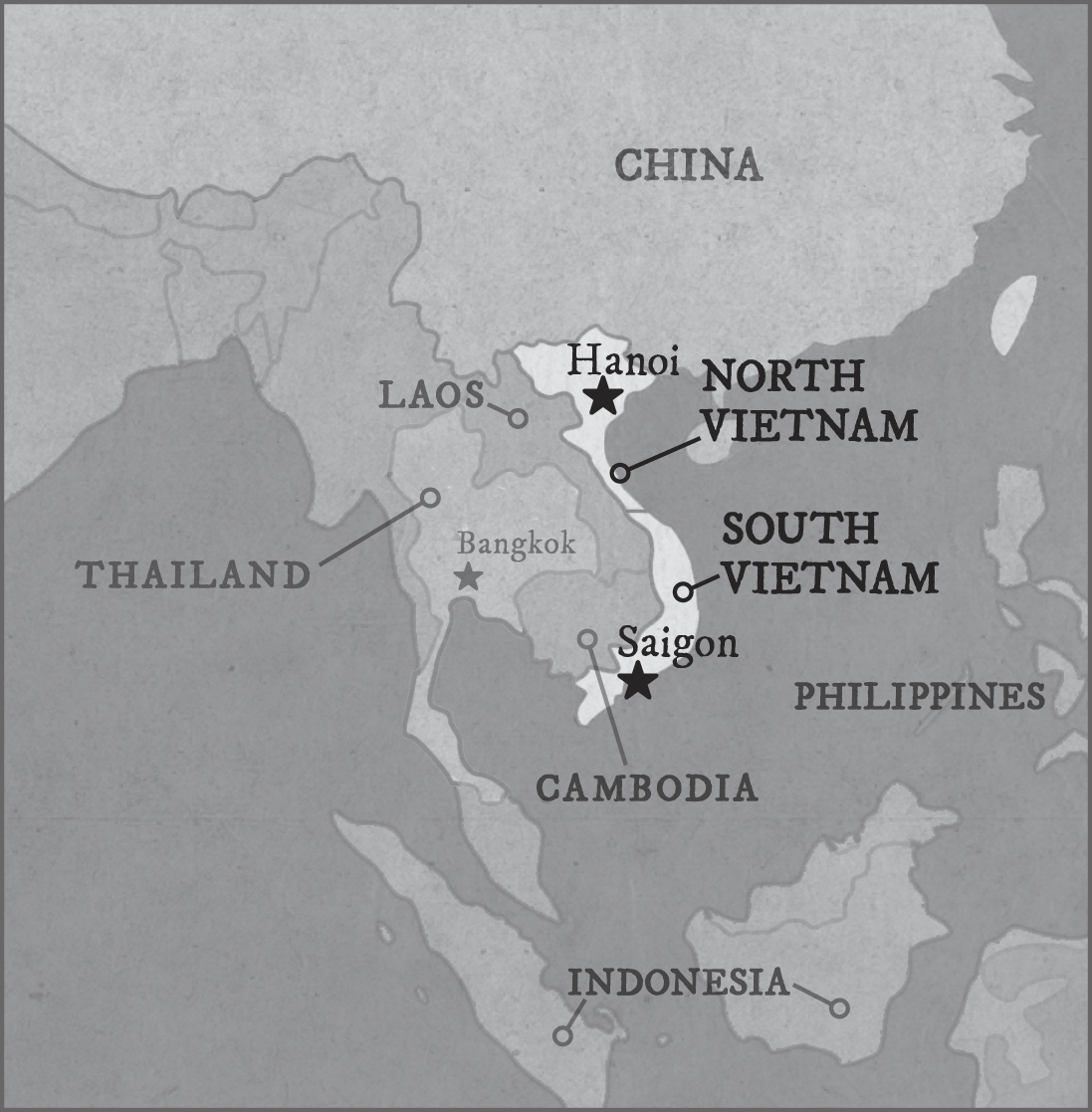

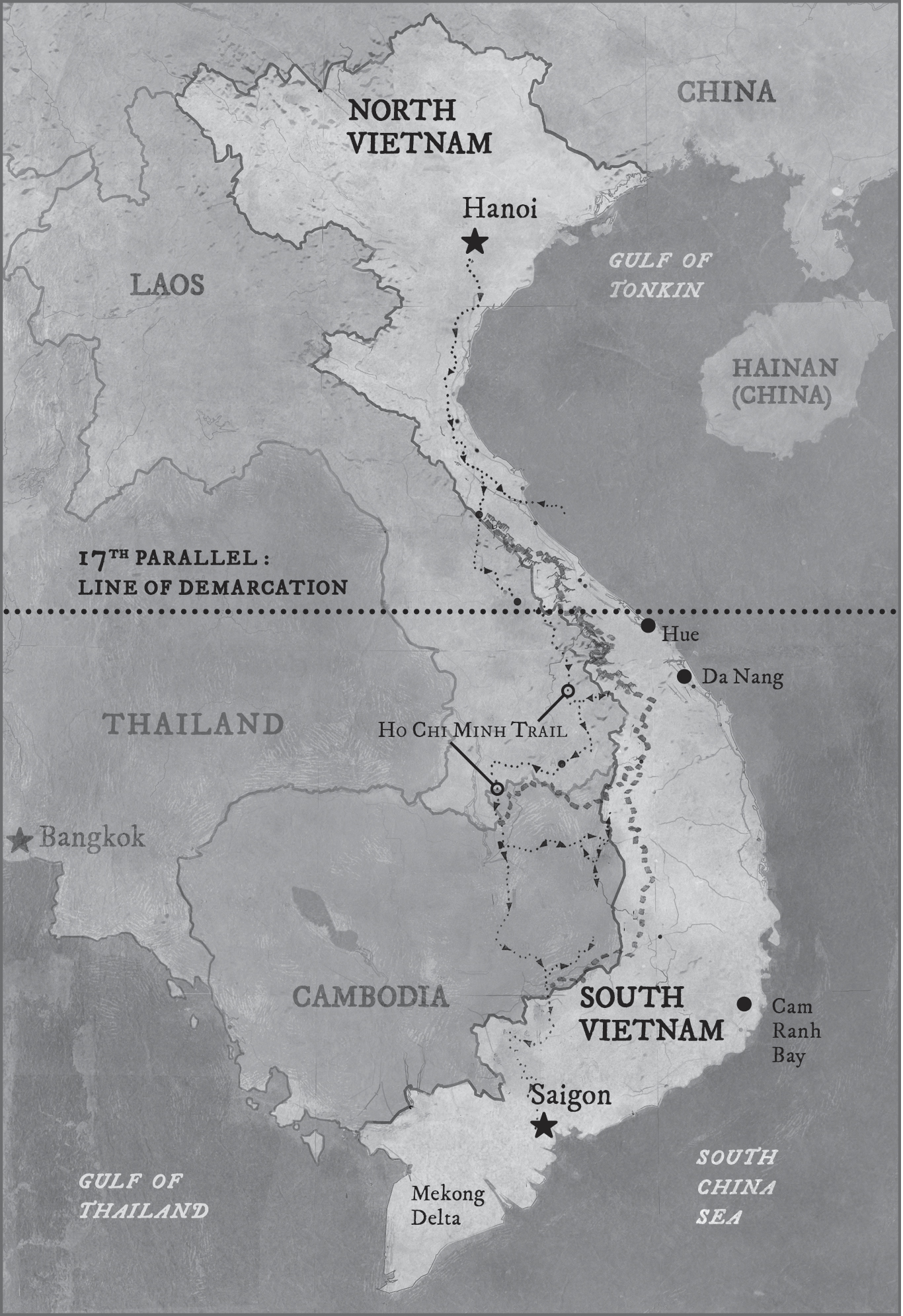

Vietnam. It was like a concussion grenade smashed against the windshield and ricocheted back through the car. The Vietnam War. It was stalking us all. We were high-school seniors, and the clock was ticking: once out of high school all American males faced two years of compulsory military service. When they turned eighteen, men had to register with the Selective Service System, the agency responsible for implementing a draft. With thousands of soldiers being sent to Vietnam, there were not enough volunteers for the military to meet troop needs. We watched anxiously as people we knew were drafted into the army. It didnt matter whether they volunteered or were drafted, if they were ordered to Vietnam, they would be there for twelve months.

Three years earlier, President Lyndon B. Johnson had sent troops to aid the South Vietnamese government in its fight against the Communist North Vietnamese. Every night on the news, we watched footage of battles. The sound of machine-gun fire and exploding bombs reverberated off our living-room walls. Villagers ran from combat clutching small children as news anchors reported ever-growing numbers of Americans killed in action. It was horrible to watch, but impossible not to.

Warren, John, and I went to Berkeley High School, in California. We were in the West Coast epicenter of the military as they shipped men and equipment across the Pacific to Vietnam. The San Francisco Bay Area was a constant flash point for demonstrations and marches against the war. I was a dreamy, bookish girl, not inclined to politics and protest. But the war made me feel desperate, and I wanted it to end. All I could do was join the street protests, add my body to the crowd.

We didnt mix, those of us against the war and the guys who came back from Vietnam. And now I was sitting next to someone just out of Vietnam, fresh from his job to kill or be killed. I pulled away from him, moved closer to my window. What had he seen in Vietnam? What had he done?

It was a long, awkward drive. We didnt ask him any questions, and he volunteered nothing.

When we finally arrived at the cabin, it was past midnight, with a heavy, wet snow falling. We couldnt leave him by the side of the road, and invited him in for the night. He sat in a corner of the kitchen as we made a late meal. He was perfectly still except his eyes, which flicked from the door to the dark windows, to our faces and back to the door. I couldnt shake the feeling that if some perceived danger set him off, he was ready to spring.

He slept on the living-room floor rolled in a blanket. When we woke up in the morning, he was gone.

A National Guard helicopter sprays tear gas on protestors at the University of California, Berkeley, 1969.

AFTER GRADUATION, JOHN enrolled in college, which deferred his military service. Warren was ordered by the Selective Service, the agency in charge of the draft, to report for his physical. He was given a medical deferment for the braces he wore on his teeth, and told to report back in a year. I started college at nearby UC Berkeley, where my life was a mixture of antiwar rallies and marches and beginning French and rhetoric classes. Men were still being drafted, and Americans and Vietnamese were dying. Why couldnt weor wouldnt weget out of Vietnam?