Minority Soldiers Fighting in the Vietnam War

ELIZABETH SCHMERMUND

Published in 2018 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC

243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016

Copyright 2018 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC

First Edition

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the prior permission of the copyright owner. Request for permission should be addressed to Permissions, Cavendish Square Publishing, 243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016. Tel (877) 980-4450; fax (877) 980-4454.

Website: cavendishsq.com

This publication represents the opinions and views of the author based on his or her personal experience, knowledge, and research. The information in this book serves as a general guide only. The author and publisher have used their best efforts in preparing this book and disclaim liability rising directly or indirectly from the use and application of this book.

CPSIA Compliance Information: Batch #CS17CSQ

All websites were available and accurate when this book was sent to press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Schmermund, Elizabeth.

Title: Minority soldiers fighting in the Vietnam War / Elizabeth Schmermund.

Description: New York : Cavendish Square, 2018. | Series: Fighting for their country: minorities at war | Includes index.

Identifiers: ISBN 9781502626660 (library bound) | ISBN 9781502626608 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Vietnam War, 1961-1975--African Americans--Juvenile literature.

Classification: LCC DS559.8.B55 S34 2018 | DDC 959.70434--dc23

Editorial Director: David McNamara

Editor: Caitlyn Miller

Copy Editor: Alex Tessman

Associate Art Director: Amy Greenan

Designer: Stephanie Flecha

Production Coordinator: Karol Szymczuk

Photo Research: J8 Media

The photographs in this book are used by permission and through the courtesy of:

Cover Co Rentmeester/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images; Brian Wickham/Wikimedia Commons/File:BG Charles J. Girard arrives in Saigon, March, 1969.jpg/Used with Permission.

Printed in the United States of America

Protesters gather to make their voices heard against the Vietnam War.

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

A Controversial War

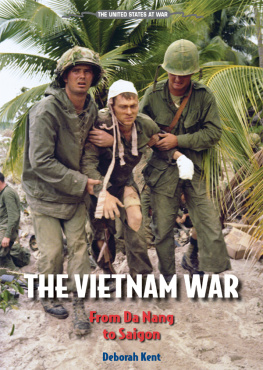

T oday, the Vietnam War is often regarded as a dark period in American history. The United States entered the war when Vietnam was divided into two separate countries: North Vietnam and South Vietnam. North Vietnam was controlled by a communist government and was supported by communist nations, including the Soviet Union , while South Vietnam was anti-communist and was supported by democratic countries, including the United States. Beginning in November 1955, the war lasted nearly twenty years before ending on April 30, 1975. When entering the war, United States government officials never imagined that it would last so long. They also had no idea that it would cause such great destruction, both on the warfront and on the home front, with American confidence in the US government diminishing. During this drawn out and eventually unsuccessful war, 58,193 Americans were killed and over 150,000 were wounded. In addition, the war was very unpopular because of the style of fighting called guerilla warfare that was used in the war. Troops were ambushed with booby traps and fighters in disguise. Adding to the wars unpopularity, the United States began a draft to send young men into combat.

A draft is when a government forces certain citizens usually through a lottery, or a random selectionto fight in a war. The Vietnam War draft began in 1969 and lasted until 1973. Many people did not believe in the wars cause and, thus, did not want to fight. But if they were chosen for the draft, they had to go. Approximately 2,215,000 men were drafted into military service during the period between 1964 and 1973. Many thousands also attempted to evade the draft and went into hiding. About 30,000 men went to Canada during this period so that they would not be drafted.

The draft disproportionately affected poor, working-class, and minority young men. Approximately 55 percent of American forces in Vietnam came from a working-class background, while 25 percent came from poorer socioeconomic backgrounds. The war also disproportionately affected minority soldiers. While, at the time, African American men made up approximately 11 percent of the American population, nearly 13 percent of soldiers in the Vietnam War were African American. When it comes to fatalities, nearly 20 percent of all casualties during the height of the Vietnam War from 1965 to 1969 were black soldiers (25 percent in 1965). Due to this inequality, then-president Johnson ordered that the participation of African American soldiers should be cut in combat units. This effectively cut the casualty rate of black soldiers from 20 percent to less than 12 percent by 1969.

While the US government did not keep statistics of the number of Hispanic soldiers fighting in the war, subsequent analysis shows that they made up approximately 5.5 percent of all casualties during the war. This points to the fact that Hispanics were also overrepresented in casualties than in the general population, where they made up less than 5 percent of the population.

Due both to these inequities and to the general belief among Americans that Vietnam was a lost cause and one that American soldiers should not die for, many Americans protested the draft. Beginning in 1964, students would burn their draft cards in resistance of the war. They wrote to representatives and organized mass protests. In the last years of the war, there were many draft resisters. These people refused to serve on moral grounds. In 1972, there were more conscientious objectors than people called to serve. Overall, over 200,000 people were categorized as delinquent, or they had not served although they had been drafted, throughout the war. Due to the conflicting beliefs of the American public, returning soldiers were often treated with disdain upon arriving back in the United States. They would be spit on or taunted and often did not receive public recognition for their service.

In addition to general public perception, African American soldiers experienced prejudice in the militaryand also could feel more resentful at being compelled to serve for a country in which they were not even granted full rights due to their race. In 1966, President Johnson began a program called Project 100,000, which lowered the qualification standards for men to be drafted into the war. Previously, many African Americans who had perhaps not had a full education had been able to avoid the draft. However, with this program, they were no longer able to do so. Between 1966 and 1969, 41 percent of those drafted through this program were African Americans. Poor men and Hispanic men were also more likely to be drafted under this program.

Despite the public reception at home, many minority soldiers were highly decorated and well trained. Approximately twenty African American soldiers received the Medal of Honor for their service in Vietnam, which is the highest military honor given. Several African Americans were promoted to general, the highest rank in the army. Following the Vietnam War, African Americans made up an even higher percentage of the American military than previously. By 1976, they made up more than 15 percent of all those in the American military. However, proportionally, they remained underrepresented in the higher ranks; African American officers continued to account for less than 4 percent of all military officers.

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION