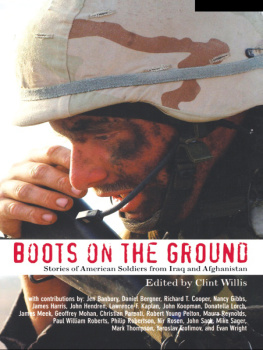

T hese pages include 22 attempts to describe the experiences of I American soldiers in Afghanistan and Iraq during recent years. I Those experiences are not easy to uncover, in part because few soldiers are yet in a position to write or to speak openly about their life in these wars. That will come later; it always does. Meanwhile, most of the work at hand is written by journalists and other camp followers.

That said, many of these witnesses share at least some of the risks and indignities these wars inflict upon the soldiers who fight them. Journalists have suffered casualties in Afghanistan and Iraq, and the work featured in these pages suggests that some writers who survive their exposure to these wars are permanently marked by what they have seen.

Some of these writers have taken up the task of trying to understand and describe the experiences of the mostly young Americans who must fight these new wars. That experience is more interesting than the romanticized and sentimental reports that dominate some popular media outlets. Such reporting distorts and exploits the experience of the young soldiers it pretends to honor.

The reports in this book offer a more complex mosaic. The mosaic isnt a pretty one: American soldiers are competent by some standards; they also make terrible mistakes, sometimes killing each other or harmless civilians. Some American soldiers are compassionate and open-minded; others are narrow and cruel. Many American soldiers badly want to believe that they are doing the right thing, and some do believe it; others are angry or skeptical about their mission. Some American soldiers are brave and selfless; others are not. Their sentiments include some that you wont hear on the Fox network: Imscared. Get me out of this place. Why are we here?

Similar sentiments echo down the halls of our recent history, from other American wars. Each war has had its criticsno exceptionsand so do American incursions into Afghanistan and Iraq. Some writers who have contributed work to this collection are strong critics of our recent wars; most keep their distance from such questions. All of these writers offer valuable and often moving glimpses of what life is like for the men and women who must try to implement our countrys military policies at the beginning of the 21st century.

Bumper stickers and editorialists urge us to support our troops. We cant begin to do so without trying to understand and acknowledge the complex and grueling nature of their experience.

The Marine

by Mike Sager

Mike Sagers piece about Lieutenant Colonel Robert Sinclair and his Marines appeared in Esquire (December 2001).

D ragon Six is Oscar Mike, on the move to link up with Bandit. Foot mobile along Axis Kim, he is leading a detachment of ten U.S. Marines across a stretch of desert scrub in the notional, oil-rich nation of Blueland. He walks at a steady rate of three klicks per hour, three kilometers, muscle memory after twenty-three years of similar forced humps through the toolies, his small powerful body canted slightly forward, his ankles and knees a little sore, his dusty black Danner combat boots, size 8, crunching over branches and rocks and coarse sand.

His pale-blue eyes are bloodshot from lack of sleep. His face is camouflaged with stripes and splotches of greasepaintgreen, brown, and black to match his woodland-style utilities, fifty-six dollars a set, worn in the field without skivvies underneath, a personal wardrobe preference known as going commando. Atop his Kevlar helmet rides a pair of goggles sheathed in an old sock. Around his neck hangs a heavy pair of rubberized binoculars. From his left hip dangles an olive-drab pouch. With every step, the pouch swings and hits his thigh, adding another faint, percussive thunk to the quiet symphony of his gear, the total weight of which is not taught and seldom discussed. Inside the pouch is a gas mask for NBC attacksnuclear, biological, or chemical weapons. Following an attack, when field gauges show the air to be safe once again for breathing, regulations call for the senior marine to choose one man to remove his mask and hood. After ten minutes, if the man shows no ill effects, the rest of the marines can begin removing theirs.

The temperature is 82 degrees. The air is thick and humid. Sounds of distant fire travel on the wan breeze: the boom and rumble of artillery, the pop and crackle of small arms. He is leading his men in a northwesterly direction, headed for an unimproved road designated Phase Line Rich. There, he will rendezvous with Bravo Company, radio call sign Bandit, one of five companies under his command, nearly nine hundred men, armed with weapons ranging from M16A2 rifles to Humvee-mounted TOW missile launchers. In his gloved right hand he carries a map case fashioned from cardboard and duct tapethe cardboard scavenged from a box of MREs, meals ready-to-eat, high-tech field rations that cook themselves when water is added. Clipped to the map case is a rainbow assortment of felt-tip pens, the colors oddly garish against the setting. His 9mm Beretta side arm is worn just beneath his right chest, high on his abdomen. The holster is secured onto his H harness, a pair of mesh suspenders anchored to the war belt around his waistwhich itself holds magazine pouches with spare ammo and twin canteens. Altogether, this load-bearing apparatus is known as deuce gear, as in U.S. Government Form No. 782, the receipt a marine was once required to sign upon issuance. These days, the corps is computerized.

Near his left clavicle, also secured to his H harnesswhich is worn atop his flak vestis another small pouch. Inside he keeps his Leatherman utility tool, his government-issue New Testament, a bag of Skittles left over from an MRE, and a tin of Copenhagen snuff, a medium-sized dip of which is evident at this moment in the bulge of his bottom lip, oddly pink in contrast to his thick camo makeup, and in the bottom lips of most of the men in his detachment, a forward-command element known as the Jump. They march slue-footed in a double-file formation through California sage and coyote bush and fennel, the smell pungent and spicy, like something roasting in a gourmet oven, each man silent and serious, deliberate in movement, eyes tracking left and right, as trained, each man taking a moment now and then, without breaking stride, to purse his lips and spit a stream of brownish liquid onto the ground, the varied styles of their expectorations somehow befitting, a metaphor for each personality, a metaphor, seemingly, for the Marine Corps itself: a tribe of like minds in different bodies, a range of shapes and sizes and colors, all wearing the same haircut and uniform, all hewing to the same standards and customs, yet still a collection of individuals, each with his own particular style of spitting tobacco juice, each with his own particular life to give for his country.

![Willis - Beer: a cookbook: good food made better with beer: [recipes]](/uploads/posts/book/224368/thumbs/willis-beer-a-cookbook-good-food-made-better.jpg)