To my parents,

Maida and Robert Greenberg

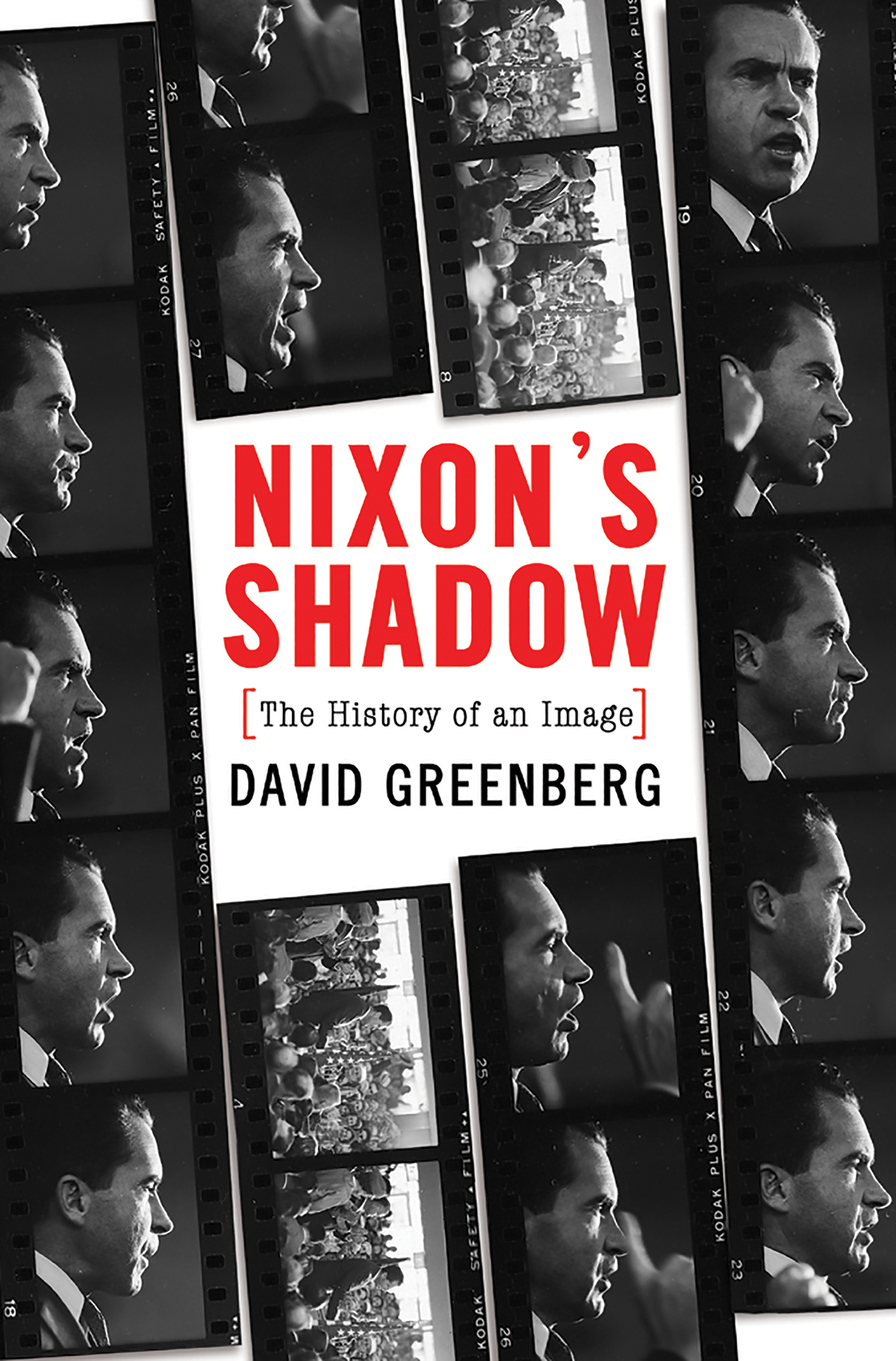

NIXONS

SHADOW

Do you remember/Your president Nixon?

David Bowie

Shortly after Nixons death in 1994, a security guard at the Nixon Library witnessed a series of unusual phenomena, according to the L.A. Weekly. One night he saw a phosphorescent green cloud floating above Nixons headstone. Another night he observed a figure entering the old Nixon clapboard house, which is preserved on the grounds, only to find the doors locked when he inspected it. On other occasions he would hear knocking noises coming from the museums Watergate exhibit, and the next day the machines that play the White House tapes wouldnt be working right. Some visitors also claimed to have seen what might have been Nixons ghost in their peripheral view, or to have felt a sudden chill while strolling the grounds. The L.A. Weekly journalist was himself dubious about these purported instantiations of Nixons shadow, but he noted that Oliver Stone has based movies on less. And he recalled a comment that Nixon had made to Newsweek in 1986: They see me and they think, Hes come back, or Hes risen from the dead.

Nixons gift for resurrecting himself, for staging comebackslike a phoenix, it was said, or Lazarus, or Draculawas evident throughout his career. The alleged ghost-sightings merited mention in an alternative paper only because a lighthearted reporter appreciated them as a literalization The reference to Elvis Presley was apt: The King, like the president, enjoyed a reputation as a comeback artist nonpareil, and in his case too the idea was made literal after his death in the form of imagined glimpses of his ghost.

Perhaps it was more than a cultural oddity that the most requested Nixon items from the National Archivesand the best-selling Nixon image at the Nixon Library and in souvenir shops elsewherewere those bearing photographic images of Nixon and Elvis together on the occasion of the rock stars self-arranged visit to the White House in December 1970. The pictures taken at the meeting appeared on T-shirts, ashtrays, screen-savers, and the like, and even inspired a small corpus of bad art, including a novel and a made-for-cable-TV movie. Those attempts to imagine a narrative behind the meeting fell flat because they stood no chance of improving on the deliciously bizarre image itself: The two men awkwardly facing the camera, a row of five drooping flags arrayed behind them like synthetic Christmas trees. Nixon is wearing an American flag pin in his lapel, Elvis an enormous gold belt buckle that makes him look like a professional wrestling champion. They are clasping hands firmly, forming a bond. They could be wax replicas wheeled over from Madame Tussauds.

To the culturally attuned liberal cognoscenti, the photographs appeal lay in its hilarious incongruity: the epitome of Republican squareness forcing a smile with a bloated, over-the-hill, and quite possibly stoned rock star who was petitioning the president to join the war on drugs. For them, the image was a classic of irony, the two men taking seriously a moment that later generations would view with detached amusement. But such attitudes toward the picture cant account for its popularity. Other Americansheirs to the Silent Majority who voted for Nixon in 1972 and who made Elviss 1968 comeback concert a smash successliked the picture, too. They saw in it two admirable, even great men fortuitously thrown together. The irony, for them, was that there was no irony.

Yet there was a third option besides viewing the photograph condescendingly or viewing it reverentially. Though mass-produced and badly appropriated, the image itself was more than kitsch. For all their surface ridiculousness, the late-career Elvis and the early-1970s Nixon (as seen from a post-Watergate vantage point) both exuded a certain stature. Just as Elvis, however pathetic, still mattered to anyone who cared about rock n roll, so Nixon, for all his disgrace, insisted on mattering to anyone who cared about politics. Loved or hated, Nixon had made a difference. He had to be reckoned with.

At Nixons funeral on April 27, 1994, in Yorba Linda, California, President Bill Clinton stood on the dais with Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, and George Bushthe four other men who had succeeded Nixon in the nations highest office. Before a crowd that included Gordon Liddy and George McGovern, before cameras that beamed his speech around the world, Clinton extolled the late president and admonished the reporters, who were every bit as much his own enemies as Nixons: May the day of judging President Nixon on anything less than his entire life and career come to a close.

Like the funeral coverage as a whole, Clintons words were construed as official certification of Nixons last comeback. For the former McGovern campaign worker whose wife served on the Watergate Committees legal team to call for a fairer reassessment of Nixon surely indicated a turn in opinion: that hatreds were fading, passions cooling, more objective assessments imminent. In fact, Clintons words, typically, said less than they appeared to say. Judging Nixonjudging anyoneon less than his entire life and career is inherently unfair. The question of how to judge Nixons life Clinton left unanswered. Fittingly, it remained a matter of contention.

Some eulogists took the occasion to try to rehabilitate Nixon, painting his career as a model of statesmanship: Clinton himself stressed Nixons skill in working his way back into the arena by writing and thinking. Henry Kissinger called his boss one of the seminal presidents in foreign affairs, citing not only dtente and the China opening, but long-forgotten deeds from the creation of the European Security Conference to improved relations with Arab nations. Nixon, too, promoted the statesman image even in death. Thumbing his nose at those who detested him for prolonging Vietnam, he had decreed that his headstone bear as an epitaph a line

The paeans to Nixons diplomacy, however, showed but one of Nixons many faces. For the droves of well-wishers converging on Yorba Lindathe forty thousand citizens who had in recent days braved crackling thunder and pelting hail, bumper-to-bumper freeways and swarming crowds, to pay him tributethe Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty or the European Security Conference mattered little next to Nixons stubborn defense of their conservative values. It wasnt Kissingers sonorous eulogy that moved these legions but Bob Doles lachrymose requiem for Nixon the fighting populist. To tens of millions of his countrymen, Richard Nixon was an American hero, Dole said, before sobbing, a hero who shared and honored their belief in working hard, worshiping God, loving their families and saluting the flag,... truly one of us.

Yet Doles Norman Rockwell image wasnt the end of the story either. In the newspapers, and in the assessments of historians trotted out to comment, a different picture emerged: a man who established agencies to protect the environment and worker safety, who sought to expand welfare, who adopted Keynesian economic policies. A Newsday article entitled Richard Nixons Liberal Legacy suggested that history might yet come to enshrine him in the pantheon of liberal saints, or at least view him with a greater ambivalence than his detractors might ever have imagined.

De mortuis nil nisi bonum, says a Latin proverb: of the dead say nothing unless it is kind. The funeral eulogists, unsurprisingly, omitted or downplayed Watergate. Yet a few guests dared to broach the subject, if only to defend their late leader as the target of runaway liberal wrath. Ben Stein reminisced about the speech he wished Nixon had given in August 1974 instead of resigning: Yes, I made mistakes, Stein imagined a defiant Nixon saying, but I didnt have call girls in the White House and I didnt have Mafia pals.... I didnt build a TV empire completely on peddling influence. Nixons old everyone does it argument still gripped some. He goofed, but I didnt see any halos above anybody elses head then in Washington or around here tonight, said Jim Schiffman, a Southern Californian who came to the funeral.

Next page